Peter Jackson’s three-part, fly on the wall documentary project The Beatles: Get Back (released as a miniseries on Disney+) is a great many things over its more than eight hours. But what it is maybe first and foremost is a loving reclamation project. Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s 1970 documentary Let It Be was released to mostly mixed reviews and dismissed as a disjointed muddle brought only occasionally to life by the presence of the band’s music. Its perceived aimlessness (even at a brief 88 minutes) with rehearsal scenes intermittently punctuated with arguments, might have just been confusing and unfulfilling except for one major offscreen development. The Beatles had broken up barely a month before Let It Be‘s release date. And so, understandably, a disjointed hash of a film was seen contextually as the last dismal bit of found footage from the scene of a devastating falling out. A gloomy, incomplete recording of a bruising cultural loss. A scrambled black box that had happened to capture the death of the entire 1960s. Gimme Shelter‘s less coherent, generally mediocre cousin. The complex, 22-day album recording process (during which they wrote most of the songs for their closing masterpieces, Abbey Road and Let It Be) had been condensed into a woefully truncated hour-and-twenty, and I think a lot of people filled all that empty space with their own grim speculation. Chief among them is the old chestnut that John Lennon’s soon-to-be wife Yoko Ono’s presence in the recording studio was a major catalyst in The Beatles disbanding. If nothing else, Hogg’s Let It Be documentary helped turn Ono’s name into a shorthand for meddlesome significant others that muck up a band’s creative process. Never mind the fact that Paul’s own girlfriend was also often present or the fact that Ono is mostly seen quietly watching and drinking tea. Hogg’s film notably omitted the few days when George Harrison prematurely quit the band for reasons having seemingly nothing to do with anybody’s girlfriend and much more to do with feeling creatively neglected by the Lennon-McCartney songwriting juggernaut. Whatever Hogg’s good intentions, 1970’s Let It Be feels a bit like tabloid journalism and it fed shallow, reductive takes about the band’s last days and who was to blame. Peter Jackson’s miraculous and generous document (made from Hogg’s wealth of footage and stunningly restored by Jackson and his team) takes what was a superficial blurb and opens it up into a nuanced, winningly digressive essay. In place of an autopsy of The Beatles, he finds a vibrant, poignant and bittersweet tale of beautiful art and painful personal change. The Beatles: Get Back is a corrective tonic to a saga that was once tinted by acrimony. You will finish the film mystified as to how anyone spent all these years laying the blame on sweet, humble Yoko Ono. As if life and art and interpersonal relationships are ever so simple. You will finish the film with a lot of newfound clarity and empathy for everyone involved in that final month that would be the world’s greatest band’s last hurrah.

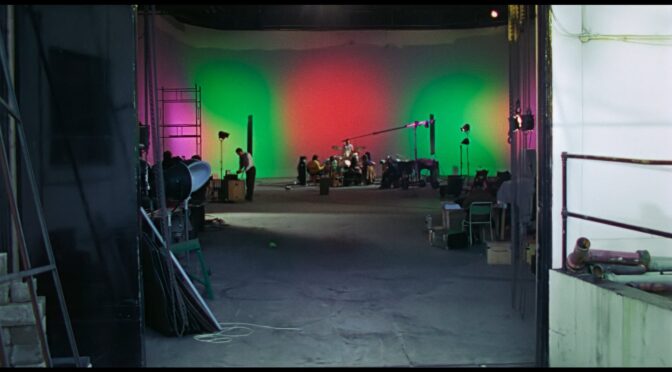

After a breathless and moving (and musical, of course) montage of the life of The Beatles, from the first time John and Paul, the film drops us in the late Sixties. The film documents a span of twenty-two days in January of 1969. Shortly before this moment, the band had performed live together for what was the first time in two years. Realizing how much they had missed it, As the film begins, The Beatles have booked a space at England’s Twickenham film studios (where drummer Ringo Starr would soon film a comedy with chameleonic character actor Peter Sellers) and set about to write new music. Their challenge is to not only come up with a whopping fourteen new songs for a new album, but to record them all as part of a live TV special. A band that has seen its individual members scatter off in pursuit of personal passion projects has given itself seventeen days to create, memorize and play a full album’s worth of new material without the use of any studio tricks. It is not spoiling too much to say that complications ensue, that the visual nature of the special is argued over (Michael Lindsay-Hogg has his heart dead set on the band performing at an outdoor amphitheater on the North African coast), deadlines are pushed back. Having reviewed all of Hogg’s footage, Peter Jackson felt moved to tell a fuller story about these three weeks. He wanted to make this epic to show that there was so much more here than just discord, than the seeds of the band’s breakup. But that said, a tone of dysfunction does rear its head intermittently. The passing of the band’s mentor and manager Brian Epstein less than two years prior hangs heavy over the group and Paul McCartney feels a sudden need to impose some now-absent sense of structure and discipline onto the band. He speaks