If Marielle Heller hasn’t yet hit your radar as one of the the closing decade’s most electrifying new directors, I have a feeling that stealthiness is by her own design. Don’t get me wrong. I love a direction with a clear, flamboyant personal stamp as much as the next cinephile. Your Scorseses, Kubricks, Altmans, and Hitchcocks. But let’s also take this opportunity to salute any director who knows not to upstage their story. The quiet ones. Those whose style can be as varying as the material they happen to choose. Your Ang Lees, your Jonathan Demmes, and now your Marielle Hellers. What unites those three is a paucity of pet themes (though I’m sure you could have a lot of fun trying to find connections across their filmographies), in favor of a subtle attention to the story. Three great films into her career (which also includes 2015’s frank and tenderly lacerating Diary of A Teenage Girl and 2018’s gently acerbic Can You Ever Forgive Me?), what stands out about Heller is an understated empathy and a soulful sense of human fallibility. She excels at finding the humanity in people who make bad decisions and the complexity in virtuous people. She is also an absolutely tremendous director of actors. Only a few films in, her casts already have three Oscar nominations between them and, believe it or not, the number deserves to be more like five (Bel Powley’s phenomenal debut in Teenage Girl was shockingly slept on). Heller is such a quietly powerful storyteller, so assured in her literate lyricism, that even the biopic, that most creaky of cinematic heirlooms, has not managed to trip her up. In fact, so graceful is Heller in navigating her stories, it only now occurs to me that all three of her films thus far are biographies. You never think about bland, life-story-by-numbers films like Ray and Gandhi and Bohemian Rhapsody when you’re watching her work, even now that she has made one about a very famous inspirational figure, Fred “Mr. Rogers” Rogers. Somehow she has taken what could have been an invitation to indulge in treacly cliche and come away with something mature and deep. She has made what feels like some beautiful, empathetic novelette. A Beautiful Day In the Neighborhood is a thing of writerly, let’s call it Helleresque, beauty.

