If there’s been a message I’ve picked up over the last couple years, it’s been that movies are a life raft in rough seas and that movies are utterly powerless to intercede in concrete matters. In Woody Allen’s masterpiece The Purple Rose of Cairo, Mia Farrow’s character learns that cinema can make a drab life worth living and that art (and, fittingly for a Woody Allen, artists) will not hesitate to let you down. That art can be an emotional balm but that there are limits to its power. If there’s a frustration in treacly love letter to the movies like Empire of Light, The Majestic, and even the very popular Cinema Paradiso, it’s that they do not really see the power of art as being complicated or compromised. Part of paying tribute to the power of art, I think, lies in recognizing the ways it can frustrate us and fall short. 2022’s The Fabelmans (a surefire entry on next year’s list) does well to find the nuance in its assessment of movie-making and how it can bring psychic turmoil as well as joy and relief. Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s staggering 2021 gem Drive My Car, has a similarly complicated view of art, namely of the theatre. As its devastated play director marks the second anniversary of his wife’s very untimely death, there’s no sense that the play he is directing will be the thing to help him salvage something out of the tragedy. To paraphrase a lyric from acclaimed alternative band Superchunk, art cannot bring people back to this Earth. Producing a successful play cannot undo this man’s heartbreak. Putting on a show does not hold some miraculous power to banish sorrow and pen a new, happier chapter in his life. And it certainly does not hold any easy answers to his loss and how to cope with it. And yet, the three perfect hours of Drive My Car are marvelously healing in the end. Art does not really save the day in the film and one could argue that the directing of the play adds some strife and stress of its own, as the artistic process can often do. Maybe it’s just simply that grief gets shaped and sanded down by time and creating art is something one can do to fill that time. Art, like so much of what is good in life, cannot erase greif. What it can do is distract us and take our minds elsewhere for intermittent moments. As a character says in “Uncle Vanya”, the classic Chekov play our protagonist is directing, we must endure our share of sorrows and live our lives with the hope that we might one day look back on old pain with something like tenderness. We trudge on to a place where trauma does not go away, but simply hurts less. When I saw Hamaguchi’s film back in early 2022, the film’s notion of wrestling with anguish in a tender, almost optimistic way resonated with me a great deal. 2021 had not been easy, and even the return to my beloved movie palace could only do so much to counter that fact. And now at the end of a blistering 2022, with loved ones lost and new ordeals accumulated, the film’s gently walloping power has grown exponentially.

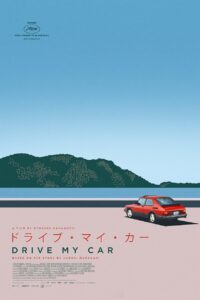

We spend the first thirty of Drive My Car’s poetically observant minutes getting to know Yusuke Kafuku and his wife Oto (Hidetoshi Nishijima and Reika Kirishima, the two most outstanding in a cast full of miraculously sensitive performances), a successful artistic couple in their late forties living in Tokyo. Yusuke is an actor and play director of some renown. Oto is a former actress who has recently found even greater acclaim as a screenwriter for television. They seem comfortably in love though we quickly pick up on a deep undercurrent of sadness between them. We learn that they lost their 4-year old daughter nineteen years ago. They never chose to try for more children but instead have chosen to make do with the blessings of good careers, a nice home and each other. They have pooled their sorrow and their joy together into a life and have done their best to find satisfaction in it. They work, travel and have a respectable sex life. One day, however, Yusuke comes home to a new sorrow. Forced by a flight delay to postpone his trip to a theatre festival (where he has been asked to judge) by a day, he returns home to find Oto in bed with a handsome young star on the rise. Yusuke slips back out the door before anyone can clock his presence and he spends the following weeks or maybe even months sadly holding the secret to his chest. Then one morning, as he heads out to do some work on his latest play (a production of Uncle Vanya that he will direct and star in), Oto brushes his arm and asks if they can talk that evening. Her tone is soft but solemn. He spends hours driving aimlessly around the city in his red 1987 Saab 900 Turbo (a beautifully classy piece of machinery, even to the eyes of non-car guy), absently listening to the tape of play lines Oto has recorded to help him rehearse. Some of the lines even seem to speak to his present fears. When Yusuke finally walks back into their home very late that night, he finds Oto dead of a brain hemorrhage. Whatever words she had to say are now lost with her. The fateful title card appears and lets us know that this whole rich, poignant chapter has just been prologue. The main story, about Yusuke directing an internationally cast production of Uncle Vanya two years after Oto’s death in the city of Hiroshima, finally begins. Most of the characters (save for Oto’s partner in infidelity, Takatsuki) are as new as the changed surroundings. But Yusuke and the red Saab remind us of where it all started; of the tragedy that sits just a short distance back in the rear view mirror.

