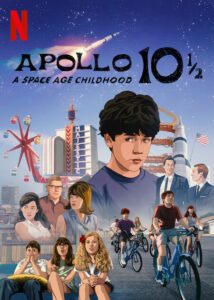

I’m a little leery about calling certain films minor to a director’s filmography. For one thing, it tends to feel too relative. A minor film from Kubrick, Coen, Altman, Rohmer, the Andersons (P.T. or Wes) and others dwarfs the best films of your average director. A so-called minor Scorsese film (let’s say Hugo) still tops almost the best films Robert Redford, Stephen Daldty or Tom Hooper have ever made and nobody goes around calling Quiz Show (an extremely fine film) minor. So I don’t want to start my review calling Richard Linklater’s wonderful, effervescent Apollo 10 1/2: A Childhood Odyssey minor just because it happens to only be the eighth or ninth best film of the laconic dreamer’s sterling career. It is far too strong and personal a work to be slighted like that. But I do find it interesting, with directors who have a substantial body of freat work, to look at the films that fall somewhere below their masterpiece colleciton. I find that the films just outside of that realm often have a way of enriching the films just above them and sometimes give us a lot of fascinating insights into the directors themselves. Think of the 2022 films from James Cameron and Steven Spielberg, which may fall just outside of their most perfect opuses but also act like beautiful prisms playfully reflecting some of the ideas and themes those auteurs have spent their careers exploring. The ways films like these, and like Apollo 10 1/2, play within their directors’ filmographies is fun, rewarding and infinitely more interesting than the question of whether those films will be admitted to the elite canon of their very best work. Besides, while he has made no less than five perfect films by my count (the Before trilogy, Dazed and Confused and Boyhood, with Waking Life not far behind), I can’t imagine Richard Linklater, the good-natured stoner bro of filmdom, loses a lot of sleep over words like “perfection”. His ace in the hole has always been his meandering, ramshackle nature; the way he arrives at beautiful and deep revelations with all the unhurried nonchalance of a day drinker finding a cool tidepool at a beach party. He is a practiced expert at a very rich and warm sort of aimlessness and he has found perfect material in the halcyon glow of his own childhood in 1960’s Houston. Not unlike fellow longhorn Terrence Malick, he finds deceptively heady ideas about life in the humidly carefree atmosphere of a Space Age Texas suburb. I see Apollo 10 1/2 as The Tree of Life‘s charmingly low stakes little brother, albeit set in a place where trees of any kind are scarce to be found.

Richard Linklater rarely misses a chance to wax poetic on the nature of time, memory and consciousness. In his rotoscoped philosophy gem Waking Life, he appears as himself to muse about the nebulous border between dreams and death, the present moment and all the moments that have passed. A few years later, he had Ethan Hawkes’ character in Before Sunset put it succinctly: time is a lie. Maybe every moment is a dream of past, present and future all laid like transparencies on top of one another. Apollo 10 1/2 has that dreamlike quality that makes time feel slippery and illusory. Specifically, it feels like a youthful daydream. It presents itself initially as a bit of historical fantasy in which a young Linklater is asked (for the most adorably cockamamie of reasons) to secretly pilot the Apollo 11 module to the moon weeks before the real mission will be televised. But that imaginative boys adventure merely ends up being the film’s bookends. The meat of Linklater’s animated slice of autobiographical life is about the present adult Richard Linklater (given voice by three-time Linklater muse Jack Black) reminiscing about his carefree days in 1960’s Houston at the dawn of the Space Age. We learn of his father’s work for NASA (purely administrative to his children’s eternal disappointment) and what it felt like to live on the periphery of humanity’s most daring technological achievement. But what we really get the most of aren’t observations about space travel but seemingly trivial details of that time and place. The music and movies and campy classic television shows (Dark Shadows is just as gripping to the Linklater children as updates from NASA and both jockey for screen time on the old TV set) of the day. The neighborhood faces and the rambunctious, occasionally hazardous ways adolescent Houstonians passed the time. Shot through with Linklater’s inimitable sense of childlike enthusiasm, Apollo 10 1/2 might be cinema’s greatest feature-length tangent. The transcendent art of the decade and the sprawling banality of the expanding Houston suburbs all swirl together into a bewitching, winningly observant act of remembering, which (in true Linklater fashion) becomes a meditation on what defines the times and what we choose to recall. The Linklater patriarch may grumble when his four children flip over from discussion of the Moon landing to a cheesy science fiction program, but both pieces of media were formative for the director telling this story. In the end, we reconstruct a story of the past with all the details we have and it’s no great matter if one memory is a watershed event and another one is just Herman Munster’s face. There are no minor works in the category of one’s memories. Reminiscing is not only a personal act, but a creative one as well. Memory is not bound by strict parameters of social importance. As Apollo 10 1/2‘s fictitious bookends demonstrate, it is not really even bound by strict parameters of fact and fiction.