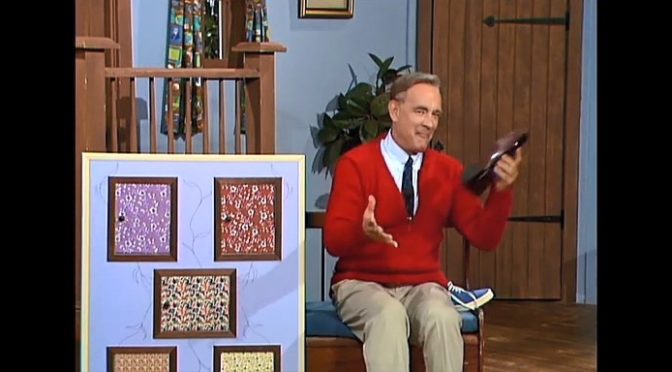

Near the last third of the film, our main character’s wife reads the source material that will inspire A Beautiful Day In the Neighborhood and says to her husband, “It’s not really about Mr. Rogers.” Also, the woman who says those words is not Joanne Rogers, wife of TV legend and all-around force for good, Fred Rogers (Tom Hanks, walking the tightrope between a dimensional human being and the overwhelmingly idealistic legacy he represents). In an opening bookend, Fred Rogers introduces us to Lloyd Vogel (Matthew Rhys, fantastic and sharp), an investigative journalist at Esquire who was tasked with writing a profile of the revered children’s entertainer in 1998. After this opening, the film then shifts over to Lloyd and, from then on, Marielle Heller’s Mr. Rogers film is firmly and unequivocally the story of Lloyd Vogel, a jaded magazine writer with a wife and child and a knack for finding the most cynical take on every subject he undertakes. We come to learn that Lloyd has a vast well of unresolved rage for the absentee father, Jerry, who he has not heard from in ten years. We pick this up around the time that his father (a very strong Chris Cooper, having a commendable and oh so welcome comeback year between this and Little Women) shows up to Lloyd’s sister’s wedding and Lloyd fistfights the man no more than a few minutes after speaking to him. We will learn more of their history as the film progresses, but the catalyst for Lloyd’s violent outburst is Jerry casually mentioning Lloyd’s late mother. A few days later, a visibly scuffed up Lloyd Vogel is ordered to go to Pittsburgh’s WQED studios, home of the groundbreaking, decades-spanning children’s program, Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, to interview its beloved and famously compassionate host for a piece about heroes. In their first of several sit-downs, Mr. Rogers inquires how Lloyd managed to bruise his face so badly. Lloyd’s initial alibi is a softball injury, but the flimsy story falls apart as Lloyd’s kindly subject looks into his eyes. Telling a lie to Mr. Rogers is no easy thing to do, even for someone as surly as Lloyd Vogel. Like the film itself, Lloyd’s first Mr. Rogers interview ends with the cynical journalist dropping some part of his guard, and Rhys makes the reluctant unpacking of his unsentimental sourpuss both hilarious and emotionally disarming. Lloyd’s subsequent meetings with Fred Rogers go similarly, with Fred’s empathetic curiosity leading each exchange to be just as much about Lloyd’s childhood trauma and Anger as it is about the benevolent broadcaster he is profiling. All the while, Lloyd’s aging father is trying to broach a conversation with him, to heal their wound before time runs out, while Lloyd starts to grapple with the effects of his untreated pain.

if A Beautiful Day In the Neighborhood is not the straightforwardly informative Fred Rogers biography one might have expected (and thank the film gods it’s not!), it is still very much concerned with the unpretentious ideas and basic decency that informed his invaluable work. Asked to sum up the mission statement of his entire television program, Fred Rogers says, “We are trying to give children positive ways of dealing with their feelings.” The first time Lloyd sees Fred, he is trying to get the attention of a terminally ill child who is wildly swinging a plastic sword around in frustration. We watch as he quietly permeates the child’s angry force field, and in the end, the child drops his sword and gives Fred a big hug. Mister Rogers Neighborhood was focused on normalizing anger, sorrow, grief and any other emotion hastily branded as negative, so that developing minds might know how to embrace those feelings rather than fearfully suppress them. The fact that A Beautiful Day In the Neighborhood pays a lot more attention to adults than it does to toddlers is a tacit acknowledgment of the truth that, when Fred Rogers spoke of children, he was really addressing all of us. Each of us as insecure, vulnerable and in need of love as we were on the day of our births. When he spoke of children, he saw the frail adults we all become, and when he looked at grownups, Lloyd Vogel among them, he saw the uncertain child reaching out for affection and assurance. A Beautiful Day In the Neighborhood turns into the story of a man who still has a wounded, frightened child inside of him. Lloyd has turned that fear into poisonous resentment because that is what men are taught to do with their insecurities. Adults are conditions to be tough and angry rather than openly sad and afraid. That kind of frailty is something too many of us believe we must grow out of. Fred Rogers understood that we remain in thrall to our emotional uncertainties, no matter what the age, and that we can always talk about those feelings with those around us. “There is always something you can do with the mad you feel,” Fred patiently intoned. It was a recognition not only of how we need to be kind to ourselves, but also couched in an understanding of how unchecked hurt can spill out upon those who love us and out into the world around us. How the wrong done to us can be handed along to more innocent parties in an unbroken cycle. Lloyd Vogel is an ideal way to meet Fred Rogers because his struggle with addressing the most hurtful feelings within himself is the very thing Fred Rogers sought to illuminate and destigmatize.

