In the very beginning of The Lighthouse, there is only sound. The roar of the choppy Atlantic Ocean and the hoarse scream of the wind. Then, the black screen gives way to its first black and white image, but damned if you can tell what you’re even looking at. We are peering out across a dim and very foggy expanse of chilly water, but it takes quite a few seconds before we can make out the image of a large steam freighter laboring its way toward us through the angry surf. It feels important and apropos that we hear Robert Egger’s stark, briny and thoroughly unhinged film (his sophomore follow-up to 2015’s brilliant The Witch) before we see a solitary frame of it. That sense of confusion, the uncertainty of what this film even is, kicks in immediately and does not relent, even as discernible images and the semblance of an explicable plot gradually come into focus. Long after my eyes had adapted to the film, my brain was still squinting and straining to make sense of it all. Behold 2019’s foggiest motion picture, in more ways than one. Abandon all hope, ye with a need for cinematic stability; for a working internal compass and a clear sense of where a picture is taking you. As someone who greatly prizes niceties like thematic focus and cohesion, The Lighthouse scoffed and brayed at my pretty, landlubbing notions of what a film could and should be. On a third viewing, I still emerged deliriously incapable of really explaining it to anyone. On my first viewing, I couldn’t even begin to break it down for myself. All I knew is that it was gorgeous, formidable, disquieting, raucous, hysterical and insane. In short, I knew that I loved it.

Now, it’s really not so daunting to give the most basic plot synopsis of Robert Egger’s enigmatic thriller period chamber piece. Taking place over a period of some months in the 1890s, The Lighthouse is the story of two men (this is almost completely a two-hander) hired to spend a single month manning and maintaining a lighthouse on a very remote island somewhere in the desolate, choppy North Atlantic. The younger man, who calls himself Ephraim Winslow, is played by Robert Pattinson, whose brilliant work here shovels another foot of dirt on top of Twilight’s mangy head, after his 2017 double whammy of Good Time and The Lost City of Z. The older man is Thomas Wick, played by Willem Dafoe in a performance that challenges The Florida Project for the finest work of his career, and whose blustery bigness is fathoms removed from Florida’s sweet, understated humility. The rocky island where the men do their work is an unforgiving no man’s land, battered by wind and wave and hectored by relentless seabirds. The lighthouse and the rest of the man-made structures are in varying states of disrepair, including a water cistern too putrid with filth, algae and bird feathers to ever truly be clean again. The living quarters are cramped and creaky, and Dafoe’s grizzled old sea dog is constantly farting. Added to all of this, and making the months together tense and strained, is the fact that the two men are not here as equals. The older man is the younger man’s superior. This means that Ephraim is tasked with all the most dangerous and demeaning tasks, while Thomas gets to play delegator and administrator. Thomas updates the record books, while Ephraim empties buckets full of shit. Thomas gets to oversee and tend to the lighthouse’s lamp (which he jealously covets), while Ephraim nearly breaks his neck whitewashing the tower. Thomas has all the power in this professional relationship, and the way the claustrophobia and their testy master-servant dynamic compound one another makes up a lot of the business of what happens in The Lighthouse. Another major plot point is Ephraim’s repeated run-ins with a belligerent seagull and Thomas’ warnings not to kill the disgruntled thing, lest he bring the ire of the sea gods down on their heads. As Ephraim and Thomas become uneasy frenemies, with the help of countless bottles of rum, the one fact comforting them is that the job will end in a mercifully short four weeks. It hardly even seems a spoiler to say that circumstances conspire to extend their stay this barren rock for a good deal longer than that. Among the myriad things it is throughout its runtime, I suppose The Lighthouse is technically a survival film, with two men trying to stretch their provisions and their cases of rum long enough to get out of their craggy purgatory and be blessedly freed from the hell of each other. But I have never before thought of it as a survival film because what it really is is a demented, howling deep dive into the psyches of its characters and the see-sawing codependency of their love-hate relationship. Let me put it another way. Now that I have described The Lighthouse’s plot in basic, comprehensive terms, disregard all of that. This film spits grain alcohol in the face of basic terms. It dashes comprehension upon the rocks.

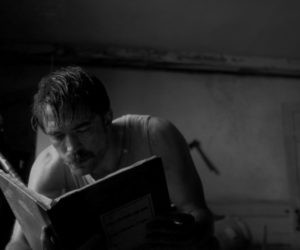

And speaking of on the rocks, The Lighthouse is unquestionably the year’s most inebriated (and inebriating) film. Stranded in the middle of a frigid, inhospitable sea, there is precious little for our unfortunate characters to do but work and get blind drunk. Robert Pattinson’s character starts the film refusing to so much as toast with his superior because the lighthouse regulations forbid it. Steadily though, the arduous labor and the isolation gnaw away at his resolve to stay sober, just as surely as they eat away at his sanity. And young cinematographer Jarin Blaschke (whose eight feature film credits include his stellar work lensing Eggers’ The Witch) camera follows suit, moving from pristine static shots in the early going to compositions that heave and list like a ship in a squall. The camera races, lurches, and tilts like an unhinged drunkard and the dialogue (full of beautifully arcane nautical-speak to start) becomes increasingly, almost absurdly operatic. That is, when the dialogue isn’t pure slurring gibberish, as when Ephraim’s tongue tries to recite a sea shanty that his rum-addled brain cannot possibly recall the words to. The Lighthouse joins films like The Shining and Black Swan in making the steady erosion of communication and reason feel viscerally thrilling. Films like these depict descents into madness in ways that are kinetic and wholly unbound from sense. And there is no separating the film’s jittery perspective from the escalating paranoia and lunacy of its two protagonists. The Lighthouse does not set out to document and understand madness from a remove, but rather to go mad itself and have a seasick blast doing it. The Lighthouse spends the better part of its runtime having the kind of bender that makes you wish yourself dead in the morning. What has maybe gone unsaid thus far is that, for all its moody lighting and ominous atmosphere, The Lighthouse is an utterly engaging experience in its bizarre way. For a thorny, challenging art film, one whose meaning (and much of its verbiage) can be as incomprehensible as its grog-sloshed characters, this is a highly watchable piece of work. A haunting, delirious extravaganza. Perhaps, as someone says in Lawrence of Arabia, I have a funny sense of fun, but so help me, The Ligthhouse is a whole lot of sinister fun! If you’re at all worried about getting it, my advice is not to get it at all. Let yourself be stupefied and bewildered by it. Let its woozy, blustering, bow-legged dementia take you like a riptide and enjoy its blackout pleasures for their own sake. It’s a film to quake at, laugh at, and get downright blitzed on.

