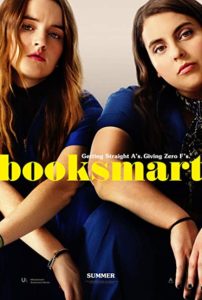

Booksmart, Olivia Wilde’s sprightly, compassionate, and unyieldingly hilarious teenage comedy is all about cutting through our one-dimensional, ossified perceptions of each other to find the messier human depths underneath. In honor of the year’s best (and most surprisingly deep) pure comedy, I’ll start us off. I have done Olivia Wilde a disservice. The first time I ever became familiar with the actress-turned-dynamite-debut-director (not in person, we have not been formally introduced), I was very unfair to her. She was making what would be her big splash in 2010’s well-scored but dramatically inert Tron: Legacy and I was unimpressed by the performance, as I was grumpily unimpressed by just about every non-Daft Punk element of that film (my spouse even made a sketch commemorating my fabled cantankerousness at that screening). As Olivia Wilde quickly reached It Girl status and became a regular fixture in the world’s magazine racks, I shrugged. “The woman who played the algorithm?,” I mumbled to myself. I just couldn’t see it. I was, to put it bluntly, a total dingus to Olivia Wilde. My stance on Wilde would soften a few years later when I saw her give five beautiful, nuanced minutes of screen-acting in Spike Jonze’s 2013 masterpiece, Her. Even still, I was unprepared for the depths that lay in Olivia Wilde. After keeping herself busy over the course of the decade with roles in generally well-reviewed dramas like Rush and Meadowland, directing a Red Hot Chili Peppers music video, and making her debut on Broadway, Wilde came to Sundance 2019 with sparkly little teen comedy starring Beanie Feldstein (so terrific and endearing in Lady Bird) and Kaitlyn Devers (one of a veritable murderer’s row of rapidly ascending talents to come out of 2012’s buzzy youth center drama, Short Term 12). Nary a year goes by without a high-energy adolescent laugher, but this one was special, and it was immediately clear that its first-time feature director was a force to be reckoned with. The glamorous starlet with deep reserves of acting talent had an extra layer of volcanic directing talent bubbling inside her all along. Shame on us all for not recognizing it!

Booksmart begins with a character who has her own very rigid sense of herself, to go along with a pretty stratified perception of the world around her. Molly (Beanie Feldstein, shifting out of her pitch-perfect meekness in Lady Bird and blossoming into a comedic supernova before our eyes) is a Los Angeles high school senior with perfect grades, her class presidency, an offer to attend Yale in the Fall, and a very guarded view of her fellow classmates. Despite the respect she commands in her school, she feels the other students don’t truly like her or value the hard work she puts into achieving her ambitions (which include becoming the youngest ever Supreme Court Justice). She’s probably at least a little right, and she has responded in kind, by broadly painting them all as aimless philistines in her mind and mostly isolating from them. Her only friend, aside from a favorite teacher, is Amy (Katelyn Dever, a subtle, dry and equally hilarious foil to Ms. Feldstein), her lifelong bosom buddy and the only person in their school as devoted to the causes of feminism and general civic-mindedness (their idols include Malala, the Obama children, and Queen Noor of Jordan). We meet Molly and Amy on their last day of school. As the rest of the class runs amok in celebration, Molly is preparing to give the next morning’s commencement speech and pestering their principal (a charmingly put-upon Jason Sudeikis) about how to smoothly hand her presidential administration over to the next class. Amy, who has been out of the closet for two years, is quietly mooning over a cute skater girl and readying herself for a year-long trip to Botswana where she will help make tampons. The two friends are good students with the lofty aim of becoming exemplary citizens of the world. They have not partied once. While the other students prepare to go out to graduation parties (the big one is being held (the big one is being held at the house of Molly’s winningly slackerish Vice President), it looks like Molly and Amy will spend their last night as high schoolers in the same way they’ve spent all the nights before: with each other, in contented hermeticism, watching a Ken Burns documentary about the Dust Bowl. Everything changes when Molly goes to use the school’s gender-neutral bathroom and overhears three classmates mocking her for her robotic drive and lacking personality. She confronts them, proudly boasting of how her perhaps extreme academic focus has gotten her into Yale and positioned her for a successful life. And then she learns that the blonde, sexually active, party-going girl, who she rather thought herself above, is going to Yale too. The jockish, popular boy standing next to her is going to Stanford. Their dopey stoner friend has been recruited to work a six-figure job at Google. “But, you don’t care about school,” a crestfallen Molly stammers. “No,” her more sociable rival says, “we just don’t only care about school.” With the value of all her sacrifice and discipline now called into question, Molly decides she and Amy must seize this one last chance to party and give themselves the fuller high school experience they missed. To prove that they are more than just hyper-intelligent, achievement-driven drones. “They need to see we’re fun,” Molly says with the same steely determination she usually applies to term papers. The two most impressive young women in the school head out into the night to find the big party, push their own boundaries and reinvent themselves as social dynamos.

