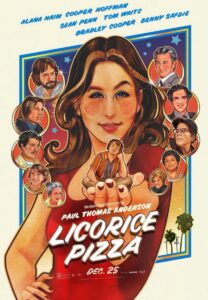

Every now and again, it feels like the critical community will assemble a quorum and make a motion to retire some turn of phrase that has been ground down to the nub. The most recent phrase to become cliched is saying that a film’s place is like an actual character in the film. New York City has been called a character so many times, it’s actually low-key scandalous that all five boroughs have never been nominated for an acting Oscar. I get the need to scale this tired metaphor back due to overuse. It also presents a challenge for me in writing a review of Licorice Pizza, Paul Thomas Anderson’s third film by my count to be immersed in his childhood stomping grounds, the San Fernando Valley. So, true to my word, I will not say that the Valley (Los Angeles’ sprawling, adult film-friendly neighbor to the north) is a character in Anderson’s latest home run. First, because it’s a lazy way of shortcutting what is better to fully describe. The early 1970’s Valley of Licorice Pizza is a richly shot, intricately specific (it feels instantly familiar even for someone like myself who has spent very little time there), entirely lived in part of the world. Its fast food drive ins, sushi bars, grubby convention centers, suburbs, fine dining establishments, high schools, dumpy mattress retailers and municipal golf courses all feel vibrant and down to earth at the same time. They are all the fine-tuned product of an artist who has spent a lifetime feeling both love and boredom for these old places. The Valley is not a character but a place in Licorice Pizza, and Anderson just has the visual flair and conceptual imagination to give that place fundamental importance; to render it like its details matter. Secondly, Licorice Pizza has no need of the Valley as a character because, as with any Anderson film, it is already uncommonly rich with actual characters, from its two fantastic leads down to a murderer’s row of phenomenal one-to-two scene roles. Anderson regular John C. Reilly plays Fred “Herman Munster” Gwynne for a literal instant, handily earning himself the honor of 2021’s best 10-second performance. The characters in Licorice Pizza are like characters and the Valley is like (like) a place, and both of those elements have been brought to the screen by one of the seminal talents of the last thirty years. I hope this brief foray into place as character, character as place, and each thing as itself hasn’t been too disorienting. But if it has been, I hope you’ll forgive it in this case, seeing as blissful disorientation is one of Licorice Pizza‘s prominent virtues.

Licorice Pizza is an early 1970’s coming of age love story (though whether we should root for it to become a love story is up for debate), set in the aforementioned Valley. A 15-year old named Gary Valentine (Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s dead ringer of a son Cooper Hoffman, making a terrific debut) already feels too big for the walls of his high school. Gary has a lot of natural confidence from years of being a child star. His mother’s public relations company has made its name on marketing him until very recently. The acting gigs, even the commercial work, have sadly disappeared since his height shot up and his voice cratered. Nonetheless, Gary has the easy, cocksure cool of a kid who has spent most of his life being the family’s major breadwinner. A born hustler. A guy who is forever considering the angles and looking out for the next big score. On the day we meet Gary, his hustle is not a financial opportunity but the attention of a young woman whose ear he is chatting off. Alan Kane (Alana Haim of the rock band HAIM, in her absolutely ferocious debut) is a sardonic 25-year old photography studio employee who is there to help with the school’s photo day. Gary flirts shamelessly, but with the wide-eyed sincerity of a teenager who firmly believes he’ll be the first to knock life out in the first round, if he hasn’t already. Alana, a smart, ambitious 25-year old Jewish woman stuck living claustrophobically at home with her parents and sisters, has none of Gary’s shiny optimism. And she is less than impressed (and even less convinced) by his boasts of former Hollywood stardom. Nevertheless, and despite her visible annoyance with Gary, she ends up meeting him for dinner that night and it isn’t long before she’s accompanying him as a chaperone to a TV reunion special for the Cheaper By the Dozen-esque film franchise he has now clearly aged out of. Their connection is a testy one. He puts on airs. She domineers him and regards him with snarky fatigue. And yet, Gary’s starry-eyed faith that they were meant to know, maybe even love, one another is not entirely off base. Anderson is also wise and subtle to never really endorse their age-inappropriate, not-quite-romantic codependency. He evokes The Graduate in both his empathy for youth adrift and the quiet implication that love maybe shouldn’t conquer all. Licorice Pizza is the complex, but sweetly non-judgmental story of two confused, restless youths who are probably going to end up together one day. And the wrong and the right of that future, and whatever joys and mistakes it might hold, is left for us to weigh. Alana helps Gary start a reasonably profitable waterbed business. Gary introduces Alana to the same Hollywood connections that are no longer of use to him. Alana, the year’s most wonderfully thorny and funny screen creation, takes us through the inner turmoil of a young woman trying to choose a future and finding no obvious path. I have heard Licorice Pizza described as being about Gary in its first half and about Alana in its second half. And, while I think it’s very much a duet between them the whole time, I do also agree that it becomes her story. Because it is about her decision. The tragicomedy of 15-year old Gary Valentine is that he likely already is who he is going to be for the rest of his life: an charmingly oily, impulsive, slightly conceited, but essentially good-hearted hustler. Money and the desire for the next big thing will drive him from scheme to scheme; from waterbeds to pinball arcades to whatever new grift the 1980s might hold for him. In spite of being ten years Gary’s senior, t is Alana who must still decide who she wants to be (the question of who she ends up with representing just a single important piece of that) and where she wants to go.

