Full disclosure: this is the first time an Indian film has topped one of my year-end lists. Even fuller disclosure: this is the first time an Indian film has made it on to one of my year-end lists, period. Fullest disclosure: I need to watch a lot more Indian cinema. S.S. Rajamouli’s impossibly thrilling rebel yell of an action drama is here at the top because it does just about everything (maybe not the Indian nationalist hat-tipping so much) absolutely right. It does stunts and battle choreography so daringly that James Cameron himself has asked Rajamouli to come make movies in the States where he can hopefully teach Hollywood about all the things its action movies have been lacking: dazzling color, coherent movement, characters we can really care about. RRR also does things right that I didn’t know you could do right, like a man swinging a revving motorcycle above his head and into a murderous colonizer. It does stirring drama right. It does developing friendships right. It does goofy humor right. My goodness, does it ever do music right. It dances right and moves right and, much like its two dashing mega-stars, it never fails to look incredible while doing it. For really, what is the point of action and spectacle that do not actively delight the senses? And, in addition to doing so much right as a pure cinematic showstopper, it manages to get story structure incredibly right too. It’s the kind of film where a giant smile spreads across your face because you realize what firm narrative hands you’re in. The movie where people use mopeds and wild animals as weapons also has a perfect grasp of how to build a plot. It introduces ideas and motifs to bring them back later. It has characters that grow in interesting ways (Not its white British characters, but that’s by design). It even manages to be the last film I can remember to make perfect use of flashback. My favorite user of flashbacks might be Quentin Tarantino because he never just uses them decoratively. In his films, cutting to a scene (or multiple scenes) in the past tends to happen when it is absolutley necessary to move the story forward. Pulp Fiction flashes back to Vincent Vega’s date with Mia Wallace (and her near-fatal overdose on his drugs) before we see him miraculously survive his encounter with the gunman because we need to see that dodging those bullets is not the first time Vince has been spared from doom. We must realize his fatal flaw: he wastes second chances, callously and repeatedly until it’s too late. And we must momentarily go back in time in Tarantino’s Kill Bill: Volume 2 to see the heroine’s training because there is no other way it makes sense for her to escape from a buried coffin. The only menas of salvation is to be found in the past. In RRR, Rajamouli goes back in time because its two protagonists have gone as seemingly far as they can go together. We see a terrible dead end for them and their friendship, until master showman S.S. Rajamouli holds up his finger and says, “Wait, wait, let me go back.” It occurs some 90 minutes in (Halfway through) and I grinned in awe of it. For about the twentieth time in the span of an hour and a half, I was putty in the Indian maestro’s hands.

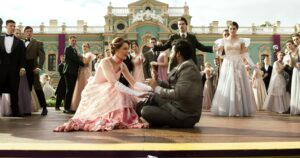

RRR is 2022’s boldest act of historical revisionism. It imagines a fateful meeting between two 1920’s revolutionary, anti-colonial Indian heroes (a meeting that sadly never came to pass in the drab real world): Alluri Sitarama Raja and Komoram Bheem. India is still almost three decades away from being free of the occupying British Raj, which brutalized Indians and reduced them to second class citizens in their own nation. That’s a historical fact and I want to note it so we can dispense with facts for the rest of this review. S.S. Rajamouli is not particularly concerned with them. RRR is an emotionally true action adventure, but it has very little interest in begin slavish to any historical record. It is about the imagined paths its protagonists take toward freedom. On protagonist, Komoram Bheem (played by a commanding N.T. Rama Rao, Jr., one of Telugu cinema’s biggest movie stars), is enlisted by his mountain village to use all his mighty strength to rescue a young girl who has been kidnapped by the cruel Governor of Delhi, as a captive plaything for his malicious wife. The other protagonist is Bheem’s secret adversary, Sita Raju, a local constable with the British police who has repeatedly been denied a well-deserved promotion (even after beating back a rowdy mob single-handedly with nothing but a club) for white supremacist reasons. His one way to secure a higher post among the same people who look down on him is to go undercover and take Bheem down before he can complete his rescue mission. Both men, as quickly becomes clear, possess god-like strength and intelligence. Rajamouli spends a good forty minutes just setting up his two leads’ might (and setting up the beginnings of his gloriously elaborate plot) before Bheem and Raju even meet. This finally happens when they team up to rescue a child from a train crash in a fiery river. And then the two become fast friends and the already high octane RRR ignites into an even higher gear of spectacle, music, action and emotion; one which makes every other 2022 film feel just a little ordinary. It’s like India’s answer to Face Off, if Cage and Travolta didn’t know they were enemies, but also it’s nothing like Face Off. For RRR is nothing quite like anything but itself. It’s a delectably colorful action musical about standing up to fascism, fueled by the power of male friendship. I will not spoil what happens when the two men learn each others’ true identities, but I will say that RRR is not the kind of film you try to predict. If any moment happens to play into your expectations (and that is a mighty big if), the next ten moments most decidedly will not. RRR is 2022’s best film because the year was all about gleefully unhinged imagination and RRR has fifty times more of it than any other film. It also has fifty times more emotion than the average film, fifty times more clobbered British colonialists, and is the only film in memory where a man outmuscles a giant time. Less is often more, but RRR is an exception. More has never been more than it was in 2022.

