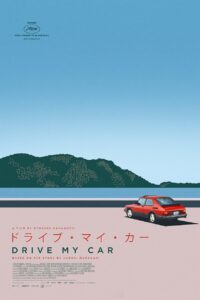

If there’s been a message I’ve picked up over the last couple years, it’s been that movies are a life raft in rough seas and that movies are utterly powerless to intercede in concrete matters. In Woody Allen’s masterpiece The Purple Rose of Cairo, Mia Farrow’s character learns that cinema can make a drab life worth living and that art (and, fittingly for a Woody Allen, artists) will not hesitate to let you down. That art can be an emotional balm but that there are limits to its power. If there’s a frustration in treacly love letter to the movies like Empire of Light, The Majestic, and even the very popular Cinema Paradiso, it’s that they do not really see the power of art as being complicated or compromised. Part of paying tribute to the power of art, I think, lies in recognizing the ways it can frustrate us and fall short. 2022’s The Fabelmans (a surefire entry on next year’s list) does well to find the nuance in its assessment of movie-making and how it can bring psychic turmoil as well as joy and relief. Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s staggering 2021 gem Drive My Car, has a similarly complicated view of art, namely of the theatre. As its devastated play director marks the second anniversary of his wife’s very untimely death, there’s no sense that the play he is directing will be the thing to help him salvage something out of the tragedy. To paraphrase a lyric from acclaimed alternative band Superchunk, art cannot bring people back to this Earth. Producing a successful play cannot undo this man’s heartbreak. Putting on a show does not hold some miraculous power to banish sorrow and pen a new, happier chapter in his life. And it certainly does not hold any easy answers to his loss and how to cope with it. And yet, the three perfect hours of Drive My Car are marvelously healing in the end. Art does not really save the day in the film and one could argue that the directing of the play adds some strife and stress of its own, as the artistic process can often do. Maybe it’s just simply that grief gets shaped and sanded down by time and creating art is something one can do to fill that time. Art, like so much of what is good in life, cannot erase greif. What it can do is distract us and take our minds elsewhere for intermittent moments. As a character says in “Uncle Vanya”, the classic Chekov play our protagonist is directing, we must endure our share of sorrows and live our lives with the hope that we might one day look back on old pain with something like tenderness. We trudge on to a place where trauma does not go away, but simply hurts less. When I saw Hamaguchi’s film back in early 2022, the film’s notion of wrestling with anguish in a tender, almost optimistic way resonated with me a great deal. 2021 had not been easy, and even the return to my beloved movie palace could only do so much to counter that fact. And now at the end of a blistering 2022, with loved ones lost and new ordeals accumulated, the film’s gently walloping power has grown exponentially.