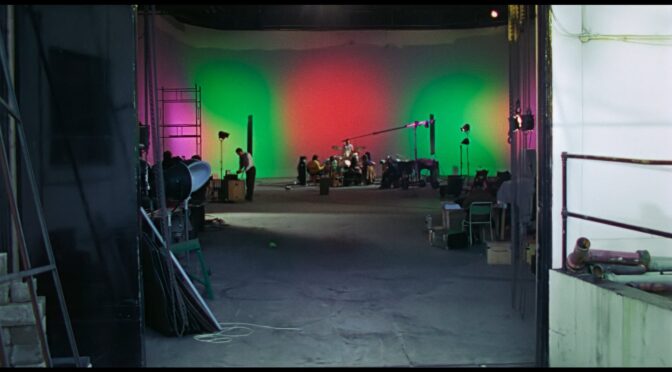

Peter Jackson’s three-part, fly on the wall documentary project The Beatles: Get Back (released as a miniseries on Disney+) is a great many things over its more than eight hours. But what it is maybe first and foremost is a loving reclamation project. Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s 1970 documentary Let It Be was released to mostly mixed reviews and dismissed as a disjointed muddle brought only occasionally to life by the presence of the band’s music. Its perceived aimlessness (even at a brief 88 minutes) with rehearsal scenes intermittently punctuated with arguments, might have just been confusing and unfulfilling except for one major offscreen development. The Beatles had broken up barely a month before Let It Be‘s release date. And so, understandably, a disjointed hash of a film was seen contextually as the last dismal bit of found footage from the scene of a devastating falling out. A gloomy, incomplete recording of a bruising cultural loss. A scrambled black box that had happened to capture the death of the entire 1960s. Gimme Shelter‘s less coherent, generally mediocre cousin. The complex, 22-day album recording process (during which they wrote most of the songs for their closing masterpieces, Abbey Road and Let It Be) had been condensed into a woefully truncated hour-and-twenty, and I think a lot of people filled all that empty space with their own grim speculation. Chief among them is the old chestnut that John Lennon’s soon-to-be wife Yoko Ono’s presence in the recording studio was a major catalyst in The Beatles disbanding. If nothing else, Hogg’s Let It Be documentary helped turn Ono’s name into a shorthand for meddlesome significant others that muck up a band’s creative process. Never mind the fact that Paul’s own girlfriend was also often present or the fact that Ono is mostly seen quietly watching and drinking tea. Hogg’s film notably omitted the few days when George Harrison prematurely quit the band for reasons having seemingly nothing to do with anybody’s girlfriend and much more to do with feeling creatively neglected by the Lennon-McCartney songwriting juggernaut. Whatever Hogg’s good intentions, 1970’s Let It Be feels a bit like tabloid journalism and it fed shallow, reductive takes about the band’s last days and who was to blame. Peter Jackson’s miraculous and generous document (made from Hogg’s wealth of footage and stunningly restored by Jackson and his team) takes what was a superficial blurb and opens it up into a nuanced, winningly digressive essay. In place of an autopsy of The Beatles, he finds a vibrant, poignant and bittersweet tale of beautiful art and painful personal change. The Beatles: Get Back is a corrective tonic to a saga that was once tinted by acrimony. You will finish the film mystified as to how anyone spent all these years laying the blame on sweet, humble Yoko Ono. As if life and art and interpersonal relationships are ever so simple. You will finish the film with a lot of newfound clarity and empathy for everyone involved in that final month that would be the world’s greatest band’s last hurrah.