Apollo 10 1/2: A Childhood Odyssey is doing a lot of heady philosophizing in that sweetly shambling Linklater way, but those shy about intimidatingly cerebral films will find as much to love here as those hoping to get a heady intellectual contact high. With this director, an amiable, buzzed vibe is just as important to his sensibilities as literary references and tingly thought experiments. The head and the heart are always in touch with each other in a Linklater film. He makes movies for art-loving romantics everywhere. It has also long been my feeling that he is maybe just a bit underappreciated as a visual and tonal stylist. Like his French New Wave influence Eric Rohmer, Linklater is drawn to the pleasure in words and talk, which sometimes gets him labeled as talky and downplays what a distinct and flavorful cinematic language he has honed. Long before he made Waking Life (one of his three singular animated marvels alongside Apollo and A Scanner Darkly), he hit big with the one-two punch of Slacker and Dazed and Confused, films that seemed to have one foot in bucolic Texas and one foot in some dream realm. In Apollo 10 1/2, he captures the languid sprawl of an endless Houston summer partly because he is trying to evoke the reality of his suburban origins. But the aimless, humid rhythms and heat waves of Texas also feel a lot like the haze of memory itself and the way that aesthetic fits both the terrestrial and the subconscious is about as purely Linklater as it gets. The underrated quality of Richard Linklater the visual storyteller is how he subtly captures something that feels like nostalgia’s essence; a sweet, smoky buzz like the first beer with friends on a porch as the heat starts to dissipate. What makes Apollo 10 1/2 feel so substantial, in spite of its breezy tone, is that it is positively pickled in that woozy sensibility. it has the kind of scruffy warmth that is not only characteristic of 1960’s home videos but also somehow seems to bottle up every other adorably shambolic thing Linklater ever experienced, from the soft scratch of Herb Alpert LPs to those cartoon shorts MTV aired between commercial breaks. The primordial stew that birthed his gentle but endearingly rambunctious aesthetic smells like cheap weed, french fries and gasoline. Linklater announces this is to be a film about the Moon landing and then lets every other pop culture touchstone wash over the lens. As the semicolon in the title implies, it’s as much about childhood’s inner space as it is about things floating outside the Earth’s atmosphere.

With Linklater, small details are given equal and sometimes greater importance than the weightier matters. His beautiful, impossibly romantic Before Sunrise (and its arguably even richer sequels, Before Sunset and Before Midnight) depict an organically unfolding conversation between two people who are falling in love with each other. The film finds room for philosophical musings on love, faith and death, but also plenty of time for art, beer, food and pinball. In Linklater’s oeuvre, the small grace notes of what we enjoy and do for fun are essential parts of what makes life rich and interesting. They are not less important than the big cosmic questions, nor are they more so. In Linklater’s gorgeous and goofy imagination, the cosmos and your favorite movie are all connected in one life-affirming link. This idea was given its most cohesively powerful expression in Boyhood, where major life events like graduations and birthdays were deliberately left out to make room for baseball games and digressive conversations; things that a lesser filmmaker might have left off for being inessential. The Linklater school of thought tells us that the mundane and the trivial and the purely fun experiences we have are actually the most essential in defining our lives. Most people go to school or get a first job or have major rites of passage, but those smaller specificities are what help make our lives singular. They are what make our lives our own. Apollo 10 1/2 is, above all, a superb little coda to Boyhood; a winsome exploration of how the little things stick with us and shape our stories. Linklater teasingly starts Apollo 10 1/2 with his surrogate self asked to embark on a nationally vital space mission, a Marvel-level astronaut adventure. And then he tables all of that before it can even get started so that a charmingly enthusiastic Jack Black can gush about all the cool games, music, shows and places that made up life down on 1960’s Earth. Linklater will send us off to the stars in good time (but not a long time, as one Linklater character once said) but only after he tells us about how much he loved The Twilight Zone and his favorite jazz record and the treasured Texas tradition of pouring a ladle full of hot chili into a fun-sized bag of Frito Lays. This is why Apollo 10 1/2 couldn’t possibly be minor Linklater. Minor films don’t typically have the DNA of a director’s entire personality inside them. Richard Linklater knows about films what great travel writers know about cities. You’re never going to experience as much joyous, spontaneous life if you only stick to the gift shop maps and the big tourist sites. He lovingly takes the audience around his Houston just as Slacker took us around his Austin. And that means he’d much rather take us to Houston’s adorably scruffy Disneyland simulacrum, Astro World than to the major museums and historical sites. The most enchanting sights to see are little oddities and they can only be found off the main drag and down the back alleys of Richard Linklater’s memory.

