James Gray is a director of eclectic sensibilities. So even though his latest gem is set in the 1980s and mostly makes use of golden age hip hop and Clash-style punk for its soundtrack, I’m sure he wouldn’t mind me busting out a little 90’s skate punk as a jumping off point for digging into his film. I enjoy the band NOFX quite a bit, in all their goofy, major chord glory. I am particularly fond of their 23-minute opus “The Decline”, a fiery, tonally diverse suite song that calls out the evils of everything from gun violence to anti-intellectualism to draconian marijuana laws. But its central thesis critiques a certain kind of myopic selfishness that feeds on fear. It’s the kind of frightened covetousness that turns garden variety self-interest into an all-consuming blaze of egomaniacal survivalism. One which transforms “my family comes first” into “my family comes only”. The idea that we only have the resources to care for our own, regardless of the consequences of that mindset. In the song’s rousingly cynical closing act, the learned emeritus Fat Mike roars out, “Fellow members, Club We’ve Got Ours. I’d like to introduce you to our host. He’s got his. And I’ve got mine. Meet the Decline.” This sprawling punk anthem came back to me as I watched James Gray’s autobiographical account of liberal New York Jewish family negotiating and painfully compromising their principles at the dawn of Ronald Reagan’s first term. Gray’s story is one of 2022’s most intellectually rigorous and deeply disquieting films because the people it most strongly takes to task are basically decent. The powerful advocates of classism and racism are mostly tucked away in the shadows and unseen. Gray alludes to the unscrupulous and the powerful intermittently (particularly by using the 1980 Presidential election as a loose framing device), but Armageddon Time is really the story of people who want to do the right thing. It is about people who want to be seen as compassionate but find themselves tripped up by the hurdles of prejudice, opportunism, generational trauma and moral cowardice. It is a potent and dismaying look at how American society prioritizes some people while stigmatizing others, and how even the well-meaning can be separated from their morals by the strong paternal hand of that society.

It’s the autumn of 1980 in New York City and a good-hearted but headstrong young Jewish boy named Paul Graff has just begun the sixth grade. Paul dreams of being an artist but his talent gets him sent to the blackboard on the first day when he draws a (quite good) rendering of his balding teacher. He doesn’t have to suffer his punishment alone for long, however, because another student all but volunteers to be punished with him. The teacher calls out the name of a young black boy, Johnny Davis. “The name’s Bond. James Bond”, the charismatic youngster suavely replies. They win their classmates’ laughter together and lose the right to participate in gym exercises for the day. Paul walks Johnny to his bus (Johnny lives in a poor neighborhood with only his grandmother) and they chat. They talk about Johnny’s dream of being an astronaut and the upcoming class trip to the Guggenheim Museum. Paul promises to pinch a 20-dollar bill from his mother’s purse so Johnny can afford to go on the outing. Paul lives a comfortable life, though his father (Jeremy Strong, strong) labors as a working class repairman. His maternal grandparents are wealthy enough to help the family. His older brother attends a rich private school downtown. His mother (Anne Hathaway, as great as I’ve seen her in quite some time) is a driven woman with plans to run for head of the District School Board. They live in a well-kept townhouse. Paul is especially close with his British-Ukrainian grandfather on his mother’s side, Aaron (an endearing and superb Anthony Hopkins giving one of the year’s truly great supporting performances). Aaron is a noble and doting man, always giving the Graff sons gifts and encouragement. He represents the very best angels of the Graff family, but even he has a somewhat stifling sense of familial tightness. He has known scarcity and hardship and a certain greedy fearfulness vibrates just below his genteel surface. His own Ukrainian mother saw her parents murdered by anti-Semitic hooligans. That was when she moved the family away from the Ukraine to Liverpool and from there across the ocean to New York City. The Graffs have had to fight prejudice and hate to become the modestly successful American family they are and they live with the uneasy feeling that it all could be taken away from them in an instant. That is why, when Paul’s blossoming friendship with Johnny lands him a suspension (they are both caught smoking pot in the stalls), even kindly Aaron supports the decision to pull him out of public school and send him to the lofty, elite school his older brother attends. Paul is being pulled in two directions by his close bond with a nice, misunderstood black boy and by the many forces that want to groom him into the thing that Johnny will never be allowed to be: a powerful, accepted cog in society’s upper echelons. The private school does not settle the war for Paul’s soul, it only starts it. It does not conclude the matter of Paul’s affluent future as his family hopes. Instead, the whole ordeal and especially his painful separation form Johnny opens Paul’s eyes to ugly and systemically violent truths about the American Dream and which people are handpicked to take part in it. Moreover, it sets in motion a tragedy that irrevocably changes these characters and alters the destiny of the man directing this film.