RRR has some of the best original songs to be composed for a motion picture (courtesy of the deservingly Oscared M.M. Keeravani) in many years. It is driven along by a clutch of brilliantly energizing songs (even it’s inspirational ballad comes with an adrenaline chaser) and by a no less enthralling score. Also, like so many great films, it just feels like a piece of music for the senses. It is not only marvelous to look at but to feel. It’s marvelous to watch it all hurtle past you. That’s the reason its three-plus hours zoom by so incomprehensibly fast. It rarely takes breaks. It is the reason I watched the film seven times in 2022 and would happily watch it again this very instant. Even writing a review for it feels exhilarating and breezy. I’m half-tempted to rile up the category purists and submit the entirety of RRR as my favorite song of its year. Rajamouli’s whirlwind masterpiece is set to gorgeous Indian music, but it has the resilient, unkillable spirit of a punk song. Under the fun and flash, this is a film about and for people who had to survive decades under a murderous settler regime. The subtext could not be more dour, but RRR has no time to mourn. It’s only thought is to fight bigotry and violent ignorance with a great, joyful noise. It’s the noise that got audience members dancing in the aisles. It’s the jubilant shout that has made it travel across the Indian and Pacific Oceans to new audiences, where it has resonated and nested in human spirits the world over. It’s why its almost comically stuffed plot (one that never stops moving) never feels tedious or exhausting. Because, even if your head swims from all the incidents and twists, your feet never stop tapping to it. The melody of it has you in its thrall, and if you don’t catch all the lyrics the first time, you’ll be alright. That’s what playback buttons are for.

RRR is a breathtakingly fun film and also an undeniably transporting experience. It fills you with the same life-affirming energy that powers the film, an unlikely, bizarre and perfectly calibrated mixture of laughter, joy, astonishment, righteous justice and tender emotion. It also, in a way that is not nearly as hyperbolic as it sounds, makes you feel like you can fly. It is simply one of the greatest super hero movies ever made, and indisputably the greatest not to have a comic book as its source material. Its two leads can leap high into the air like wuxia wire performers. They can outrace wild beasts and fight off hundreds of attackers by themselves. Beyond mere speed and strength, our two heroes have reflexes and senses of perception that would make Spiderman jealous. They are superhuman in might, intelligence and, most of all, heart. They are powered by the integrity of their emotions, and I think that’s very much a point Rajamouli is getting at. What his immersive direction accomplishes goes well beyond just capturing some of the greatest super-powered set pieces in cinema history. His aim is not just to show you great power but to make you feel like you are mighty too. For all the gobsmackingly kinetic fun on screen for these three perfect hours, RRR is driven by a sneaky intelligence in how it actually tries to empower us. The takeaway for me is that virtues like courage in the face of hate, resistance to oppression, empathy for other human beings and true friendship are the gateways to being a super hero in this world. These things make us stronger, even if we still can’t lift cars over our heads. There is a scene where one of the men is tortured, but Rajamouli uses music and nimble editing to undercut the horror and pain. He is giving his audience the fight of feeling what it is like to not fear the cruelty and violence of unjust actors. Mel Gibson’s William Wallace famously refuses the drug that would make his torture bearable, but Rajamouli gives that drug to us in cinematic form. He is enlisting the viewer as honorary superheroes along with Bheem and Raju. RRR is a film to make you feel mighty, triumphant and free. Standing up for the marginalized and the beaten down is atonic for our weaknesses. Fighting for our friends and what we believe in is enough to make us superheroes. Super hero films have gone to a lot of heady and rich places in the past. But when it comes to capturing what it feels like to be heroic and powerful, RRR sets a benchmark that will likely never be rivaled.