Like Gregg Mottola’s Adventureland, another splendid coming of age film, Licorice Pizza is about characters who are turning, or just about turn, into their future selves. Anderson’s nostalgic Valley is a richly rendered weigh station for people waiting out the last heady days of indecision. It is a fondly remembered limbo, where our characters rev their engines in neutral for just a moment more. It also keens with the melancholy knowledge that much will change soon. Whether Gary and Alana continue to live here or not, the Valley we are seeing is a place that they will soon be leaving because that incarnation of the Valley will soon be leaving. Gary is already looking in the rearview at his life as an actor. And the things he thinks will be part of his future won’t be part of the future for very long. It’s a good thing he gets out of the waterbed business early. That said, Atari and Nintendo are just over the horizon, waiting to make life as a pinball entrepreneur a little more complicated too. Anderson keenly sets his film on Hollywood’s outskirts. We catch glimpses of silver screen glitz. We meet talent agents and old actors. Barbara Streisand’s unhinged, Shampoo-inspiring boyfriend Jon Peters (Bradley Cooper, brilliantly putting the movie in a chokehold for a white knuckle 15 minutes). But this is mostly about life just outside of the silver screen’s glow. It’s a world where some see their dreams of fame come true and the rest get about to the business of figuring out something else to do with their lives. It is about the restlessness and uncertainty of young adulthood, manifested as a real, physical space that both nurtures and restricts. A place that sates and frustrates. The place that you either break free of or surrender yourself to. Anderson imagines the strong hold of one’s old home and the siren’s call of a new life both seem impossibly strong. It is almost thematically straightforward by Anderson standards. A luscious ode to one’s hometown and an intoxicating meditation on growing up. What makes it more than just the latest “high school movie” is how much fun it has imagining this place and the inner lives of its denizens. It soars where Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast felt flat because, while we may have seen countless memory plays about artists and the places that raised them, nothing in Licorice Pizza feels cliched or stock. Like Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird, it succeeds by immersing us in deliriously rich details. It hums with a sense of lived experience.

Licorice Pizza is a story of people in strange, intoxicating transitional states. A 15-year old already has decided he has it all figured out already – in spite of the fact that his only heretofore career path is rapidly peeling away from him – and he doesn’t seem to see how ossifying that early might not be an entirely good thing. A reverse mirroring in ways touching and toxic is an impetuous, hot-tempered, occasionally self-sabotaging twenty-something who hasn’t officially decided on anything. Their first time really hanging out together is with him as the established professional and her as his timid, star-struck handler. “I’m his chaperone,” Alana whispers breathlessly to a fellow stage parent, as Gary enjoys his last moments under a spotlight, almost completely impossible to make out behind a chorus line of smaller, cuter talent. These character are not just nuanced, but have a keen kind of interlocking complexity. Gary Valentine carries himself like a 38-year old small business owner, but he is also every bit as immature as his fifteen years. He sabotages a job when a customer is rude to him and Alana has to bail him and his little brothers out of a legitimate ass-whooping. Gary obliviously, chauvinistically gives credit for the narrow escape to both of them. For as sweet and endearing as he can be, he already takes her for granted like some jaded salesman husband. And Alana, in spite of being stalled in her life for most of the film, also has an unmistakable self-possession and shrewdness. She makes her questionable decisions, whether making out with a stranger in a fit of jealousy or agreeing to be part of an aging actor’s dangerous motorcycle stunt, with an unflappable sense of purpose. She has all the maturity Gary still lacks, even if she sometimes balks at using that maturity. “I think it’s weird that I hang out with Gary and his fifteen-year old friends all the time,” she blurts to her sisters between tokes on a joint. Unlike her pimply, posturing counterpart, Alana knows she has a lot left to figure out about her life. As he demonstrated in The Master and There Will Be Blood, Anderson has an impeccable gift for developing characters alongside and in opposition to each other; that bounce off of each other in richly literate fashion. Each character has a way of teaching us facets of the other character in ways far more revealing than any monologue could. Ever since Boogie Nights‘ vast ensemble disco-danced together and sometimes heartbreakingly apart from each other, Anderson has been perhaps the best working choreographer of dazzling character arcs. He is a virtuoso of setting motivations in motion and letting fascinating psyches explode across the screen.