James Gray is much too eclectic of an auteur to be hemmed in by the kinds of stories he tells. He’s one of the last directors you could ever pigeonhole. He has been back to the turn of the century (The Immigrant and his masterpiece The Lost City of Z), into the future (Ad Astra) and occasionally to the present (Little Odessa and Two Lovers). His films have gone to Edwardian England, the remote Amazon, the far reaches of outer space and frequently returned home to his native New York City. If there’s a germ of a consistent theme to be found in his work, I think it’s the heavy yoke of family and expectations. In Ad Astra, Brad Pitt’s astronaut sets out to find a father whose approval he has always craved, while that same father has suddenly cast off a lifetime of societal expectations by going rogue. The Lost City of Z‘s Percy Fawcett starts as a social striver trying to clear his tainted family name before a chance to make good by mapping the Amazon points him down a path that is his alone. But while he loses himself in his beloved rainforest, the question that looms is whether he is doing right by his family back in England. Family and society are primal forces to either surrender to or rebel against but, no matter what, you can never entirely get away from them. Not even light years away from Earth. They are fundamental fields of gravity that govern life as James Gray sees it and all of us define ourselves, rebel and conformist alike, by how we respond to them. In Armageddon Time, Gray renders the vision of his own family with fairness and empathy but also with merciless honesty. Family can be an unflattering thing; poison and antidote in one bottle. He shows the Graffs’ fearful selfishness, their blind entitlement, their internalized racism, their years of suffering anti-Jewish bigotry now unthinkingly projected out at the next marginalized group. He captures a brutal beating at the hands of his stern, emotionally repressed father. If Avatar: The Way of Water posits that family is a fortress, Armageddon Time adds that it can be a fortress under siege with us trapped inside of it. Family can protect us but it also has the power to suffocate and drive us mad. The entire institution of family carries with it the uncomfortable notion that our empathy is already partly spoken for, that we reserve a larger portion of our kindness and care for this one group of people that shares our genes. Armageddon Time is James Gray’s gently harrowing account of learning that opportunity and dignity are not apportioned equally in America. The brilliance of Gray’s film is in how he sees family as a snapshot of that harsh societal truth in miniature.

Armageddon Time is about as insightful a film about white privilege as I have ever laid eyes on. What makes it so biting is how it sees racism and privilege as the result of both deliberate cruelty and unconscious self-obsession. I was reminded of something Brad Dourif’s doctor from Deadwood says: “I see as much misery out of them moving to justify their selves as them that set out to do harm.” A society of racial injustice and unequal opportunity is built a brick at a time by the justifications of individuals afraid for their own position; by those who fear that they only have enough capacity (of money, of time, of emotional energy) to see to themselves and their own circle. The gravitational pull of self-interest is hard to resist. Fat Mike has it right. He’s got his and I’ve got mine. The Graffs are basically well-meaning people. They do not espouse hateful rhetoric, even if they do fall right into prejudiced line the second one black boy’s existence poses some vague threat to their child’s future. There is an unspoken theme in Armageddon Time about how people act out their own past oppression against other exploited groups, passing their victimization along like a hot potato. The Graff family is vocally against Ronald Reagan but they are blithe participants in the society that is about to welcome Reaganism’s self-serving myopia with open arms. They may be registered as Democrats but they eagerly push Paul into a school and career track populated by the sons of the greedy, powerful and unprincipled. Many, this critic included, are perfectly willing to attack a system solely interested in securing prosperity and safety for a privileged handful of whites, but it takes a different sort of courage to disavow the benefits we receive from that system. To refuse what you are given and let your advantage go unused. Armageddon Time understands how hard it is for ostensibly progressive white people to refuse the money, so to speak, even when we know it has been stolen from the disadvantaged. We can critique the unjust enrichment of white over black all day long, but there is a tendency to do so in a very generalized way; a way that leaves our own selves out of the problem. The Graffs know things shouldn’t be the way they are, but they also feel they could really use any leg up that America is offering them. Even the noble and tolerant grandfather Aaron won’t say no to this arbitrary fortune. He accepts special treatment and remembers how recently the shoe was on the other foot. How not very long ago it would have been a Cossack’s boot breaking down their door. “The system is rigged and unfair,” we cry out and then discreetly drop the tainted coins into our pockets.