RRR is my favorite film of 2022, but it’s also the best representative of a year when maximalism came back to clear its good name. A year that gave us a four-hankie gonzo immigrant action film, a Jaws-evoking creature feature with Western vibes, and an Avatar sequel that spent its middle act as the most dazzlingly grandiose kind of hangout movie. 2022 was full of subtle, complex works but it also brought us back to the infections joys of being blown away by grand spectacle. Films like these asked us why we wouldn’t want our movies to go a little overboard. A film like RRR brings back the memory of those old Hollywood adventures. You’ll laugh, you’ll cry. It is a true extravaganza in an age where the majority of big tentpole movies are the furthest thing from extravagant. It delights in inundating us with emotions of every color, in overwhelming our senses, and in zig-zagging around our expectations. It is 2022’s most delightful movie. A zany, spinning, Tasmanian Devil of inventive motion and spontaneous storytelling. It packs more wild plot turns into any ten minute span than most directors manage to in an entire film. It knows we will be spent but profoundly happy by the end, grinning with elated exhaustion. This is what a cinematic rollercoaster should really feel like. RRR also, in a way no film has since Mad Max: Fury Road, has total faith in our ability to keep up with it. To keep up with a relentless deluge of action and narrative. It aims not only to please but to stimulate. I left feeling like my brain had been taken out on a jog for the first time in years. I was ready to collapse from sensory fatigue, but I was also seized by the desire to sit up and marinate in the pleasure it made me feel. Its final reel is a half hour of carefully placed dominoes tumbling in vibrant patterns. In every minute of RRR, you sens how much S.S. Rajamouli wants to make you smile and cry and marvel and feel. And no, displaying the most effort is not usually the way to get me on board with a film. Some directors (the Inarritus of the world) have a way of using hyperactive craft to compensate for a lack of ideas. But RRR is swimming with empathetic, righteous, revolutionary ideas, and that gives it all the license it needs to show off. Sometimes it’s just nice to feel how much an artist cares about the quality of their work. It’s no wonder Rajamouli takes part in his film’s effervescent end credits dance sequence. By the end, he can’t hide that he’s every bit as invigorated by what he’s made as the people watching it are.

In 2022, a number of directors revealed their top ten films, as a way of showing some of the votes that went into the latest Sight and Sound list (the all-important list of the 500 best films, complied every ten years by some of cinema’s most respected artists). Rajamouli was asked to participate and his list was met with some confusion. It didn’t have perpetual top picks like Vertigo, Citizen Kane, The Searchers, or The Godfather. Nor was it populated with more outre acclaimed films. There was no Chris Marker, Andrei Tarkovsky or Jean-Luc Godard. What was there were a few animated films (Aladdin, The Lion King and Kung Fu Panda), Spielberg’s historical action smash Raiders of the Lost Ark, Ben-Hur, Quentin Tarantino’s revisionist history revenge hit Django Unchained, and two wildly inaccurate historical action epics from Mel Gibson (Braveheart and Apocalypto). I’m not going to say that most of these would get anywhere near my all-time list, though I do at least very much like all of them. But I felt like many of Rajamouli’s supposedly left field choices fit the man whose movie I’d just watched and loved. They made sense coming from the director of RRR. Many of them are grand, emotionally gripping spectacles filled with action and big emotions. And I think, most importantly, the majority of them play fast and loose with history. Like Rajamouli (whose RRR unites two martyrs who never met and allows them to live as virtual gods), most of these movies are not simple recreations of history but could more accurately be called vivid dreams inspired by history. William Wallace didn’t do most of what Braveheart shows him doing but that’s completely immaterial to Rajamouli. Because Braveheart rouses and inspires and makes us think about how great it is to be free. Accuracy has nothing to do with its true mission. I can imagine Rajamouli’s defense. If a film stands for freedom and courage and selfless sacrifice and it also entertains the daylights out of you, why would you get hung up on something as banal as what did or did not happen? Movies are more than that. Scoff at Rajamouli’s picks all you want, but I see them as the DNA of a director who regards history as a toy chest. History is chock full of vital, staggering and entertaining stories to tell. And the creative possibilities become even greater when we dare to shoot history in fantastic Technicolor. What stories we can tell once we let ourselves dream of something greater than the basic facts.