gently and patiently to his friends, but whiff of paternalism is unavoidable. George Harrison, who has always felt like a third fiddle (the producers always pushed Lennon and McCartney as the key songwriters) feels more dismissed than every by this version of Paul. And many of George’s ideas, which feature a more dense, jazzily ornate sense of musicianship, are dismissed because Paul favors simplicity and tonal clarity. John Lennon seems a million miles away for the first handful of days, probably wishing to spend more time with his spouse or on his Vietnam activism. And Ringo patiently watches and tries to lend an ear to whoever needs it. Because they all need to hear each other and hearing each other, like music itself, takes practice. The Beatles: Get Back starts with a band struggling to find itself again, takes us through three weeks that produced some of the most famous and brilliant songs ever written, and culminates with the famous, much-parodied final concert on the rooftop of London’s Apple Studios. In between is humor, heartache, and pure magic. I have great admiration for the arc of Peter Jackson’s career (The Lovely Bones and The Hobbit trilogy sadly excepted), from gleefully tacky goremeister to Oscar-winning traverser of Middle Earth. He only recently moved into documentary, vividly colorizing the British World War I experience for 2018’s very strong They Shall Not Grow Old. It feels strange to call The Beatles: Get Back his best film, not only because of how tremendous the first two Lord of the Rings films are but also because the documentary genre still feels so uncharacteristic of him. That Peter Jackson is still only two films old after all. And yet, the glorious, detailed and humane sweep of this 8-hour opus (not to mention the outstanding feat of restoration and editing it represents) is enough for me to at least float the idea. I’ll save the actual debate for another day and just say that, in no uncertain terms, The Beatles: Get Back is exceptional and transcendent. And that, after more than a decade in the wilderness post-Rings, Jackson has not only returned to us but grown in a way I never expected of him. Call him Peter the White now.

The Beatles: Get Back sets out to dispel easy, pat theories on what broke The Beatles up. It is a notion the band would have surely approved of. The four lads repeatedly skewer tabloid rumors of their demise, full of fisticuffs and divorces, by reading them out loud and mocking them. At one point, the band has a rock-and-roll freakout session, jamming thunderously while Paul reads a particularly glib gossip article over his bandmates’ din. At the same time, the question of where they finally lost the desire to play together is a compelling one. Some old theories are debunked. While John and Yoko had been spending a lot of time together, Paul very sympathetically defuses that as being a major issue. “Let the young lovers stay together,” he says. The much larger issue that appears (and again, was given much less focus in 1970’s messy post-mortem) is the alienation of George Harrison and his songwriting talent. Jackson lets us come to our own conclusions but he gives us a rich array of perspectives and details. He lets the discussions play out in full. Yes, Paul and George were disagreeing more about the sonic direction of The Beatles, but these same sessions also forged two albums that many place in their top five (this critic considers Abbey Road to be their best and maybe the best album of all time). The film lets us see how four talents this powerful and restlessly were evolving in new and different directions. And nobody was wrong here. While I happen to favor Paul’s clean, emotionally direct popcraft to Harrison’s more Clapton-esque, ornately filigreed style (and it’s not as if I don’t love Harrison masterworks like “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” and “Something”), that opinion only goes so far as what I like from The Beatles. I also happen to think that George Harrison made a compelling argument for his oft-disregarded ideas by turning around and making the best solo record any of them ever made, the towering triple-disc masterpiece, All Things Must Pass. The beauty of The Beatles: Get Back is in how understanding and non-judgmental it is, so that it really just becomes a lovely and mature meditation on how bands (and friendships) change and grow. And sometimes grow apart. It manages to become overwhelmingly life-affirming and joyful without minimizing how painful change can be. And while we know watching this footage that The Beatles are barely a year away from hanging it all up, Get Back isn’t actually about watching a growing rift. It’s actually about watching four friends heal and play together again. It sadly happens that this will be the last time. But Jackson blesses us with a chance to see them come together and to witness the astonishingly beautiful results.