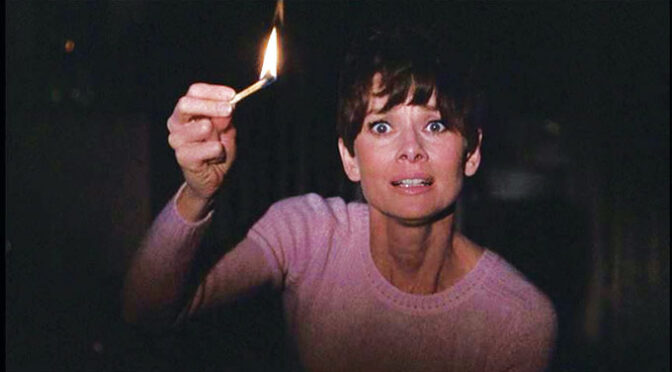

Armageddon Time is an intimately observed coming of age story for James Gray but it also has the foreboding of a slowly unfurling horror movie. The slasher waiting in the bushes is nothing less than the American 80s, and nobody’s ideals or best liberal intentions are safe. Gray’s wise, sober little tale has the clammy panic of a waking nightmare. The more Paul watches all of society degrade and devalue Johnny (from uncaring teachers who write him off to the police to even other black adolescents), the more incensed Paul becomes. That’s when the world starts to take on truly chilling undertones. Because he learns that all his righteous indignation, disgust and sorrow can’t give him the courage to really do anything about this injustice. The Armageddon in question is the total paralysis of human empathy and social action; the failure of our own convictions when we have to make a choice that might threaten our own interests. Meanwhile, Johnny Davis knows where his story is headed from the beginning. His resigned, worn out face tells us everything we need to know. He is heartbreakingly aware that no future has been set aside for him. When Paul worries about his teacher punishing them for ditching a field trip, Johnny chuckles knowingly and says, “Nothing’s gonna happen to you, man.” Johnny has Paul’s back with a tender ferocity. He doesn’t have a chance against this depraved system, but it hurts him to see it grind down his friend. Paul sadly finds himself tongue-tied when two rich classmates at his new school ask him if he ever went to school with blacks (but of course they don’t use the word “blacks”). The Graffs watch a Reagan interview where the incoming President warns that this generation might be the one to usher in Armageddon. His Armageddon is a rhetorical weapon, a fear cudgel that he will soon use to help herd America into a notoriously conformist chapter of its history. The true Armageddon isn’t what Reagan says it is but, in getting the American populace to buy into the idea, it does become a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. The real cataclysm is the wilting of the American soul in the face of manufactured fear. The compromising of Americans’ principles as more of them prioritize their financial security and make peace with the limits of their power to help the stigmatized, brutalized and neglected. Sometimes that racist abuse takes the form of plain old neglect. When Paul is sent to the principal’s office, the principal doesn’t know what to do with him and sends him right back to class. The message is actually crueler than mere punishment. Society has repeatedly let Paul know that it doesn’t much care where he goes or what happens to him, just that there’s no real place for him. He simply doesn’t matter. I have heard and digested the criticisms of Armageddon Time as being just another exercise in white guilt. But I find James Gray’s self-immolating autobiography so clear-eyed and scorching that it avoids navel-gazing. It never feels like an act of indulgent self-flagellation or pat forgiveness. Certainly not forgiveness of any kind. It sees the human beings at the center of this story in all their dimensions, but it never lets a one of them off the hook. Under its muted, autumnal visual palette, Armageddon Time breathes a rebuking fire that consumes Gray’s loved ones and himself.

