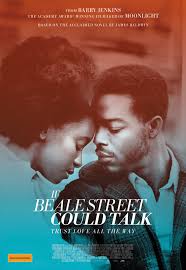

Barry Jenkins is three films into his young career and has already secured Oscars for two of his actors (Mahershala Ali and Regina King) and won a richly deserved Best Picture award for Moonlight. He got a reasonably priced life insurance for all of them. He’s a director of clear, remarkable insight into human emotion and he’s just getting started. To try and put my finger on what this voracious, cinema-loving visionary (an honor he has already amply earned) is about feels premature and kind of like a fool’s errand. A talent this smart and ambitious could pivot around my expectations at any moment. An auteur with his intelligence and restless imagination could take off in any number of new directions. Still, I feel like making a future fool of myself. So here’s what I see and adore right now in Barry Jenkins. He taps into the heady tingle of cerebral indie cinema, while also harnessing the rousing, operatic emotion of great melodrama. There’s a reason Moonlight managed to snag Best Picture away from a luscious, crowd-pleasing, heart-on-its-sleeve extravaganza like La La Land. As heady and intellectually rigorous as Moonlight is, it’s also a film that connects on a gut level. I had seen and loved the film and recommended it loudly. But I also tended to hedge my words, letting people know that this was a challenging piece of work. And both Moonlight and If Beale Street Could Talk certainly are challenging, daringly cerebral films, beyond any shadow of a doubt. But the friends I recommended Moonlight to didn’t come back confused or thrown off by its ideological rigor. Instead, they were all swept off their feet by its overwhelming emotion and stunningly realized characters. I had undersold just how much potent feeling Jenkins’ film had in it; a depth of emotion that you could feel even if you didn’t know the first thing about complex subjects like masculinity, queer sexuality, and African American identity. I’ve been good about rationing my sports analogies lately, so I’ll indulge myself here. Babe Ruth was one of the all-time greats not just because of the considerable power of his bat. He was also a skillful pitcher. Crushing a dinger and striking out a batter are two very different skills, and usually you’re lucky just to do one very well. Being great at both is a big deal. In film terms, the same is true of being able to craft a prickly, aesthetically daring tone poem and a heart-swelling, emotionally direct melodrama. Barry Jenkins is Ruth. He can do both. Films like Moonlight and If Beale Street Could Talk hold a whole host of deep social insights to dig into. But one need not do any digging to appreciate the vibrant characterization and powerful feelings of these films. Barry Jenkin’s second highly literary masterpiece on the subject of black identity in America may seem like it should be a daunting undertaking, but I dare anyone not to be utterly moved by what he has put on screen. His complex themes float along in a gentle current of pathos and lush empathy.

If Beale Street Could Talk moves like a gentle whirlpool. It’s not the least bit difficult to follow, but it does have something of an elliptical sensibility. It continually drifts through present and past and back to present again, feeding us new insights into its characters. The first thing we learn is that there are two black New Yorkers in the early 1970s, a man and a woman in their late teens, that they are very much in love, and that they have been separated. The young man, Fonny, (a subtle, soulful performance by Stephan James) has been imprisoned in Attica for a crime he didn’t commit. The young lady, Tich, (a lovely and breathlessly heartfelt debut by Kiki Layne) has just learned that she is pregnant with Fonny’s child. We will not circle back around to the reason for Fonny’s arrest (a mistaken rape accusation, likely fueled by improper suggestion from the police) until several scenes later. What Barry Jenkins wants us to see first is that these two young adults are in love and have been thrust apart. Before we come to learn the details of Fonny and Tich’s courtship and their lives together, we meet their families, played by an outstandingly nuanced ensemble of black actors. Regina King recently won an Oscar for her stirring work as Tich’s kind, resolute mother. Colman Domingo and Teyonah Paris are also nothing short of sublime as the father and older sister who complete Tich’s wonderfully supportive family. Fonny’s family is more tempestuous. His father (Michael Beach) is happy to hear a baby is coming, but Fonny’s dogmatically Christian mother (Aunjanue Ellis) and two stern sisters are outwardly critical of the situation and of Tich’s worth as a partner for their brother. The scene where the two families meet to learn of Tich’s pregnancy is a symphony of beautiful dialogue and perfectly played emotions; a torrent of harsh judgment and loving support, battering up against one another. We see the early days of Fonny and Tich’s romance, before Fonny’s incarceration, their struggles with racism, and their efforts to find an apartment together. In the present, Tich works at a perfume counter and stresses over Fonny’s trial. The District Attorney has given the rap victim money to return to her homeland of Puerto Rico and Tich’s mother, Sharon, makes plans to fly there to meet the poor woman face to face in the hopes of appealing to her sense of empathy. Beale Street has plenty of plot (a teenage pregnancy, a false arrest, the entire fraught racial backdrop of early 1970s America), and yet it’s not really about plot. Barry Jenkins, adapting a very literary and tonally rich novel by the brilliant James Baldwin, really had made a film that is about emotion; about their loved ones and their unwavering love for each other. Plot is what rudely interrupts that love. It is what harasses Fonny and Tish, separates them, and threatens them with force and fear. Barry Jenkins knows his way around a plot very well, but I believe this story is about love trying to withstand events and circumstances. When you are black in America, I imagine you dream of a day, a year, a life where very little happens to you.

