Less than 15 minutes into James Ponsoldt’s beautiful, witty, life-affirming teen drama, the director does something quietly remarkable for a “high school film”. For the first time, the camera really zeroes in on the faces of the two leads and stays there. As Sutter Keely, a boozy, cocksure party animal, shares his first lunch with Aimee Finecky, a kind, bookish and sweetly self-effacing young lady, we drink in every detail of their faces, with just enough of their shoulders in the frame that we can catch the incredibly natural rhythms of their body language. The magician is showing us there are no strings holding up the performances or the film itself. The best magic tricks always make the complex look simple, and what could be more seemingly simple than training your lens on the characters and daring not to pull away? These two young actors are really doing all of this right before our eyes, and we remember that great screen-acting is a high wire act that you can not bring yourself to look away from. The Spectacular Now is a quietly revolutionary high school love story because it fully commits itself to the simple act of observing its relatable, confused, hopeful characters. It refuses to let any of them become familiar archetypes, even though we can clearly see the eraser marks of what they could have become in lesser hands. During that first lunch, Sutter asks Aimee how she sees herself within the social scheme of the high school, and her reply is like a metatextual critique of every lazy, superficial jocks-and-nerds teen drama that ever existed. She smiles and meekly says, “I would like to think there’s more to a person than just one thing.” This could be the mission statement for this entire wise and witty film.

The Spectacular Now opens with Sutter writing a personal essay to a college admissions board and the film uses that narrative framing device to introduce us to the character and his world. Sutter is the epitome of wry, cool confidence, like a younger sibling of Lloyd Dobler if he had Ferris Bueller’s uncanny people skills. He flits easily among social circles. He parties with the beautiful people and dates a popular girl, but he also spends a lot of time with his sweetly awkward best friend. He charms athletes, nerds, teachers, and supervisors alike, with the charisma of a young man who has learned to never sweat. In the opening monologue, Sutter’s girlfriend Cassidy (the wonderfully understated Brie Larson from Short Term 12) has dumped him over a misunderstanding involving another girl in his car. He informs us he was simply trying to help his friend lose his virginity. Everything in this opening – popular parties, relationship snafus, trying to help nerdy friends with their sex lives, essay-based narration – has been featured in countless movies about high school students falling in love. The great thing about The Spectacular Now is that it transcends all of that without losing authenticity. I do not know that I have seen a movie quite like this because movies of this sub-genre so rarely have such love and unwavering compassion for any of their characters. From jocks and bookworms to professors and parents, The Spectacular Now has empathy for every last one of them.

The opening narration lets us know about Sutter’s current relationship issues, but its main function is to allow us to see the subtle shades of his personality. We learn that Sutter has a tinge of youthful invincibility, but that he also cares deeply about the people around him and seems to genuinely enjoy helping others. Unlike many a popular smooth-talker, Sutter’s major failing is not arrogance. His problem is that he really, really loves to drink. At the end of the opening narration, Sutter, reeling from his breakup, drives drunk and jumps out of his car at 20 miles per hour. Woodley’s Aimee Finecky discovers him the next morning, passed out on a neighbor’s lawn. She gives him a ride to his car and he helps her complete her mother’s paper route. They talk with the sweet, fumbling earnestness of two fundamentally decent people who are still figuring out their places in the world. Before parting, they agree to have lunch together next week. The development of their relationship from relaxed friendship to sensitive affection to blushing love is the movie’s central focus, and that turns out to be a great thing. After less than five minutes with these characters, I was ready to blissfully follow them anywhere. That said, it is a wonderful affirmation of our faith in these characters that the script gives them a path full of tenderness, good humor and unfussy emotional depth to stroll along. The writing, a thing of quietly literate beauty, works to deepen the characters without ever trying to upstage them.

Of course, the film has some standard elements of melodrama, involving Sutter’s burgeoning alcoholism and his desire to reconnect with the father who stopped being present years ago. Fortunately, this is where the film’s simple investment in nuanced characters and marvelous performances once again sees it through. When Sutter and Aimee finally make a fateful trip to see Sutter’s estranged father and find out what a boozy shell of a man he truly is, The Spectacular Now could have at last succumbed to feeling pat about addiction. But the heavier tropes of alcoholism and the long shadows of dysfunctional fathers never cheapen the film because the actors simply will not allow it. As Sutter’s father, the terrific and versatile Kyle Chandler subtly and sensitively suggests what Sutter could become if he does not learn to put his relationships first: a man who loves life when everyone has a drink in their hand, but has still not figured out how human beings weather the rest of it. The scenes with Chandler work beautifully because their purpose is not to glibly claim that Sutter will be unable to function in society. God knows, many alcoholics do. Instead, the source of tension is whether the deep self-loathing that compels Sutter to constantly drink will impair his ability to connect with the many people who care about him. At heart, The Spectacular Now is an emotionally charged film about wanting to be alive, present, and appreciative of the people who try to love us.

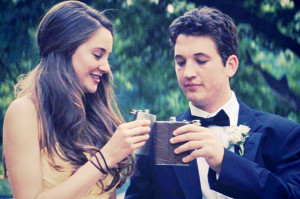

Above all, Ponsoldt’s high school movie is a call for us to view teenagers with complete empathy. Too long have movies about the high school experience viewed teenagers from an adult’s remove. Watching Ponsoldt’s wonderful gem leaves you scratching your head that so few film teenagers feel even remotely fleshed out. Part of it is that performances this generous and attuned only come around so often. The odds of even one young person giving a performance this natural and assured are slim. This movie finds two of them, and that’s before we get to the remarkable shading and steely intelligence that Brie Larson brings to the austere ex-girlfriend archetype. Miles Teller deserved a Best Actor nomination for taking what could have been a standard rogue on a journey of self-improvement and imbuing him with raw humanity and a sense of humor so unforced that his line readings feel improvised. Shailene Woodley completely matches him while finding a rhythm all her own. I was tremendously fond of Woodley’s performance in The Descendants a couple years ago but it also had its detractors. Aimee Finecky should lay all doubts to rest that Shailene Woodley is a major talent. Her Aimee is bookish and shy, but her warmth and gentle way with people give her nuances that categories like “nerd” and “girl-next-door” utterly fail to take into account.

Look at the quiet, heart-felt dignity of the scene in which Sutter and Aimee make love for the first time. The film does not treat sex as a vulgar joke. It does not cut away uncomfortably to a Blink-182 song. It also does not gaze voyeuristically upon Aimee and Sutter. We know they are naked but the camera would much rather stay on their faces, in order to catch every nervous giggle and rapturous smile. It is exhilarating and moving to see a story like this portrayed with such clear-eyed grace and compassion. Ponsoldt proves he has the talent to inject effortless humanity into a tired old genre until it feels lived-in and beautifully raw. If every film could be this emotionally immediate and fervently human, I would gladly stop paying heed to genre classifications altogether. I would much rather believe there is more to a movie than just one thing.