The problem Armageddon Time sees is how the future is forever being held back by the past. The way that, even if you were to assemble enough people who genuinely want to create a more equal and equitable world, they would need to sacrifice personally. They would need to agree to break with traditions that have protected and enriched them. Real justice would require drastic change, and whoever created the system as it currently stands was cunning enough to entangle a lot of white Americans in it; to make sure that each of them has enough of a piddling token stake in the status quo that they feel they would suffer some detriment from altering it. In the way it sees the morass of self-interest and complacency as the enemy of progress, Armageddon Time reminded me of The Wire, David Simon’s revelatory show about law, crime and city politics in Baltimore. Various characters in that show envision and try to implement better, fairer ways of governing and policing. Better ways of being as a society. And the stark brick wall reality that they always butt up against is that it’s very difficult to get people to change an unjust system that they own shares in. If only half the people in that system didn’t want to be judges and higher-ups, The Wire‘s unorthodox Detective McNulty laments. “But no, everybody stays friends. Everybody gets paid. And everybody has a fucking future.” It’s just what Paul Graff’s family is doing when they place him in that private academy full of future judges, politicians and CEOs. They are buying him into that safe future that is so very beholden to the craven past. In what could have been too on the nose, the first person Paul runs into on his first day at rich school is Donald Trump’s father, Fred Trump. He is there with his daughter Maryanne Trump Barry, an Assistant United States Attorney. She has come to the school’s assembly to tell this auditorium full of privileged white boys the unvarnished truth. The future has been prepared specially in advance for them. It has been paid for and gift wrapped to be given to them on a day not so far from today, in a year not so distant from 1980. It is of course expected that they will one day reciprocate for their own kind, ensuring that the right to peace and prosperity is handed down to the chosen people who will gather in this same stately hall decades from now. Armageddon Time does not actually get its title from that Reagan interview. It’s instead a reference to “Armagideon Time”, a 1970s reggae song by a black Jamaican named Willie Williams. It was later covered by a white British band called The Clash. The song is about poverty and inequality and fighting back against systemic evils. There is not much hope in Armageddon Time outside of a small moment of symbolic victory for Paul. But there may be a nugget of hope in the lyrics of “Armagideon Time”, a reminder of what needs to be done. “A lot of people won’t get no justice tonight,” Williams sings. “Remember to kick it over.”

The major reason Ratatouille‘s Anton Ego is so many critics’ favorite depiction of a critic (other than the dream of having a velvety Peter O’Toole voice) is that he shows how much we all want to love the things we take in. Beneath his imposing veneer lies the soft heart of a man who wants to be completely bowled over by a piece of art. It may not always work out that way, but no self-respecting critic wants to find a piece of art mediocre or bad. Lovers of art want to have a reason to love even more art and, even if we feel reasonably certain that a given film is going to disappoint us, we still hold to the hope that maybe it won’t. True film critics start every film hoping, praying to be surprised. And when that happens, there are precious few experiences more rejuvenating and magical. I never disliked James Cameron’s 2009 world-beater Avatar. Not by a long shot. I always though it was pretty good and I still basically feel that way. Its environmentalist message is definitely earnest and cheesy (even if pitched entirely to my viewpoint), but earnestness has never been the Cameron trait that bothers me. Obviously the visuals were and are staggering. But the visionary director’s nakedly sentimental action extravaganza never hit me with the emotional intensity of Cameron masterworks like Terminator 2: Judgement Day, Aliens or Titanic. It wasn’t that Avatar was dopey, because of course it was. It’s not like Cameron has ever been particularly script-focused to begin with. His plots and characters deserve a lot of praise, but he’s the furthest thing from writerly or subtle. Maybe it was just that the 2009 Avatar‘s New-Agey ideas felt too borrowed and obvious, even for someone as broad as Cameron. It was as if he had just registered for Facebook and stumbled on a cache of well-meaning but hackneyed climate change memes that he couldn’t wait to share. Avatar was far too committed and sincere for me to ever call it phoned in. It clearly came from a place of great conviction on Cameron’s part. But maybe its ham-handed message and those well-worn tropes so many made fun of it for (the comparisons to Dances With Wolves and Pocahontas) pointed toward something just a little less personal about it. Even True Lies feels more suffused with Big Jim Cameron’s heart and personality, what with its goofy divorced guy energy. I like Avatar fine in a way where I was content to never talk about it or even watch it again. Unlike so much of the movie-watching world, I did not have a pressing need to “return to Pandora”. So. all of that to say, Avatar: The Way of Water being even pretty good would have been a splendid surprise for this one-time Navi agnostic. But what I ended up getting from the second Avatar was well above and beyond anything I could have hoped for. And I could break it all down into a numerical grade and put caveats and qualifiers on my praise but, to tell you the truth, I don’t feel like it. A film as elating as this leaves a critic too satisfied for hedging or hair-splitting. After a three-hour bath in Cameron’s aquamarine wonderland, quibbling is the furthest thing from my mind. I am surprised and delighted to tell you that I unabashedly loved Avatar: The Way of Water.

