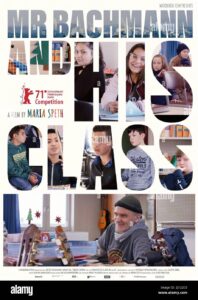

Maria Speths’ patient, gently entrancing documentary, Herr Bachmann and His Class, is a good three hours-plus in runtime (three hours and thirty-seven minutes to be exact), making it the longest film in my year-end list by a solid half an hour. 2022’s best documentary (with no lack of competition) is not just a solid three hours but a good three hours. A lot of discourse over the past year was the old chestnut about movies being longer than they needed to be. It’s a line of argument that gets every bit as tedious as its proponents claim two-plus hours movies to be. On the plus side, it’s an occasion to refer back to Roger Ebert’s evergreen wisdom that no good movie is long enough and no bad one is short enough. While I love watching a short masterpiece like Petite Maman or The Station Agent, some movies thrive on their great lengths. A short Lawrence of Arabia or Boyhood are absurd to contemplate. Simply put, there are very special depths of scale and emotion that can only come from sitting and marinating at length in a film’s ambience; from sitting with its characters for so long that they start to feel like close friends. The crux of the film length critiques is that a great many films don’t put their runtimes to that kind of use, and I agree with that criticism in a lot of ways. Still, as Oppenheimer demonstrated just this summer, there is nothing quite like going on a three-hour journey that justifies and utilizes every minute. That’s a special kind of elation, Now of all the subjects to justify an epic runtime, a year in the classroom of an endearingly prickly German middle-school teacher might not be the first to come to your mind. It didn’t occur to me either, until that three-hour school year neared its end and I found I had become powerfully invested in and attached to this retiring educator and his striving pupils. Three hour films are great for taking us into expansive fantasy worlds with sprawling stories. But Speth’s documentary reminds us that three hours can also be used to take the smallest of worlds and tunnel into them, making them feel deeper, richer and more human than we thought possible.

In my review last year for the stirring rescue documentary, The Cave, I wrote about how, after the apathy and weaponized incompetence of the Trump years, there was something profoundly comforting about watching someone or some group of people tackle a job with intelligence, humility and care. In a year full of visionary cinema, Herr Bachmann and His Class is 2022’s least complicated masterwork. While it has ideas to unpack, it is mostly the simple story of some students (many of them children of Turkish and Middle Eastern immigrants) in a small German city and the softly iconoclastic, very dedicated man who spends the last year of his career teaching them. It would be impossible (and tedious) to list off everything that transpires over the course of that school year, but the vibrant quilt of Speth’s wonderful documentary makes one thing pretty clear: Herr Bachmann is really, really good at being a teacher. I don’t have any qualms about spoiling that revelation because Herr Bachmann isn’t a film about what happens in this classroom. To invoke the great Ebert one more time, this great film is about how its events happen. Along the way, we learn of the town of Stadtallendorf’s history, starting as a rural dot on Germany’s map before being built up to serve as an industrial hub in World War II. There’s both an unease and a richness to how this place, once designed to aid the Nazi war machine, now provides jobs to people the Reich would have denigrated and dehumanized. Instead, Stadtallendorf now serves as a loving, closely knit community for immigrant children to grow in, though the obstacles to non-white success stil exist in subtler ways. As I noted, the emotional engine of the film is how close we become to Herr Bachmann’s students, how much time we are given just to share in their company. In a film that is about the beauty of education, Speth cruciall never comes close to giving the kids short shrift. Far from it, the attention and empathetic gaze Herr Bachmann and His Class pays to its young subjects is enough to make a great many worthy documentaries feel surface level by comparison. Like the great teacher she focuses on, Maria Speth respects the intelligence of her audience and values ever minute of her too-short time with them.

So much of what makes each cinema year so fun to dive into is the swirl of complex themes and ideas, but i also love Herr Bachmann and His Class for its crystal clear simplicity. There are no intellectual hurdles to enjoying the warmth and compassion in Speth’s film. Here is a documentary that is first and foremost an ode to educators and the artistry of teaching. Whatever personal journey you may have watching the film, what lifts it and moves it lightly along is a straightforward devotional quality. Talking heads are virtually non-existent and Speth doesn’t stop her film cold to wax intellectual on education policy or immigration or any other matter Herr Bachmann happens to touch upon. The best way she knows to pay homage to the world’s teachers is to watch one of them closely and lovingly as he practices his craft. Herr Bachmann and His Class is less an examination of education than a sweet and poetic tribute to education as an idea. To watch this funny, gruffly doting rebel of a man work miracles and form bonds is to think fondly about educators like him, all around the world. To watch this gifted teacher’s very specific methods for reaching his students is to remember that teaching is more art than science (even, I assume, when teaching science). The 65-year old Bachmann, once a less than model student in his own school days, is barely concerned with grades except in terms of what options those grades give his adolescent brood. What he focuses on more is self-esteem, communication, and a spirit of communal support. He rarely raises his voice unless he feels a student isn’t being respected or heard by their peers. He places more stock in questions than answers because questions are the best means to open his students up to each other and to their inner voices. His questions for them are not merely academic and rote, but often are probing and philosophical. He stops lessons to have them play music together. In a marvelous scene, he uses a song about two male lovers to make them confront their feelings and prejudices about queer people. His goal is not to purge their biases, but to bring them into the light. When a young lady finally reveals her discomfort over a man loving a man, he gently asks her where these strong views come from. She waits several beats and bashfully murmurs, “I don’t know.” Bachmann smiles and says, “That’s better.” Not knowing may not be the end goal of education, but Herr Bachmann and His Class keenly grasps how it can be a fine and healthy place to build something new.