And as Licorice Pizza‘s characters stall internally, one of them spinning his wheels with money-making schemes and the other anxiously biding her time to put key to ignition, Anderson uses all his dynamic skill to make the year’s most liberated motion picture. He gives voice to the growth and movement Alana and Gary crave by creating a chugging, choogling, hurtling rock anthem of a film. Licorice Pizza is a hot rod, a thing of pure beautiful forward momentum. Anderson’s images are candy-coated, his period-appropriate soundtrack fun and swinging and impeccably cool. He directs the year’s most giddily white-knuckle scene using a box truck, an empty gas tank, and the winding Hollywood Hills. He also makes a high school’s class photo day feel invigorating. No 2021 film moves this confidently or energetically. Licorice Pizza moves and moves and moves. Its characters are often seen in full sprint, a physical expression of what they still can’t quite figure out how to do emotionally or professionally. Of course, it is sometimes easier to just move spastically than to do nothing. This is especially true when you are young and feel like you’ve spent your entire life waiting to be allowed to move, to find freedom and self-determination. The ending to The Graduate, sometimes misinterpreted as a joyous cry of youth rebellion, quietly implies that there is a cost to the rash action of adolescence. There is sometimes a price to be paid for the romantic decisions of youth, once we crest and hit the plateau of adulthood. After the rush of moving, there is still the living with whatever moves we have made. I would not say that Anderson ends Licorice Pizza with a Graduate-level note of melancholy (far from it!), but I do wonder if critics of the film’s romance plot aren’t overlooking a note of critique that the ending’s exuberance masks. Gary and Alana merrily running off together as a couple does not mean that the film entirely endorses that choice; that their choice, as exhilarating as Anderson renders it, is uncomplicated or even morally cool. Like The Graduate‘s characters, they will eventually reach a destination, tire of sprinting, ease into a life with less dramatic highs. The adrenaline will die down, and then the real, patient business of living day to day will begin.

Because it is a film about limbo states, about trying to playact adulthood before you have quite gotten there, I find Licorice Pizza‘s most moving scenes to be the ones where flashes of adult life intrude upon the dreamy 1970s idyll. Where Gary and Alana come face to face with actual adults and realize how little they know of that realm of life. In a fantastic scene, Alana nails an audition for a proper film with a handsome but aging action heartthrob (smartly played by Sean Penn as a charismatic, slightly pretentious enigma of movie stardom) After bagging her first role, Alana lets him whisk her away for drinks at Glendale’s fanciest fanciest supper club (Gary jealously eyes her from his usual table). She feels dizzy and proud to be seen out with a real celebrity, a real established professional in one of the lines of work she is trying to break into. But it also soon turns into a confusing experience for her and Alana starts to feel like she may have time-traveled into a future she isn’t ready for or isn’t ready for her. Peen’s waning star is somewhere off in a dreamworld of his own, a smoky old Hollywood reverie. He reminisces softly and wistfully about far-off places and memories that mean nothing to the young lady sitting next to him. Is this man talking about old movies he starred in, old life experiences or both? He is galaxies removed from her, transported on the wings of ecstasies and regrets that Alana knows nothing of. He does not register for a moment that she isn’t following a word of what he’s saying and it is doubtful it would matter if he knew. In a moment, Alana feels just as alone at her table for two as Gary is at his own. And when she finally drifts back to earth at the end of the night, it is Gary who is still her closest friend and it is Gary who she will walk back to her noisy, crowded home with. Licorice Pizza‘s secret poignant weapon is in how it uses glimpses of a grown-up world that its two leads still do not fully grasp. Alana and Gary are characters we come to love, but their kind of performative maturity still has the arrogance of youth about it. Time in the adult trenches, for all it can wear a person down, will also teach them humility and patience. Right now they are both too reckless with one another’s feelings and at the same time too entitled to each other’s attentions and affections. For all that they bicker and repel each other, they are secretly possessive of one another in a way they do not even quite know what to do with. At another adult dinner that teacher her how much she still does not know, Alana sits between a young politician and the secret lover he cannot be with if he wishes to have a career. The lover is not satisfied with sharing a brief, clandestine meal together with a twenty-something girl seated between them to ease suspicion. “I want you to myself,” the heartbroken paramour begs. “Well that’s just not how the world works, is it?,” the councilman tosses back with matter of fact resignation. How the world works is not a thing Licorice Pizza sets out to strictly define. Speaking the language of adulthood is a tricky thing to narrow in on and Anderson’s film is too generous to lecture. It is enough to say that his endearing but still wayward heroine hasn’t mastered it yet, to say nothing of the overgrown teenager she has paired with. As someone once said about pornography, the San Fernando Valley’s favorite export, I guess Gary and Alana will know adulthood when they see it.