Avatar: The Way of Water picks up some 16 years after the first one. After fending off his own military from decimating the forests of Pandora for precious metals, former paraplegic Earth Marine Jake Sully (Sam Worthington, shaking off the stiffness of his first outing with Cameron and giving what I can happily call a tremendously good performance) is now living in domestic bliss with his Navi warrior wife Neytiri (Zoe Saldana, as reliably strong here as she always is) and their four children. This includes their two teenaged songs, responsible eldest son Neteyam (Jamie Flatters) and their second eldest, the more impetuous and eager Loak (Britain Dalton). They also have an adopted teenage daughter named Kiri. Kiri (marvelously played with a Winona Ryder-like blend of quirky innocence and rebelliousness by 71-year James Cameron muse Sigourney Weaver) was birthed by Earth scientist Grace (played briefly by Weaver without the use of mo-cap technology), who fell into a coma after one of the first movie’s battles. Kiri’s father remains unknown, though giddy speculation runs high among her siblings. The youngest Sully child is their 7-year old daughter Tuk (Trinity Bliss, adorable). The loving Sully clan has been enjoying a relatively uneventful decade-plus. Their season in the Sun ends when Earth ships suddenly arrive in a fiery blast, carrying a new wave of Sky People, as the Navi term the Earth interlopers. Cameron cuts to a year later with Jake, Neytiri and the rest of the Navi (including the Sully sons) fighting to stop the Earth forces from encroaching into their sacred forest. They are doing quite a good job of it too, which is why the military presence on Pandora has called for an upgrade to their forces. In an effort to help neutralize chosen warrior Jake Sully, the corporate and military interests of Earth have essentially brought back the first film’s villain, Colonel Quaritch (a very strong Steven Lang), nothwithstanding the fact that he expired with two arrows through the chest at the conclusion of the first Avatar. The film repeatedly reminds us, however, that this is not actually the same Colonel Quaritch but a kind of copy containing all of his data. In other words, Quaritch’s superiors shrewdly preserved his memories on a zip drive and have uploaded them into a nine-foot tall Navi body. The new Quaritch wants a chance for revenge against the turncoat Jake and against the Navi woman who violently dispatched the human Quaritch. The Earth forces on Pandora hope this personal vendetta (and the aid of Quaritch’s elite team of Marines, also brought back to life in avatar form) will turn the tides in their favor and give them the added push they need to neutralize the Forest Navi resistance. And, in the jam-packed first thirty minutes of Cameron’s three-hour epic, Quaritch and his grunts come close to succeeding, after they catch the Sully children snooping around the site of the first film’s final battle. Jake and Neytiri arrive just in time to rescue their kids and the whole Sully family escapes by the blue skin of their teeth. But Quaritch does take one prisoner: his own 16-year old son, Spider. Spider was only two at the time the Earthlings retreated all those years ago, and was too much of an infant to travel with them. As a result, he has become close with the Navi and fashioned himself as one of them, much like Jake once did but without being placed into a Navi avatar. The Sullys have all but adopted Spider. He is particularly close with thier actual adopted child Kiri. After their close call, the Sullys know the enemy is building its strength up again and that Jake’s hunted status could put their forest loved ones in mortal danger. Over the tearful protestations of his family, the regimented and disciplined Jake pressures them to leave their home. They must mount their dragon-like Ikran (let’s be honest, they’re dragons in all but name) and fly somewhere where they can hide from their would-be captors. And so ends 2022’s most gloriously stuffed and thrilling Act One. But the real business of Avatar: The Way of Water truly begins when the Sullys reach the film’s central destination: the turquoise waters of the far-off coastal islands. The lands that are home to an entirely distinct tribe called the Metkayina.