This is anything but a bold connection to draw, but Herr Bachmann does give me the chance to praise one of the 2000s more undersung masterpieces. Speth’s documentary reminds me of 2008’s French feature, The Class. Not a documentary but based on its writer-star’s own experiences as a teach in the Parisian public school system, that film was also a deeply immersive and observant odyssey through a single year in the life of a classroom. And like that film, Herr Bachmann and His Class is sharply focused on the aims and cultural biases that run through education systems; who these curricula are tailored toward and who they can blindly disadvantage. Much of the emotional through line of Speth’s documentary is how a large portion of Bachmann’s class are immigrants from places like Turkey, Morocco and the Balkan states, recent strangers to a strange land. A classroom as microcosm for a country’s ethnic harmonies and tensions may seem like an easy metaphor, but under the film’s gloriously natural editing, it is also an eloquent one. The small city of Stadtallendorf was built up and enriched by exploited Turks and Eurasians, people the Nazis openly considered beneath them. This place is not just a home to these immigrants, but a legacy both proud and painful. It is a testament to the lives those students’ parents and grandparents toiled to carve out and an uneasy of the kind of nationalism and racism that still otherizes them to this day. Herr Bachmann is leery of the value of grades, which unsurprisingly favor the natural-born German speakers in his class. The aging rebel has overflowing love for all his class but his heart beams for those barely making it; the ones largely headed for secondary schools rather than the main high school. Many of them spoke effectively no German mere months ago and now they converse excitedly with him. They are not just better at a new language, but have opened up into young adults with a newfound sense that they belong here. That strengthening of dignity and personhood is Bachmann’s true mission, whether the teacher’s manual recognizes it or not. And while Bachmann cannot change the arbitrary systems these immigrant children must navigate, he strives to let them know he sees the true measure of their success. If the man had his druthers, the classroom he loves would go past just being a metaphor for empathy, cultural acceptance and solidarity across national and ethnic boundaries. Those principles would be its true raison d’etre.

Herr Bachmann and His Class is a salute to doing your job with love and intelligence. If there is one identifiable stroke of genius to Bachmann’s teaching style, it’s that he makes everything personal. He has memoires and anecdotes of all his students that he can share with them. He compliments the way one laughs. He talks with them one on one, not just after school but in the middle of classes. In private conversations and soft-spoken, encouraging asides; in warm facial expressions. He knows their families and their home lives. The German school system appears to have just as much arbitrary red tape as any other country’s, but Herr Bachmann’s approach to teaching is anything but bureaucratic. These winning three-and-a-half hours are a balm against institutional coldness, a reminder of the value of treating the young as human beings. Bachmann understands how this personalized touch improves their education, and he also knows how too much of the world treats these kids as faceless cogs and ostracizes them for their skin colors and native languages. Cruel racists first brought their ancestors here to grease the wheels of a totalitarian regime and stay out of sight. They belonged in the factories but never in Germany, and too little of that attitude has changed. Bachmann sees how hard his students have to struggle just to keep up and he lets them know he sees what they are up against. When one poor girl can barely keep her tired eyes open, he lets her go nap on his couch. Bachmann is treating them as human beings, and there is something about in that not just personal but defiantly political. He teaches with an iconoclastic spirit because he understands that showing kindness and respect to immigrants and people of color is sadly a political act in modern society. Bachmann tells a fellow teacher that he once thought about quitting this profession decades ago because he couldn’t figure out how to be himself within the system. He couldn’t square it with his rebellious individualism. Now, with retirement days in front of him, we are watching the last hurrah of a man who figured out how to thrive in this system and win. A man who now works to teach his students the same rebel spirit that saw him through when his self-doubt was deafening. He teaches them how to make their way through an unforgiving society with spirits intact. Learnt he rules, be kind to one another, make yourself at home here no matter what the bigots and bastards say, and fill your heart with the things that really matter.

There’s a concept in documentary film-making called walking with the subject. The crux is that the person doing the studying cannot help but become a part of the study, so they should just become a part of their own work. Join the subject and walk alongside them, instead of trying to pretend like you aren’t there. Charlie Kaufman would approve. Herr Bachmann does not teach from a pulpit but from the ground. He is surrounded by his class and he is an integral participant in his class. He shares his own stories, his passions and regrets, because he is inherently one of them. That seems to fundamentally inform his teaching methods. To truly help people, we must erase the distance between them and ourselves and truly become one with who we are helping. It’s maybe a radical idea in teaching. I’ve had teachers in my family and I’m close friends with teachers and I know there’s a line of thought that says to maintain a boundary of self; to not exhaust your emotional stamina. I don’t know where the truth is when it comes to not getting too involved as an educator, but Herr Bachmann and His Class shows that you can give yourself as a teacher without losing your heart or becoming jaded. And that’s a nice feeling a nice feeling to take away from one 2022’s most deeply felt pieces of work. Speth’s patience and her faith in how compelling this classroom is pays off beautifully. Each of its 217 minutes feels entirely earned. Frankly, I could have watched a miniseries of this school, but I guess good things have to end eventually. We leave the film on a bittersweet note, just as the students do. Sad to say goodbye but hearts full with the people we have met and the lessons we have learned. One student looks at the now-empty classroom and marvels at all the “good things” that were done there. A long runtime is like a classroom. It’s all about what you do with the space.