What plays out over the next two and a half hours in the beautiful, haunted streets, parks and waterways of the city forever tied to memories of atomic devastation is as much about the shadows of the past as it is about the present rehearsals for a classic Russian play. Yusuke Kafuku arrives ready to work again but pretty disengaged from the world of people. He is polite and cordial with the theatre’s literary advisor, a sweetly attentive younger man named Yoon-Su, but he is taken aback when the playhouse informs him of their new automotive policy. Due to a recent unfortunate accident that resulted in a loss of life, the company insists on assigning its directors a chauffeur. It’s just to appease the insurers but it comes as quite the imposition to Yusuke. For one, he’s protective of his stylish little car. He’s also been looking forward to some time spent in privacy between rehearsals and the hotel that he very intentionally picked out on the opposite side of town. And he’s uneasy with having this driver, a quietly professional young woman name Misaki (played with stoic intelligence by Toko Miura), listening to the tapes he uses to go over the play. The tapes narrated by the voice of his recently departed wife. Drive My Car is about the tension between sheltering our private pain and the shock of letting people into those secluded spaces. It is not only about Yusuke’s quiet despair but about ordeals going on around him. There is the backdrop of Hiroshima with its millions of harrowing memories hanging over it like a psychic fog. And his capable new driver, who quickly earns his trust through sheer dutiful unobtrusiveness, has a gutting backstory of her own; a sad hometown and an agonizing past she is trying to gain some distance from. Yusuke has cast the young actor who had slept with his wife in the role of Uncle Vanya. Is this an act of self-flagellation, a reminder of the betrayal that shadowed his last days with Oto? Or is it an attempt, conscious or subconscious, to actually engage with the past and find some kind of resolution? Drive My Car presents a tranquil, poetic rumination on the tug-of-war between pressing on through our pain (the will to keep working, as one character in Uncle Vanya says) and giving up. Yusuke seems perched precariously between the two at times. He works diligently enough on the play, but he also seems intent on sealing it off from the sunlight, from even the faintest trace of levity or hope. He initially insists on flat, dry line readings from his cast. Despondent line readings even, much to the befuddlement of his actors. And then, through the process of working Chekov’s text, the bleached, sunless tone begins to change a bit. He grows fond of his cast (including even the hot-headed horndog who his wife once took to bed). He puts more trust in their instincts. This does not entire dispel the gloom, but time and the pursuit of a project gives Yusuke enough to move forward one day at a time. While Yusuke’s own peace of mind is touch and go, it seems that the play at least will be just fine.

It is not an extremely plotty film, but Drive My Car‘s emotional arcs have a staggering richness to them and it has an understated empathy that quickly endears us to all of its characters. Even those who are, by their very nature, frustrating. Broadly speaking, I think it’s a story about the forces that disorient and bewilder us and the desire to break through that confusion. To want to feel more awake, more engaged, more alert are all desires that help describe what it is to want to be alive. To want to know more of the world around us and the people in it, rather than hiding our pain-addled heads between our knees. It is a film about the warring beauty and heartbreak of loving a person and trying to know them. Beyond the painful loss, it is that nagging fear over how well he knew his wife that makes his grief even harder to put to bed. While giving Takatsuki a ride home, Yusuke has his wound reopened when the young lothario shares a story with him. Once, when Takatsuki and Oto were together (Yusuke knows exactly in what manner they were together even if Takatsuki does not directly say), Oto was shared a story she was writing with him. It’s a story that Yusuke though only he knew, for we learn early in the film that Oto came up with her stories during sex. Yusuke’s palpable, heartbreaking hurt in this scene (Hidetoshi Nishijima is masterful here, as he is throughout the film) is not simply from being reminded of his wife’s infidelity. He is experiencing a new, more lacerating loss of intimacy. He has lost the feeling that this certain story belonged only to Oto and him. In the best scene in all of 2021 cinema, the often vain Takatsuki offers the grieving man a great and unexpected piece of wisdom. He suddenly seems to understand what Yusuke understands; his actorly instincts finally reveal themselves. Takatsuki softly waxes to Yusuke of the impossibility of completely knowing the people we love. There will always be some small unknowable piece of the person across from us. But we can find beauty in that mystery as well as sorrow. “But even if you think you know someone well, even if you love that person deeply, you can’t completely look into that person’s heart. You’ll just feel hurt,” Takatsuki says. “But if you put in enough effort, you should be able to look into your own heart pretty well.” Out attitudes towards the communication barriers we find in each other can be an occasion to feel love even more deeply. We do not have to see the inevitable distances between one another as defeat. We can feel gratitude that a person is willing to let us know even a small part of themselves and that they in turn try to know us better. It is something we see in the film’s other marriage between Yoon-Sun and his wife, who can only speak through Korean Sign Language. Yusuke has dinner with them and is impressed that Yoon-Su was able to learn a new mode of communicating for his love. Yoon-su sweetly replies back, “I wanted to know her language. So I studied it.” Maybe we can never completely bridge the gaps in understanding one another; a spot we can’t look into where something dark swirls, as Yusuke puts it. But there is more profound beauty in the efforts people make to reach one another than there is despair in the unknowable. That effort to know as much as we can about our loved ones is what devotion is. That is what love is.