As Jake and his family are reluctantly taken in by the Metkayina leaders, Tonowari (a strong Cliff Curtis) and his pregnant warrior queen Ronal (Kate Winslet, giving just enough to make me excited to see her do more in the franchise’s next entry), something miraculous happens to the film. James Cameron, the dominant elder statesman of blockbusting action, creates something that feels different and new. If you’re coming to this review from my review on The Woman King, you may recognize a trend taking shape for 2022. The streak of unique action hybrids stays alive. Cameron has created what feels like history’s first true action hangout movie, certainly for an action movie of this enormous scope and budget. While the film is packed with some of the most exciting and blisteringly inventive action setpieces this side of Mad Max: Fury Road (or 2022’s own RRR, of course) Cameron also finds room for moments of beatific calm. I love almost every minute of The Way of Water, but my eyes lit up when I realized what its transcendent second act was doing. James Cameron has created an astoundingly beautiful underwater world for us to gaze at in childlike awe, and he’ll be damned if any action movie rules are going to get in the way of us taking it in. “You’ll get to spend the whole last hour with your heart in your trachea,” he says, “But I didn’t transport us all this way to an intergalactic tropical paradise to not have any downtime.” And by taking it all in, I mean really stopping to look at it and see how the characters themselves (especially starry-eyed budding naturalist Kiri) are moved by it. The first Avatar had lovely scenery but Cameron’s superior-on-every-level sequel goes further to give the natural beauty an emotional connection. It’s a small, perfectly judged decision. There’s an old cineaste’s proverb that says a great film teaches you how to watch it in its first moments. Cameron’s Metkayina villagers teach us how to watch the film roughly an hour in when they teach the Sully children how to hold their breath for longer underwater. “You must slow down your heartbeat,” the tribe leaders’ daughter Tsireya tells Loak. And the same applies to us. Exhilarating and brilliantly blocked scenes of combat and survival are coming soon in Avatar‘s glorious third act, but Cameron also wants his devoted, action-loving viewers to tune into the joys of his slow scenes. Not only because they are fantastic, but because those moments of serenity are going to make those deliriously smart action scenes leap off the screen more vividly when they arrive. The enraptured smiles on Kriki and Tuk’s faces should match our own and we should feel just as blown away by the film’s meditative wonder as by how kinetic it is. “Your heart is fast,” Tsireya softly admonishes her new pupils. When you allow yourself to experience both the film’s transcendent, gently euphoric lulls and its breathlessly paced, emotionally charged action highs in the way Cameron wants you to, the full experience of Avatar: The Way of Water becomes almost impossibly rich: fun, silly, sincere, empathetic, tense and heart-swelling. James Cameron put my heart and all my brain’s pleasure receptors in a delightful centrifuge and whirled them around until they surrendered to the sheer majestic glee.

Avatar: The Way of Water is also maybe the most thematically potent film James Cameron has made since Terminator 2: Judgement Day some thirty years ago. Like its predecessor, this Avatar is very much about respect for nature and environmental stewardship. Cameron is once again unembarrassed to bare his whole conservationist heart (and, unlike Adam McKay, he has nothing to be embarrassed about). In this film, Earth’s goal is no longer mining for precious metals but turning Pandora into a full-scale replacement Earth. Environmentalism is the core message but the film’s strongest theme is actually the power and complexity of the family unit. “Family is a fortress,” Jake Sully tells his loved ones. It may not outwardly seem like the most complex organizing idea for a film (then again, it is the major theme of Cameron’s two game-changing masterpieces, T2 and Aliens). The weaker Fast & Furious films are a reminder that having a character say the word “family” a lot does not automatically turn your action movie into interesting cinema. But Cameron threads the idea of family through his lushly heartfelt movie with disarming conviction. And with so much to love about the visuals, lovable characters (even agro-heel Quaritch gets a fresh new coat of humanism this time around), patient sense of tone and smart action directing, Cameron’s unfussy use of the family theme becomes one more beautiful, enriching element. It does something I did not expect after the first Avatar. It makes thee big goofy blue alien film feel genuinely sumptuous and even, dare I say, sophisticated. Maybe sophistication isn’t something you need from a blockbuster actioner like this, but it sent my appreciation through the roof and out past the Earth’s atmosphere. As in Titanic (with its themes of classism), Cameron is using theme in a very practical way. The pattern of families and duty to one’s own and how fathers and their children build trust is not deployed for any lofty cerebral purpose but simply to add depth to its characters and its plot stakes. It’s the way Cameron connects that theme very plainly and directly to every one of these characters, from the Sullys to Quaritch and Spider. It’s even tied to the space whales (I do apologize for taking so long to mention that there are kick-ass, hyper-intelligent whales in this beautiful gem). This is theme done in the unpretentious, no-bullshit James Cameron house style and I was unprepared for just how masterfully it would work on me.

