I don’t entirely know what changed between 2017, the year of Martin McDonagh’s Oscar-courting Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri and 2022, the year of his perfect black dramedy, The Banshees of Inisherin. I can say that America’s leadership turned over, even if a lot of the rancor of the Trump years barely feels like it’s abated. Three Billboards, a film about forgiveness and redemption, specifically set within red state America, debuted into a culture that was vociferously and publicly trying to exorcise its racist demons. As many of us were calling out the hypocrisy of patiently abiding bigotry, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri wandered into the fray and posited a facile question: what if a violent, ignorant racist were also a good person just trying their best (Jojo Rabbit would pose the same question about Nazis a year later)? I still find McDonagh’s 2017 film fundamentally wrong-headed, the cinematic cousin to the myriad New York Times op-eds about the wholesome, domestic lives of white supremacists. Useless and obtuse at best; insidiously accommodating to hatred at worst. The major reason The Banshees of Inisherin works so beautifully where Billboards faltered is not just the new-but-not-that-new political moment it arrived in but its decision to not try to speak directly to the moment. And, in such a way, to speak inestimably more eloquently to the moment (its isolation and loneliness, its acrimony, the sputtering struggle to connect with one another) than Three Billboards’ America-targeting hot takes ever could. It is a film that hits more pointedly for aiming at a larger target. The setting this time is McDonagh’s own native Ireland. And, while I can only speculate whether the more familiar environs has helped to ground him, the results are hard to argue with. He has made the most emotionally grounded, eloquent film of his career. And, McDonagh enthusiasts will be pleased to note, he has grounded himself without losing so much as a dram of the puckish, fanciful, anarchic liquor that runs through his veins. He is still the same clever imp making dark, uncomfortable jokes and holding very little sacred. But that impishness has a glorious soulfulnesss here that surpasses even the most poignant moments of his feature debut and former high watermark, In Bruges. Both artistically and geographically, cinema’s hyperliterate enfant terible feels more at home than ever.

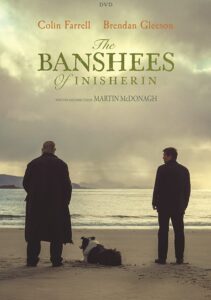

Home is McDonagh’s green Ireland, though a somewhat fictionalized version. The remote island of Inisherin is a made-up place, barely touched by the realities of the film’s 1920s setting. The Irish Civil War is grinding to a close on the mainland and only exists to our isolated characters in the odd far-off gunshot or in rumors told by the contemptible local constable. In this verdant backwater lives an endearing dimwit named Padraic (an astonishingly funny and moving Colin Farrell) and his older friend, a surly, frustrated intellectual named Colm (the great Brendan Gleeson, who handles this scintillatingly sharp dialogue so well that some have given him the backhanded compliment of being “effortless”). On a day exactly like every other day in these beautiful boondocks, Padraic walks the old country road from his tiny farmhouse down to Colm’s seaside cottage to pursue their daily tradition: an early afternoon round at the village pub. When he raps on his friend’s window, he sees Colm inside stoically staring at the wall and not responding. Puzzled by Colm’s silence, Padraic walks up to the bar alone and the barkeeps are surprised to see him without his usual company. They wonder if the two chums might be having a fight and Padraic’s sharp-tongued spinster sister Siobhan (a revelatory Kerry Condon) wonders the same. When Colm finally turns up at the pub (alone but for his dog), Padraic gives him a blanket apology for whatever he’s done to wrong his friend. But Colm tells him there’s nothing to forgive. “I just don’t like you anymore, ” Colm flatly explains. “But you liked me yesterday,” Padraic stammers back in dismay. Colm has become keenly aware of the passing years and feels he has little to show for his time on this desolate corner of the planet. He wants to think and write music to leave to the future generations, but his scant time is being rapidly siphoned away by the banal rituals and mundane conversations he shares with his dull friend, who he bluntly calls “a limited man”. Colm simply does not want to associate with Padraic anymore, and he is unmoved by the reminders from Siobhan and the local priest that cutting a friend off just for being a little boring isn’t very nice. Padraic doesn’t take this rejection well and their ensuing fallout takes a McDonagh-worthy turn for the blackly comic when Colm backs up his antisocial request with a grisly ultimatum. Every time Padraic ignores his wish for silence and solitude, Colm will cut off a finger; from his fiddle-playing hand first. McDonagh’s film is a vicious and bleakly lyrical parable about social niceties, civil obligations and estrangement that drags the mores of an entire Irish town down into a peat bog.