That’s not to say that The Ligthhouse is nothing but pure senseless spectacle. At the risk of getting it all wrong, I’ll proffer a theory on what I think the film is up to. As he did with The Witch, I think Robert Eggers is fascinated by American folklore and tall tales, and what those stories reveal about our national legacy and identity. In The Witch, he played with the old 1600s colonial concept of witches and the thickety foreboding of the Pennsylvania woods to explore how the nation has always been steeped in religious hypocrisy and the fear that undergirds it. He saw how the idea of witches is rooted in our puritanical roots and our insecurities about open sexuality and independent thinking. The Lighthouse opens up the oceanic chapter of our mythology. The Lighthouse is Robert Eggers running a whole host of sea-faring lore (screeching mermaids, phantom ships, krakens, sea shanties, and sea curses) through a phantasmagorical, black-and-white kaleidoscope. The Lighthouse is probably a less pointed film than The Witch, in that it does not appear to have a singular social ill in its crosshairs. Maybe the point isn’t really to get The Lighthouse in any clean-cut way, but simply to acknowledge that the enigma of America’ soul, or at least fragments thereof, lie in its folk tales and legends. Paul Bunyan as the benevolent take on our taming of the wilderness. Pecos Bill lassoing tornados and making the West habitable. The Lighthouse is a collage of nautical myths (with a sprinkling of the Greek legends, Prometheus and Poseidon). It is particularly interested in the myths where tiny human beings try to vainly assert themselves in the face of massive, all-powerful forces, be they the gods or nature itself. Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s epic poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, whose narrative The Lighthouse very obviously borrows, is the tale o f a man punished for killing a seabird and daring to think himself superior to the laws of nature; to the codes and superstitions that all sailors are commanded to follow. Unpacking this film’s connection to Ancient Mariner alone could take pages (before we get to Prometheus and sea monsters and every other reference found in this most allusive of films), but I think it’s enough to say that Robert Eggers is exploring the value and the psychic weight of narrative. How it helps us define ourselves and how it also shackles us to the boulder of tradition. These stories we tell ourselves are so very revealing and so very burdensome.

How terrific and fitting then that, in telling this tale about trying to vainly skirt old myths and superstitions, Robert Eggers has made something so radical and unique. He has made his own glorious middle finger to the film gods. One of the joys of Cinema 2019 has been the nimble defiance of categorization, from Greta Gerwig’s gleeful feminist tweaking of Little Women’s ending to Parasite’s balletic genre shape-shifting. Marielle Heller gave us a Mister Rogers movie that, in its own words, wasn’t really about Mister Rogers. If the theme of The Lighthouse is humanity wrestling with whether to obey old rules or burn the rulebook, The Lighthouse leads by rebellious example. The film has been marketed as an arthouse thriller, which makes sense given its ominous sound design, foreboding setting, and shadowy camera work. Of all the things it is, The Lighthouse is most apparently an atmospherically moody thriller. But it is also a wickedly black odd couple comedy about two mismatched roommates and the tug-of-war of their distaste and strange bedfellow affection for one another. It is also the year’s weirdest, most singularly audacious workplace comedy; a classic story of a man having to do the dirtiest, smelliest, and most thankless parts of the job, while his boss sits cozily in the corner office (in this line of work, the corner office comes with the best view and giant revolving light). I cannot stress enough how genuinely funny The Lighthouse is in its menacing, unnerving fashion. This is due in large part to two phenomenal actors, drunkenly boasting and jigging and bouncing off of each other. It is a ghost story that draws humor from its own feverish pitch; by playing its intensity with such unashamed fervor that it cannot help but also be a hoot. In that way, The Lighthouse comes to feel like a sea shanty in cinema form; strange, meandering, loud, and darkly ridiculous. Thank the film gods for something this bold, mysterious and strange.

There’s no easy answer to the question, “What is The Lighthouse?”. It’s a maddening, giddy little mirage; a sinister and lively siren song. It’s probably folly to try to pin it down and explain it, though it’s also a lot of fun to try (again with my funny sense of fun). Maybe the best thing to say about it is that it’s something new. It’s a reminder that we can still have new and startling and original creations, more than a century into this medium. It’s a thing entranced by mythology and history (the dialogue has been meticulously researched from old nautical logbooks) and driven forward by its own wild imagination. A film that juggles literary allusions and fart jokes. A film where a go-for-broke Robert Pattinson confesses to having romantic urges for mermaids and filet mignons. A film that punctuates a long, impassioned Willem Dafoe soliloquy about vengeful Poseidon with 2019’s most perfectly dry punchline. It’s a nautical buddy comedy, a spooky sailor’s yarn, and a maritime cultural encyclopedia all mixed together in a dirty, dark glass. It’ll make you uncomfortable. It’ll make you giggle. It’ll probably make you lose your mind. Don’t even ask what’s in the thing. Down the hatch.