After all the rumors and arguments and creative differences have faded away, what remains is the band’s ingenious, whimsically soulful music. To call The Beatles the greatest band in history has always felt too dismissive of the sheer wealth and diversity of music out there (both the Chuck Berry rock pioneers who inspired them and the multitude of musical geniuses who sprung from their influence). And yet, the mantle feels fitting when you watch them work up close. More than anything, Get Back is maybe the most astoundingly detailed document of collaboration and the creative process that I have ever seen. I would have to go back to 2007’s musical masterpiece Once to find an ode to both the doldrums and the ecstasies of music-making that operates on this level. Peter Jackson’s gorgeously intimate window into the making of two timeless albums is great not just because the music is great but because it is so perfectly keyed in to the connection that develops between long-time artistic collaborators. At one point Paul gushes about getting the new songs honed enough that they become second nature. He says he’s excited about moving on to what he calls “the riff stage”, and when he says those words, John’s face lights up and they both share a knowing giggle. The film has a way of bringing you in to the codes and shorthand and inside jokes of the band. We get to see the shared language they have developed . It is rich and compelling to watch them navigate an arduous process charged with the joys and stresses of more than a decade working together. In the first of its three parts (arguably my favorite segment, though each one is perfect and revealing in very specific ways), Get Back has the patience to begin with the band mired in claustrophobia and writer’s block. Watching the opening minutes, one can see where Hogg’s more negative document may have come from. Needing still a dozen songs, Paul sits down and starts to improvise, finger pick, jam. As if to wave away the mental haze hanging over them in a flurry of strums. And then, all of a sudden, like a lighthouse’s beam breaking through a fog, the strains of “Get Back” emerge. And the fact I love this band obviously helps elevate that moment, but I think something in that scene transcends The Beatles themselves. The simple act of starting from a desperate, despondent place and then seeing a brilliant, now-famous song suddenly materialize out of the ether is so impossibly exciting. And, after the gloomy dysfunction of those opening minutes, it is also tremendously moving. It’s not as if I didn’t expect to hear Beatles songs in a Beatles documentary. But Peter Jackson builds up the fatigue, miscommunication and general stakes so well that hearing something finally come together feels like a triumphant act of willpower. You sense the daunting achievement that is the writing of one, just one, perfect song. And then more start to arrive. “Dig A Pony”. “Two of Us”. “Carry That Weight”. Oh yeah, “Let It Be”. If 2021 held more transcendent scenes than Paul unveiling “She Came In Through the Bathroom Window” to a visibly, almost begrudgingly impressed John Lennon (it is the moment Lennon’s apathetic malaise truly dissipates, I think the moment we get him back), they are few and far between.

