The ending to Barry Lyndon, Stanley Kubrick’s dense, masterfully composed British historical epic, punctuates the exploits and avaricious schemes of its petty social climbers with a terse epitaph: “It was in the reign of George III that the aforesaid personages lived and quarrelled; good or bad, handsome or ugly, rich or poor, they are all equal now.” Funnelled through Kubrick’s unwaveringly cynical view of the human animal (Kubrick’s emphasis was always on the second word), it is an acrid, scathing critique of man’s thirst for forward motion and how little human progress actually means. For Kubrick, the man who made two magnum opuses about mankind destroying itself on a grand scale (Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb and 2001: A Space Odyssey), the idea that every one of us gets anonymously filed under the same mortal footnote is perhaps the only sure source of justice and equilibrium. Whatever benefits we reap through our vanity, selfishness and callous disregard for one another, the clock always gets reset once Death has its say. Nothing of what we did or said here will matter much in a millennium. I noted a similar, though considerably more understated, theme of human ephemerality running through The Assassin, Hou Hsia Hsien’s wuxia film set in 7th Century China during the decline of the Tang dynasty. As with Barry Lyndon, The Assassin relates a tale of political maneuvering in a very specific bygone period, but knows that its characters and their concerns are an insignificant pebble in the meandering river of history. The film listens to the political hubbub of a Chinese province, but its eyes are focused on the timeless land that contains them; the land that frequently dwarfs them, obscures them, and at times erases them from the frame altogether. Because the film chooses to look many centuries into the past, Hou is not simply telling the story of people who will one day die, as all mortals do. Each character he introduces exited from the Earth’s stage centuries before any of us were here. Like Kubrick, Hou is gazing with curiosity at the light of a star that died a long, long time ago. The moments when characters disappear behind the crest of the hill are like momentary reflections of the present. There is an important difference, however, between Barry Lyndon and The Assassin. While the epilogue to Kubrick’s masterpiece seems to view the inevitable irrelevance of the human life as a kind of cosmic justice for humanity’s avarice and disregard for each other, The Assassin implies the same conclusion from a decidedly more gentle angle. The Taiwanese auteur’s lusciously shot, richly textured, and meditative martial arts film knows that human beings and the great societies they erect are just swiftly passing shadows across the Earth’s surface. However, there is none of Kubrick’s righteous relish or sardonic satisfaction to be derived from this fact. It is simply something to be observed, something true.

The plot of The Assassin concerns a time of great, seismic change in China’s history. A title card informs us that the Tang Dynasty is waning and, as a result, many of China’s territories are pulling away from the Empire and operating autonomously. The Empire has made strides to reacquire some of these territories, but a handful continue to assert their independence and plan for the possibility of an imperial invasion. The political landscape of the country is undulating and shifting just as surely as the wide land around it is staying the same. One of the territories still fighting to remain independent is Weibo, which is ruled over by a young general named Tian Jian. Our main protagonist is Tian Jian’s cousin, a young woman named Yinninang. Yinniang’s mother and uncle sent her away from Weibo as a very young child, fearing for her safety amidst the political unrest. Yinninang spent her formative years living with a Taoist nun, Jiaxin, who trained her to become a lethally effective assassin, specializing in eliminating unscrupulous politicians. As the film opens, Jiaxin has ordered Yinniang to kill a man on horseback. She insists that the man, a local political leader, killed his father and poisoned his own brother. Yinniang cuts the man’s throat swiftly and without hesitation. However, Yinniang’s unblinking moral certainty wavers with her next assignment, when she refuses to kill a corrupt provincial governor in front of his child. Jiaxin scolds her for her lack of resolve, and gives her a new assignment. She is to go back to Weibo to assassinate her cousin. Yinniang returns to a Weibo that is still in turmoil over its future. Tian Jian is weighing the decision of whether to work with other disputing territories, and fretting over the possibility of an attack by the Empire. He seeks council from his advisers, tries to assuage the fears of his wife, Lady Tian, and steals off to find emotional support in his mistress, a concubine named Huji who is pregnant with his child. The plot of The Assassin is a dense tapestry of characters with rich histories, but it is also simple at its core, because it is really about Yinninang. Yinniang must return to her childhood home and decide whether she is willing to kill her cousin for what her master feels is a just purpose. The Assassin sometimes feels overwhelming in its insularity, but this is a fitting mirror for Yinniang’s emotional arc, as she flits along the periphery of her old life and home and tries to come to terms with people and places that are no longer familiar to her. The film’s first scene shows us how quickly Yinniang can kill when she wishes to. The rest of the film plays against our knowledge of her deadly skill, as Yinniang searches her conflicted soul and contemplates the morality of her mission. While there is a complex political story unfolding at the center of The Assassin, the film’s true focus is always on the margins, where Yinniang waits and watches. Even when Yinniang is not in the frame, we know we are watching her watching. With many scenes it is less important to know what is done and said than to know that Yinniang sees it and hears it.