Avatar: The Way of Water can also sit proudly with recent masterpieces like Once Upon A Time In Hollywood, The Fabelmans and The Irishman as films that are in conversation with their director’s soul and body of work. Just as surely as Martin Scorsese is drawn to crime and faith or Quentin Tarantino loves old B-movie theaters, James Cameron loves water. The old joke in the early Aughts was that he loved the sea so damned much we might just lose him to underwater documentaries forever. Water features heavily in Titanic and The Abyss, but even T2 introduces a villain who can essentially liquefy himself. It is that undulating watery power that makes the T1000 so terrifying (okay, he’s also indecently fast) and it is also only through melting that he can eventually be defeated. There’s a sort of impassive quality to water that can be both sword and shield and I think Cameron finds something beautiful and humbling about that. It is both karmic and frighteningly impartial. In Titanic, human greed may take sides but the icy waters of the North Atlantic do not. “Oh sure,” James Cameron might say to all my high-minded theorizing. “That’s partly it. But it also just looks incredible.” And he would be absolutely right on the money (he lives on the money). The third act of Avatar: The Way of Water, involving hostages and a giant whaling vessel, is astonishing and innovative and it is where James Cameron lets the titular H2O of his film fully out of its cage. It is where Cameron’s irresistibly rousing watery id rushes through every nook and cranny of his meticulously designed film. And, for as much as I adore the decision to have a meditative and peaceful second act, this technically more traditional action finale is what makes me fall completely in love with the film. A massive, action-heavy third act may seem more been-there-done-that, but James Cameron action finales are never standard and are never ever phoned in. What makes the film soar from start to finish is its unabashed emotionalism and I cannot name an action finale this side of RRR that feels more tied into emotion and character. I want to go watch that last hour again, this very instant. I hollered, laughed, and felt water welling up behind my eyes. Whatever remaining tolerance I had for the flat, dingy sky battles of so many modern action movies has been entirely rinsed out of my system. James Cameron has flushed them all down the drain in a whitewater torrent of tears and serotonin.

If I haven’t emphasized it properly, James Cameron has also made a very well-acted film here. The first Avatar didn’t attract too many performance hosannas outside of Zoe Saldana’s potent ferocity as Neytiri, but The Way of Water is filled with strong, fully dimensional acting. Sam Worthington’s work as Jake Sully is an extremely pleasant surprise. He has improved dramatically since his agreeably wooden work in the first Avatar (I think the more ensemble-y nature of Way of Water is good for his intermittently frustrating but generally sympathetic character). Saldana continues to be the franchise’s reliable heavyweight, a powder keg of feeling who can lend subtlety to big moments. The Sully sons are completely solid at worst, even if the eldest does verge on being an afterthought. Cliff Curtis and Kate Winslet lend gravitas to their Metkayina leaders. I think character actors’ character actor Steven Lang is doing superlative work as the film’s heavy, finding notes of humor, introspection and even self-doubt in the cocksure force of nature that is Quaritch. It’s also just nice to see that character get more to do than bark, seethe and glower. On second viewing, I have firmly decided that I actually like dread-headed white teenager Spider, the film’s most polarizing character for reasons that require no further explanation. But if I have to give out best in show, it absolutely belongs to septuagenarian and longtime Cameron collaborator Sigourney Weaver, whose wonderfully soulful work as the moony teenager Kiri is like some great Winona Ryder character discovered decades later. Cameron and Weaver broke boundaries back in 1988 when her commandingly brilliant work in Aliens became the first action performance ever nominated for an acting Oscar. And here they both are three decades later, still standing at the cutting edge of what action cinema can be. That two titans of the genre are here in this banner year with one of the very best films of the year is fitting and refreshing, if not the least bit surprising. If they do not have the literal best action film of 2022, that’s of no great concern. They are 2022’s action keynote speakers all the same.![]()