Anyone who knows me well knows that Richard Linklater is one of my favorite living filmmakers. More than a favorite, he happens to be a director who taps into some essential part of my core. I think he is objectively a genius in terms of how he writes and how he crafts his scenes but he’s also my ur-example of a director who is just completely for me. I’m an empathy-loving, pop culture-fixated intellectual humanist romantic through and through. I love a whole host of directors with a diverse array of perspectives (I think Michael Haneke’s great and am also proud to say that I don’t think like him) but if I’m being honest, I probably am Richard Linklater. He stands with the great empathetic directors like Ang Lee, the late Jonathan Demme, Greta Gerwig and, most notable, the visionary Eric Rohmer. Whatever subject he lights on, he renders it with a palpable love for people. I leave each of his films with my intellectual curiosity recharged and my appreciation of humanity restored. He’s a surprisingly ideal fit to tell the story of one of Earth’s most purely optimistic moments. He comes at it from his own charmingly low key angle. His focus on tiny details of 1960s life cohesively ties into the idea that the Moon landing itself was the result of thousands of lesser known people. Apollo 10 1/2 is Linklater’s invitation to see the Apollo 11 mission just a little differently; to zoom in and take in the little granules of cultural context surrounding it. Just as he shows us his personal experience of the culture through all the pop culture ephemera he absorbed as a kid, he makes one of the most public, well-documented moments in human civilization feel intimate. He asks us to consider people like his father, working with spreadsheets and purchase orders far from the launch pad and the flash bulbs. In a moving moment following the landing, Linklater’s father marvels that the astronauts and flight control pulled it off. His wife tenderly reminds him to include himself in the victory, saying, “We all did.” In a film whose default tone is sweetly breezy, Richard Linklater remembers to show us how moving the Apollo 11 mission was for all the many souls who contributed to it. And he follows it up with another moment that touched me to no end. When the night’s groundbreaking broadcast is done and the stations sign off (as they did back in the early days of television), the Linklaters end their unforgettable night in the same way they end every night. They turn off the set, exchange “good nights” and “I love yous” and slip of to bed. Historical milestones are a great change of pace, but there’s just something about the reliable rituals that are waiting for us each and every day.

When I heard Richard Linklater was going to make his first new animated film since the 2000s, I said to myself, “It’s about time!” It was both an exclamation of excitement and a safe prediction about the contents of the film itself. It’s almost always about time with this filmmaker. How it passes, how it lingers, how we mark it. How maybe it’s a lie but also how very real the waking dream of time feels. Apollo 10 1/2 is also a sly film about nostalgia. a word that I don’t always associate with positive connotations. A long soak in a bath of nostalgia can be bewitching and intoxicating, but it also has a pesky way of making our brains waterlogged. It can cloud the senses and distort our memory of the times we are nostalgic for. It can cause people to get too bogged down in the moments of their own coming of age to the point they become oblivious to the beauty of the present moment. I have rolled my eyes repeatedly at members of older generations who claim that they just don’t make art and pop culture the way they used to. I assure them that, if they paid more attention, they would see that they very much do. More recently, I’ve grown to watch members of my own 90s-kid generation fall prey to the same habit. And I have to remind them that the present has art to rival the time of their childhoods. As has every year between their childhoods and now. Apollo 10 1/2 quietly critiques nostalgia by noting how little the Moon landing did to alleviate the many systemic evils of that time. But at the same time, it pulls us into an irresistible nostalgic reverie so powerful that we spend a hundred minutes helplessly pulled along in its current. Linklater isn’t really a lecturer. He’s not actually out to give us a polemic on the scary grip of looking backwards. His way is just to show us the hypnotic eddy of nostalgia and to ask with his characteristic stoner bemusement, “Ain’t that something else?” It’s for us to decide how much the nostalgic free associations of Apollo 10 1/2 are fun and sugar rush pleasurable and how much this exact kind of breathless idealizing of the past presents uneasy implications about memory’s power to gloss over harder truths. Linklater? He’s just out looking for pockets of wonder and weirdness and beauty in the most unassuming places. He’s just wandering the beach at dusk in search of tidepools. And this latest little pool looks like it has a whole universe inside of it.