What is also moving is just that Jackson has removed and corrected any lingering traces of bitterness from the story of this band. I think of Celine’s words to Jesse in Before Sunset when they finally reunite after nine years apart. “Now that we’ve met again, we can change our memory,” she says. “It no longer has that sad ending of us never seeing each other again.” Jackson’s miracle is to change our memories. The Beatles disbanding didn’t mean they never spoke again, but the impending breakup came with such a seismic tone of era-ending finality that it has always cast a shadow over their last burst of creative output. With The Beatles: Get Back, Jackson sheds warm sunlight on this complicated but beautifully productive final chapter. The creation of Let It Be and Abbey Road wasn’t the only beautiful thing to come out of all this. The footage itself and what it says about this band and friendship and music in general is an absolute good. Peter Jackson’s momentous, painstaking accomplishment is really a humble act of asking all music lovers to revisit and reevaluate. It is the same thing any good critic asks of a reader. Whatever you believe about a story, remember to always reconsider. The Beatles: Get Back is like the band’s wonderful self-titled album (famously known as The White Album). It is a sprawling, digressive anthology that bursts with moments of humor, pathos, whimsy and love. And so, these last two albums were not the products of mere strife and dysfunction, but of something more richly optimistic. Yes, the band would shortly break up and they would sadly never fulfill Paul’s wishful prophecy of playing together as old men. But here, lovingly touched up and joyfully observed, is a beautiful, hopeful work of art about the making of two beautiful, hopeful works of art. It’s another good something to come out of that time and an exuberant recontextualization of music history. For a band that gave the world so many good and tender things, Get Back feels like a final give given back to the band and to anyone who ever loved them.

And one last word on the subject of recontextualization. In the same way Yoko Ono has been unfairly yoked to The Beatles’ break up for decades, Ringo Starr has always gotten a bit of a raw deal too, just in terms of his critical appraisal. Lennon and McCartney wrote the bulk of rock and roll’s richest songwriting catalogue. George Harrison wrote phenomenal songs like “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” “Something” and “Here Comes the Sun”, and was a slept-on genius who should have been allowed to contribute more. And Ringo Starr banged away on the drums. He had a big nose and big sad Eeyore eyes and he played hangdog comic relief (marvelously well) in the film A Hard Day’s Night. And he wrote “Octopus’s Garden”, the perennially mocked middle child of Abbey Road. In other words, Ringo Starr has spent a lot of time as a punchline. A fond, gentle punchline maybe, but suffice to say he has long commanded the least esteem of the group; the consensus least-fab of the Fab Four. The Beatles: Get Back beautifully dispels the notion that Ringo Starr was in any way superfluous to the success of the monumentally talented group he was in. In the opening montage, Jackson reminds us that the band was thrilled to have Ringo Starr come aboard. They brought Ringo in upon their triumphant return from Hamburg to their home of Liverpool. They brought him in because he was the most beloved, celebrated drummer in the whole city. But beyond his skillful playing, the picture of Ringo that emerges from Get Back is of the most humble, sweet, well-humored, attentive and selfless musical collaborator one could ever hope to work with. It’s there in the way George Harrison chipperly exclaims “Hey Ringo” when he arrives early to find the dear man already in the studio. It’s Paul’s girlfriend, Linda Eastman saying she feels completely relaxed around Ringo Starr. It’s the fact that literally everyone is relaxed around Ringo (even the famously difficult Peter Sellers, for God’s sake) and the implication that his calming presence may have kept the band from splitting apart at the seams during that last month. His sweet demeanor and gift for really listening to people was probably crucial in creating the harmony needed for the lads to make those last two masterworks. In its kind, non-judgmental approach, Jackson’s film reels most possessed by the spirit of Ringo Starr. And that’s not just a nice revelation for the film to make. It’s also crucial to its exploration of the musical process as something not so linear, not so simple to get right. Get Back is a film about music, but also about all the vital intangibles that go into making great music. The cups of tea and cigarettes and the day Linda’s 7-year old daughter comes in and gives everyone’s spirits a boost. And there, seated behind the hit-hats and snares, is the greatest intangible of them all. “The Greatest Intangible of Them All” sounds like a joke he could have made at his own expense in Hard Day’s Night, but it’s absolutely true. The most important intangible in this whole documentary is the man who exudes empathy and positive vibes from his every pore. The one who can always give you some peace of mind when it’s in short supply. And when he’s done quietly grounding the egos and brightening the mood and blowing away the anxieties like puffs of smoke, he still knows how to play a mean kit. Liverpool’s favorite son. Whenever he gets to Heaven, there’ll be an octopus’s garden waiting for him.