More than halfway through Drive My Car, as Yusuke and his drive are still trying to heal from their past tragedies, a new tragedy befalls the production and throws the fate of the play into uncertainty. The theatre company gives Yusuke two days to decide if the show will go on or if he would rather end the whole thing. It is enough time for he and Misaki to take a whirlwind trip to her hometown. For her to share something of her own trauma with him. And so, in yet another of 2021’s most breathtaking scenes, they hit the long road. They just drive. They drive single-handedly and for the most part quietly. They enjoy each other’s silence as they hurtle across great distances. Through tunnels in great, piney mountains. Across flat green farms. Onto a ferry that spirits the red Saab over a choppy sea. The spaces are, like the silence, vast and strangely comforting in their quiet impartiality. The space does not offer platitudes or reasons, only itself. Only a canvas for our characters to project their unspoken thoughts and feelings onto as they motor along. Both of them have suffered enough to know that sometimes there’s just nothing to say. This kind of observant stillness is the key to Drive My Car‘s tidal power. It finds volumes in what is unspoken and ineffable. Do our feelings, good and bad, our love and our pain, exist not only in words but in the physical things we touch? In possessions and rooms and cities? Does a long-destroyed house feel the absence of its dead inhabitants? Can a little sports car bear witness to its riders confessions? Do the sidewalks of Hiroshima hold back tears for the ones who vanished in an instant eight decades ago? Why can a long road trip be such a blessed way of resetting ourselves. Is there some psychic power in the spaces we cross, in the road itself? Or, like the album we pop in the disc player, is it just that crossing the space gives us a way to pass the time? And if we hurtle across enough time and space can we find some net positive? Some happiness, closure, comfort or perspective? Whatever the answer, crossing space and time does allow us to follow the advice contained in Uncle Vanya, which is to simply move forward and live. It gives us a way to bear our hardships.

We also bear with it by turning to people. 2021 was our first year lived in the immediate aftermath of COVID. We tentatively left our constricted spaces for more than just a trip to the store and we started to see each other again. Drive My Car feels like the perfect choice to represent a year so confusingly riddled with joy, pain and renewed connection. It is a film about acknowledging grief and finding some strength in being around one another. If nothing else, putting on Uncle Vanya forces Yusuke to do something that requires collaboration and connection. It requires him to act out the role of a an engaged human being, if only for the duration of a day’s rehearsal. There may be no magical healing property to art in Drive My Car, but the play does end up doing everyone some good by the end. You can detect some kind of healing in how the rehearsals progress. Yusuke Karufuku starts his actors off in a sterile room reading lines in dispassionate, glazed monotone. He does not want his show to radiate a warmth that is missing from his own life. He flatly refuses to act in the production because, as he tells Takatsuki, the words of Chekov draw painful truths out of you. He is terrified to subject himself to that, to be that terrifyingly open in his current aggrieved state. But warmth does find its way into all things, however much Yusuke resists it. He quickly becomes extremely fond of the woman he did not want behind the wheel. His hardened feelings change. “I’m glad she was assigned my driver is how I feel now,” he confesses to Yoon-su. He is invited into the home of his assistant and he gets to know him. He softens in how he directs his actors. The man who reminds him of his anguish offers him a comfort he never could have foreseen. Life starts to stir. The rehearsals move outside into the verdant, sunny space of a nearby park and Masaki now watches the rehearsals by Yusuke’s side. She does not feel the need to wait silently in the car. Death and winter are inevitable, but they are not the only inevitabilities. Life returns to full bloom, whether you wish it to or not. Try as you might, you can never hold back spring.