And, for all its potent characterization, dazzling directorial flourishes, and intoxicating tone, If Beale Street Could Talk really is just a simple story of two people who want to love each other and create a life together. It’s the simple story of a humble dream that gets cruelly and needlessly complicated by the hateful forces around it. James Baldwin was one of the 20th century’s most marvelous and eloquent minds, a contemporary of social pioneers like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. As a black man, he saw the American Dream in all its idealistic beauty and ugly hypocrisy. He saw that this Dream meant something different if you were born with a darker skin tone. Barry Jenkins taps into Baldwin’s vision seamlessly. His film is a glorious piece of New York City Americana, seen through a glass darkly. Even though the film is set in the early 1970s, the New York City captured in it feels like a luminous visions of its 1960s self here: diverse, vibrant, and buzzing with intellectual energy. Nicholas Britell’s incredible channels evokes New York as both a dream and a gritty nightmare; George Gershwin and shadowy back alleys. The vision Barry Jenkins casts upon the screen is the New York City of Paul Simon songs, poetic, thoughtful and curious. And yet, for all its beautiful enlightenment, it is also the place where a bigoted police officer can harass an innocent black couple without fear of losing his job. In one of the film’s most indelible scenes, Fonny brings home an old friend who has just been released after two years in prison. This man (played by the great Brian Tyree Henry, completing a superb trifecta along with his work in Widows and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse) is a goofy and gregarious sort, but the smile vanishes from his face when the subject turns to being behind bars. This is the film’s struggle in miniature. This man’s inner light seems naturally bright, but he has been put something through it that causes that light to flicker and dim. Beale Street is about trying to maintain positivity and humanity in a society that wants to take it from you. And this dark truth doesn’t mean that there is no American Dream at all, but just that it is inherently complex. It has been a complex and somewhat hypocritical thing since its very outset, when the founding document held its tongue about slavery while simultaneously laying down the rhetoric that would eventually underscore its abolition. If Beale Street Could Talk is a very romantic film, and not just in terms of its love story. It is romantic about the full possibilities of American life. James Baldwin and Barry Jenkins are both curious to live in a land of beautiful ideals and rich possibilities, while having that same egalitarian place throw ignorance and hostility at you. What kind of land can create the Bill of Rights and Jim Crow laws? A beautiful land. A disturbing land. A land that has always held a great turmoil in its soul.