What makes The Assassin a true work of art is that its power comes more from seeing and hearing it than from deconstructing it for thematic grist. The Assassin does have some beautiful, subtle themes, and it was a pleasure to marinate in them over the course of two viewings. However, for the sake of full disclosure, I am also a certifiable glutton for thematic analysis. I readily admit to my addiction, and I also concede that this kind of rigorously literate approach does a disservice to a certain kind of film. To be frank, a thorough thematic unpacking is not the approach a film like The Assassin deserves. Even though the film delves into heady ideas about loyalty, rebellion, mortality, and the power of familial bonds, its chief virtues are neither verbal nor ideological. Instead, The Assassin is an almost indescribable visual marvel. And seeing as how the phrase “visual marvel” has been used to praise films like Avatar, Interstellar, and How To Train Your Dragon 2, I have to say that words once again fail to do justice to what Hou has accomplished. A film critic traffics in verbiage, but when a film operates with shots this thoughtfully composed, images of both natural and cultural beauty this ravishing, and a sense of pacing this singularly serene, it becomes difficult for any number of words to capture its power. To loosely paraphrase Jodie Foster in Contact, they should have sent a painter. With enough time and a decent dictionary, I can give my impressions on what drives the fisherman in The Old Man and the Sea or how Pulp Fiction wrestles with moral agency. But set me in front of a truly stunning work of abstract art, and I am impotent. It is a much more difficult matter to explain the power of a splash of color, or a jagged line. Or the way a strand of light shoots through an ancient Chinese bathhouse window. I do a semi-regular podcast with my longtime friend and partner-in-criticism, Robb Whiting. We do a theme-based segment, titled “What’s It All About?”, where we apply the titular question to whatever film we have just watched. I think it’s always a vital first question to ask. It’s a trusty leaping-off point and it personally helps me to get at the fundamental character and thrust of a work of art. But when I ask The Assassin that question, it somehow feels reductive and a bit silly. For the purposes of this film, I cannot succinctly express why the forest green paint on an old clay teapot, or a gleaming, golden toy in the hands of a child, or a red piece of silk wafting on the edge of the frame is beautiful. I cannot tell you “what they’re all about”. They are about themselves. They are immediate, as is the film that contains them.

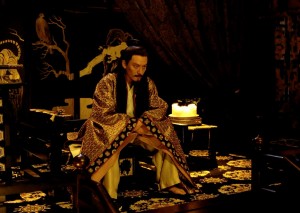

As I watched The Assassin a second time, I began my viewing in a feverish state of note-taking. Occasionally, I would even pause the film to scribble whole paragraphs out of my busy, verbose skull. By the midway point of the film, I stopped doing this. I realized the film had let me in on its themes early on, and there was no need to continue writing them down in different words. The film still had plenty of narrative developments and betrayals and plot twists left to reveal and all of them were thematically of a piece with what had come before. But I also felt the director gently nudging these concerns out of focus, the same way the film regularly blurs its brief bursts of violence and chooses to foreground some tree or hilltop instead. The Assassin is dense with events: political machinations, familial histories, and interweaving relationships among the courtiers and guards and wives and mistresses of Weibo. Still, I came away feeling as if all of that was a passing concern in the eyes of its director. Important for its characters. Insignificant in the grand scheme. All of the intrigue of the plot matters less than our immersion in the myriad stunning environments of the time and place. On top of those monolithic peaks of jade and granite, and down in the dank caves that lie somewhere underneath them. Among the vibrant reds and golds of the court rooms, inside the airy bed chambers full of candle light, and up against the wooden pillars of the temple’s open air hallways. And when the camera pulls back, the temple looks like some giant, glowing hearth, with the cool midnight blue of the natural world all around it. All of this, says Hou, is China. Some of it as it used to be. Some of it as it still is. As the film progressed, my occasional notes began to sound like titles of paintings. Damp Cavern With Torches. Golden Field, Distant Farm House. Misty Lake With Spectral Trees. There must be close to a hundred such “paintings” in The Assassin’s 140 minutes. And all of that is before one walks from the art wing into the film’s dazzling gallery of historical artifacts. The film oscillates between impossibly gorgeous landscapes and interiors that are packed to bursting with jewels, teacups, baubles, paintings, tapestries, musical instruments, and fabrics.

The Assassin is an ineffable poem of transcendent imagery. Then again, while its images are so striking as to render words irrelevant, I still think there is perhaps some greater idea to all that beauty. It all gets back to Kubrick and the idea that human endeavors, words included, do not amount to much in the end. I believe that is true. When compared to the lush greens of the hills outside of the palace, or the pink pastels of a blossoming tree, or a great white billow of fog scaling its way up a cliff, even the greatest works of painters and musicians and artisans are doomed to fall away in short order. The hills, trees, and cliffs have been here since time immemorial, and will likely still be here when our testaments to human expression have been lost or fallen into disrepair. But what makes Hou’s film generous where Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon is acidic is that Hou finds beauty in the impermanence of human beings and their endeavors. As soon as Yinniang is sent to Weibo on her killer’s errand, the film changes from black and white to color, and the next sight we see is a lovely shot of tall trees reflecting in a lake. It is dusk. The trees are seen in silhouette. On closer inspection, one of them does not look like a tree at all. It is a nearby temple just behind them. It is bathed in the same shadows, framed as if it were a part of the thicket. In moments like these, The Assassin transcends being a simple object of beauty and becomes a tribute to beauty in all its forms. Some works of art are mountains and forests and rolling hills and they are a part of the ageless Earth. Other works of art are temples, sculptures, and paintings, and they are the works of human beings, who are born and soon pass away. In a relatively short amount of time, their art passes too. That temple is probably long gone. But, for as long it lasted, it was fit to stand with the most beautiful of nature’s works. I suppose we are afforded the same honor.