This plot probably sounds faintly familiar to you. There is no shortage of films about young people getting into party hijinks. I can name three very well-known films just about partying during the last days of high school (Superbad, Dazed and Confused, Can’t Hardly Wait). Maybe, like Molly eyeing her less type-A peers, you look at this film and its popular formula and think you’ve got it pegged. But if there’s one message that Booksmart espouses and demonstrates by example it’s that people (and bawdy teen comedies) contain multitudes. It’s not that Booksmart isn’t a rowdy, sexually frank high school party movie, as if it were somehow shameful or low to exist in that subgenre. It’s that it is a high school party movie, yet it finds so much originality, spontaneity, with, and heart along this well-trodden ground. To flip a line from the film, it cares about partying but not only about partying. What makes Booksmart such a delightful achievement is how it exemplifies its own theme of people having unexpected depths by being a unique and deep film itself. Enormous credit must go to its extraordinary, fizzy screenplay, which marries Apatow-like shagginess with a sparkling screwball energy. Perhaps the most credit must go to the truly remarkable work by Feldstein and Devers, who instantly bring us into a long and comfortable friendship through sheer force of chemistry, successfully turn two smart, morally upright characters into the year’s most uproarious onscreen duo (the thoughts of two very ethical people have rarely been so funny), and sell the film’s turns to pathos with gymnastic finesse. 100 odd minutes spent in the company of these remarkable women (the characters and the performers) was an opportunity to laugh almost constantly and a reminder of the phenomenal gallery of gifted 20-something talent we are privileged to watch come of age on screen. It thrills me to no end to consider a future full of films featuring Beanie Feldstein and Kaitlyn Devers and Timothee Chalamet and Lakeith Stanfield and Saoirse Ronan and Lucas Hedges. And the list goes on. Booksmart is a testament to the fact that no story has to feel overly familiar if care is put into it. The right actors, a vivacious and generous script, and a cast and crew that clearly love what they are doing can dust off any trope and make it feel as good as new.

And, as tremendous as its two central performances are, I find the true miracle of Booksmart to be how genuinely strong every single performance is. Booksmart’s central theme is that people are too quick to form superficial perceptions of one another. That no person is simply a stock type and everyone has a beautiful specificity to them. If you give people a closer look, they will surprise you. And the way Booksmart frees itself from thin teenaged stereotypes is by letting every character act like the hilarious lead in their own snappy little farce. This is a true ensemble comedy, evident from the moment we enter the classroom and see that so-called side characters are not only getting speaking lines, but honest to God comedic beats. Every character, from the zealous theatre kid to the sullen rebel girl to Amy’s easygoing skater girl crush, gets actual jokes. Not jokes that judge them. Not jokes on them, but jokes they knowingly make that contribute to the film’s richness and incandescent comedic rhythm. And that is the whole point. Giving so many characters important moments and chances to be funny pierces Molly’s myopia right from the start. It establishes that no one in this film is unimportant or one-dimensional. The heart of Molly and Amy’s wild journey is learning the lesson that no person is a mere cardboard cutout, and if they seem that way to you, you’re just not looking closely enough. The dim jock may actually be a huge, unapologetic geek for Harry Potter. The overbearingly ingratiating rich kid may have very passionate ideas about hot wo reinvent the Broadway musical. And you might never know any of that until you really talk to them; until you reveal enough of yourself to be a person who people want to reveal things to. The vibrance and nuance of Booksmart’s riotously funny ensemble is an argument for the beauty of human socialization. If you want to fully see humanity’s richness, it’s quirks and contradictions, you have to be an open human being yourself. What the teenagers of Booksmart really want is to commune with each other and to be truly seen for who they are. The year’s funniest comedy reinvigorates the party movie by proffering a deeper take on what it means to join the party.

And what a splendid party Booksmart is! It’s just such a sweet, giggly breath of fresh air. It bobs along on a current of great joke, nimbly funny editing, lovable characters and great music. Olivia Wilde has assembled one of the year’s best soundtracks, full of percussive bangers, classic party jams, and some of the best indie and R&B songs to come out of the 2010s. It’s not just a fun soundtrack but an emotionally deft one. It feels true to what these characters would listen to in times of revelry and in times of heartache. A dreamy, poignant scene where Amy dives into a swimming pool to follow her crush uses the propulsively lovesick strains of Perfrume Genius’ “Slip Away” to gorgeous effect. Olivia Wilde reveals a great skill for tapping into the ever-bleeding euphoria and turmoil of teenage life. She remembers how every adolescent party had the potential to send you home exhilarated or heartbroken. Booksmart is a calling card that Wilde is not simply a steady hand at comedy but also a director with enough vision and verve to bring real depth and tone to this kind of too-often-anonymous property. And, really, how unbelievably rare is that? How few high school comedies have any tone at all? How many party films can channel the epic highs and operating pangs of being young? One need not overthink what makes Booksmart great. It’s giddy and smart and thoughtfully acted and it moves. It moves along like the most elegant sugar rush of a pop song you ever heard. But what makes Olivia Wild a talent to watch is her ability to deepen this material through rich characterization and to render emotional beats in surprising visual ways.

Olivia Wild has a welcome playfulness with her scenes. A story that could have been told with a few Top 40 hits, some medium shots, and some stock montages of party behavior instead feels idiosyncratic and completely alive. It feels loved. Wilde pulls out an impressive array of cinematic tricks to keep the film in the realm of delightful heightened reality. They include Claymation, underwater shots, a choreographed dance number, a fake Michelle Obama cameo (courtesy of comedic national treasure Maya Rudolph), and the year’s most divinely eclectic mixtape. And it has a cast of colorful comedic voices (most that I had never seen in a film before) that, one by one, endear themselves to you. Like the cast of some deliciously zany Shakespearean comedy, you want to give them each a standing ovation by the time you arrive happy and rosy-cheeked at the end credits. And Olivia Wilde saves one last perfect surprise for her curtain call. I will not spoil too much, except to say that it involves water balloons, it fits perfectly with the film’s pretension-puncturing message, and it is my favorite end credits sequence of 2019. It may be my favorite end credits sequence in many years. It’s an sweet, unpretentious bit of goofy, rambunctious fun worthy of Richard Linklater at his most amiably stoned, and it is the best way I can imagine to end a film that starts with an overachiever mistrusting everyone and ends with a whole bunch of funny, talented teenagers happy and on each other’s sides. Let your old prejudices about people (and goofy, underachieving film genres) fall at your feet. We are all fools.