The wonderful paradox of If Beale Street Could Talk is that it can hold such painful truths in its heart while never feeling cynical or defeated. It can do this because its main ingredient and overarching theme is love. Love is the fortress that steels Tish’s resolve to fight for Fonny and to carry their child and to persevere without him while he is gone. It’s what keeps Fonny sane amid the horror he has to endure inside Attica. In a way that doesn’t cheapen or minimize the strife these characters and so many others like them face, the film quietly maintains that love will see them through this. When Tish is wracked with despair and self-doubt, her mother softly and fervently reminds her to trust love. “Trust it all the way,” she says. If Beale Street Could Talk sees love and community as succor and salvation for black Americans like Tish and Fonny. Love is not just there shield and refuge, but something very active. It is Tish’s sister fearlessly defending her when Fonny’s sisters try to belittle her telling her to unbow her head when she feels ashamed. It is Tish’s mother flying to Puerto Rico on the slim chance it will help Fonny beat his case. It is Tish’s father selling goods on the black market to raise money for a lawyer. When Fonny’s father frets over how he will pay for his son’s defense, Tish’s father tells him not to worry about the money. Money is not where their strength comes from. Love for family will will the money into being. “You know some hustles. And I know some hustles. And these are our children.” Barry Jenkins journeys unafraid into America’s ugly past to confront the racism and injustice that has always lived here. And he does so with an incandescent torch of empathy and compassion. The woe in this story is never his focus. His film is about the very best in humanity and the unfortunate, petty and hateful bullshit that tries to tear it down. But darkness does not prevail here. Barry Jenkins, master humanist that he is, always keeps hate on the ropes.

If Beale Street Could Talk searches for that which is beautiful and it finds it in spades. It is not a film with what I would call an unambiguously happy conclusion, but it is gentle and honest. It is a story of immense struggle and of human beings finding their way through that struggle. When a society tries to take your life away, you prevail by staying alive and protecting the fire within yourself. You keep it going with more love, more kindness, more concern for one another. When systems of oppression try to deprive you of your humanity, you defy them by holding fast to it. James Baldwin and Barry Jenkins do not pretend for a moment that doing this is easy. They simply assert that humankind is beautiful, loving, and immeasurably strong. This film sees intolerance and suffering and it throws a fist upward in solidarity with anyone who is going through something trying. Even the rape victim who falsely accuses Fonny is treated with sympathy and respect. She too is going through something terrible, trying to maintain some dignity in life’s unforgiving storm. She is partly the source of our characters’ frustrations and setbacks, but she is trying her best to weather a terrible situation and she deserves our empathy. If Beale Street Could Talk feels like peaceful resistance rendered in celluloid form. It feels anguished and confused by any individual or system that would demean and devalue people, but it is incapable of that same hatred. Its response to hatred is to build a bonfire out of the most lovely, creative and humane things it can find and hold the darkness at bay. Shadows dance menacingly behind our characters and throw themselves in fleeting traces over their bodies, but they are no serious match. Beale Street’s emotional blaze burns with too much compassion and goodwill.

Beautiful, strong, pure feelings are the film’s anchor. They are the stable and calm center around which tis dizzying tone poem spins. I cannot stress how assured Barry Jenkins is at conjuring tone, at allowing mood to shift and build. I think of the scene where we meet Bryan Tyree Henry’s character, freshly released from his own wrongful incarceration months before Fonny will have to face a similar injustice. He and Fonny are affably chatting about life and art (Fonny is a talented woodworker) when Fonny finally broaches the subject of prison. His friend’s face falls and his voice drops to a choked whisper. Have you ever spoken with someone who has been through trauma, or gone through something traumatic yourself? There’s a feeling when you’re laughing and talking about trivial matters (music, sports, movies) and the conversation suddenly turns to something painful or tragic. And a tidal shift in mood seems to completely envelop the room. When Fonny and his friend suddenly find themselves discussion racism and trauma and being locked up, the air becomes palpably heavy. Barry Jenkins conjures that feeling through some uncanny combination of lighting, his brilliant performers, and the subtle camera movements between them. It’s hard to sum up what he does with tone in this film. The best I can do is to say that he has an almost impossibly sharp sense of what is going on between his characters, in ways that are both spoken and unspoken. It is as if Jenkins is an unseen character himself, acting alongside his cast. He also has the aid of the best film score of 2018 and of at least the last few years. It is a luscious, undulating fog of beauty, pain, and nostalgic reverie. In a film of uncommon technical accomplishment, composer Nicholas Britell deserves particular commendation. Like the film it complements so beautifully, it is tender, romantic, disorienting, painful, and transporting. It is just one more way that If Beale Street Could Talk manages to channel adversity and wrenching heartache while rising transcendently above them.