As a child of largely Irish ancestry, my first exposure to my ancestral land came through media that depicted the Irish as kind of amiably prone to squabbling. McDonagh’s is certainly not the first film to depict two Irish men bickering. It’s a romantic cliche that endures in films like The Quiet Man and Darby O’Gill and the Little People. The Irish are portrayed as rowdy, drink-loving fighters. Insults and barbs are their love language (and their hate language). Bar fights and fisticuffs are seen as almost whimsical and at the very least spirited. That cliche can be fun, but McDonagh is here to take the ever-fecking piss out of Hollywood-friendly Irish whimsy. His film starts not unlike Kenneth Branagh’s milquetoast Irish autobiography, Belfast, with shots worthy of an Irish tourism commercial. Lush green pastures, narrow lanes choked with sheep, rugged coasts and bracing sea foam. By design, he is situating us in the Ireland of Tinseltown’s reductive dreams. He is placing us in the same charmingly folksy Ireland of films like Waking Ned Devine, only so he can torch it all by the end. He knows audiences will coo at the quaint greenery and colorful locals and he hopes they do. It just makes it all the funnier by the film’s finale, when Martin McDonagh informs us with a wry chuckle that this little emerald paradise may as well be Hell on Earth. The painterly vistas and rolling hills are the kind of scenery that prepares us for romance, wit and wonder (the wit is here in droves), but McDonagh delights in having those landscapes play host to a tale of wounded pride and wicked human pettiness. Of all the jokes in this riotously funny tragicomedy, its charming, rural mise en scene may well be the funniest of them all. Idealize the Emerald Isle all you want as far as McDonagh is concerned. And sure, it does look nice. But there is no place in the world too awe-inspiring or magically picturesque to be sullied by the very basest and most childishly stunted of human behavior. And there’s something in that universally mean notion that is oddly kind of beautiful.

McDonagh gets a lot of mileage out of his quaint, pastoral setting. One of the chief criticisms of Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri was that McDonagh was training his sardonic crosshairs on rural America when he had never set so much as a foot there. His barbs lacked specificity and accuracy because he only had the most generalized idea of the place he was sending up. Coming home to his native Ireland seems to have focused him and rejuvenated his peculiar knack for marrying the poignant to the mercilessly cutting. He also mines the Irish Civil War backdrop well without making too much out of it. Quite to the contrary, these characters are so isolated and cut off (from Ireland and from each other) that the Irish Civil War hardly exists to them in any real sense. It’s as much an abstract idea to them as it is to McDonagh’s screenplay. The Civil War exists for McDonagh as metaphor and as a larger story playing out in tandem with the film’s very small story. All shapes and sizes. The War is the epic macro version of Banshees’ microscopic feud, and McDonagh is suggesting a world full of meanness, stubborn pride and childish squabbling. Siobhan begs her brother to leave Inisherin’s lonely gloom, but it is not simply this desolate place that traps Padraic and his fellow villagers. It is the human condition and everything small and self-defeating inside of us. What I love about McDonagh’s laceratingly funny parable is that, while the Irish setting is important and personal to the writer-director, Banshees of Inisherin is a story that could be set anywhere and at any time in human history. It could have been the tale of two ancient Greeks or two lords in Orwellian England or two hunter gatherers on the Serengeti in the 1800s. It could be one year ago or one thousand In the distant, dystopian future or at the dawn of mankind. Feuding and pouting and shutting people out are subjects for any era. Falling out with a friend is forever.

More than anything, after growing a little weary of McDonagh’s bratty stylings after 2017, I am over the moon to be a full-fledged fan again. I think there’s something in this breed of precociously hyper-literate writer-director that can slip easily into lazy, self-satisfied territory. Aaron Sorkin spends half his time being one of the sharpest, funniest writers of his generation and the other half being exasperatingly pleased with his own, ahem, liberal talents. David Mamet started out with one of the best ears for insightful, rhythmic dialogue imaginable and a rapier wit for skewering masculinity, but later devolved into a tiresome conservative Zionist. Even Quentin Tarantino, a writer who has been a passionate cinema advocate and hardly ever written anything less than great, occasionally becomes over-exposed and lapses into self-parody. We like our artists to be humble and sensitive but writers like Martin McDonagh thrive on provocation and snark and dynamic writerly flourishes. A fair bit of brazen braggadocio is just part of the sauce for guys like that. Screenplays with that kind of kinetic, show-off style can be thrilling but they can also tip into being smug, self-consciously overcooked and grating. AS much as provocateurs like to pride themselves on pushing people’s buttons, there is an actual artistry to good provocation. You can’t just ruffle feathers and automatically label their discomfort as your success. Banshees of Inisherin is a roaring success because it attacks social norms in a way that doesn’t feel superior to its characters or its audience. This is classic firebrand Martin McDonagh operating with real empathy. It’s a film about human frailty that does actually like people. Nobody is being looked down upon, not even the local creep Dominic (an astonishing Barry Keoghan). Banshees does drag humanity through the muck, but if you look right behind you, you’ll see Martin McDonagh is there, just as caked in filth as the rest of us.

Banshees of Inisherin represents a huge step forward for just about everyone involved. The only exception is the towering Brendan Gleeson, an actor so consistently brilliant that I have heard some accuse his performance of being effortless. My only response to that is that highwire Martin McDonagh dialogue doesn’t get to feel effortless unless the actor speaking it has an impeccable grasp of the material. THere is very little that Gleeson can’t make look easy. Everyone else in the film is raising their career zeniths. Martin McDonagh, usually thought of as a writer first and a director second, creates a gorgeously subtle tone and even creates some rich and memorable shots. Kerry Condon is a sweet, sardonic delight. My only exposure to her before this was Better Call Saul, a great show that gave her its most thankless and uninteresting role. Her performance as Siobhan is so soulful, sad and sharply funny that it should immediately establish her as a star. She should never have to play a blandly supportive girlfriend or daughter-in-law again. Barry Keoghan gives not only his best performance, but one that acts like a proof of concept for the whole singularly strange Barry Keoghan Experience. His Dominic walks a tightrope of characterization. He balances notes of daffy humor, creepiness, pitiable weirdness and sweetness in such a way that the character shapeshifts before our very eyes. McDonagh loves to peel back the layers of his characters so that we check our initial impressions of them, and Dominic may be his best character rug pull yet. And finally, it is such a pleasure to watch Colin Farrell bloom into his full masterful potential. Farrell broke through in the early Aughts in films like Minority Report, but he spent the next decade being repeatedly mishandled by studios who could only conceive of him as the latest leading heartthrob. He was in danger of turning into Ireland’s Val Kilmer: an endlessly gifted character actor doomed to mediocre parts by his own handsomeness. It was Martin McDonagh who finally unlocked Farrell’s true depth with In Bruges. His knack for quick comedic banter and underselling a dark joke. His wonderfully dopey soulfulness. In Bruges showed Hollywood that it had been using Farrell all wrong, that he was so much more than UK-exported beefcake. Banshees of Inisherin soars because it seamlessly blends the wildly funny and the deeply sad. In other words, it’s what a Colin Farrell film should have been all along.