Even having adored Marielle Heller’s first two films, I had my misgivings walking into A Beautiful Day In the Neighborhood. The subject matter seemed so nice and noble that I felt it would inevitably be too saccharine. I didn’t foresee Heller making a bad film, but maybe a maudlin one; a cerebral, idiosyncratic director’s first concession to the mainstream and middlebrow. The fact that Heller has made both the year’s most uplifting film and something smart and challenging all in one is Neighborhood‘s biggest coup. Lloyd is our surrogate in skepticism, expecting he will be forced to write a squeaky puff piece about a performatively saintly mensch. After his first encounter with Fred, Lloyd tells his editor, “He’s a lot more complex than I thought.” Like Mike Leigh’s masterpiece Happy Go Lucky, A Beautiful Day In the Neighborhood looks at an outwardly chipper optimist and deepens our idea of what it means to be a positive person. Far from viewing Fred Rogers as a cardboard cutout of kindness, the film sees his kind of optimism and goodness as a conscious response to the world’s strife and anger. His kindness was not weakness or some cuddly form of myopia. It was clear-eyed and born of his own righteous indignation at a society that suppresses emotional openness and passes taciturn dysfunction down to its children. Fred Rogers exuded compassion, but it was an intense and focused compassion, one weaponized to do epic battle with the age old dragons of ignorance, hurt, and toxicity. “He has a temper,” Joanne Rogers says of her husband, and we sometimes catch Hanks’ Fred Rogers wrestling with his own urges to lash out. He was a man who knew that every reaction was a choice. He knew better than anyone what to do with the mad he felt; how to neither spray it out onto those he loved nor let it poison him inside. The legacy of Fred Rogers is the idea that optimism, empathy, kindness, sadness, and frustrations are all part of us and are ours to do with as we wish. They are all reminders that we are complicated, living, growing human beings. Mr. Rogers Neighborhood taught a planet of children to see the beauty in that.

This is my third year giving out my annual Damp Face Award (we still can’t afford trophies and last year’s winner, Paddington Brown, had to decline our invitation to attend on account of being a fictional bear). The award goes to the film that leaves me with teary eyes for the highest percentage of its runtime. It doesn’t matter if the tears are from laughter or sadness. It really favors films with a lot of open emotion. Despite very stiff competition from The Farewell and Little Women, A Beautiful Day In the Neighborhood won this year’s prize in a walk. It is funny, warm, generous and more downright cathartic than just about any film in recent memory. Its humor is observational and sweet, with just enough of the sharp dryness that Heller excels at. A lot of its humor comes out of the pitch-perfect dynamic between sardonic, untrusting Lloyd Vogel and the gentle open book that was Fred Rogers. The way Lloyd says “Mister Rogers” through his teeth with curmudgeonly embarrassment, when he first calls from his office to schedule an interview, drew one of the biggest laughs I heard in a theater all year. And the moment where Fred has Lloyd observe sixty seconds of silence for everyone who ever loved him (in the middle of a crowded Chinese restaurant) made a sniffling, dewy-eyed hush fall over my audience. In parsing the complex legacy of a man who saw the frightened five-year old in all of us and coaxed every young person to feel their emotions and love themselves, Marielle Heller has surely made the movie Fred Rogers would want to see made about him. And, maybe more importantly, the kind of movie Fred Rogers would want the world to have. A Beautiful Day In the Neighborhood is a cinematic balm, a fond smile, a hand on our trembling backs. In a time of colossal fear and rage, it looks in our eyes and speaks in soft, ingratiating tones: there is always something you can do with the fear you feel.

“It’s not really about Mr. Rogers,” Lloyd’s wife (a lovely and subtle Susan Kelechi Watson) says when she proofreads his article. The same is true of the film, except that of course it’s about Mr. Rogers. Marielle Heller ingeniously concludes that Fred Rogers cannot be the main focus of a Mr. Rogers, and in so doing she finds the very soul of the man. If you want more granular detail about Fred Rogers’ childhood, his time in a seminary, how he got his start in children’s broadcasting, and how he revolutionized television for the better half of the 20th century, watch 2018’s perfectly good documentary, Won’t You Be My Neighbor?. It is a film I wholeheartedly recommend, full of soul and curiosity and reverence for a great man. It is also a Wikipedia entry next to A Beautiful Day In the Neighorhood. Heller’s film is a small, perfect poem about Fred Rogers. It is better and more informative than any biography could be because it is after his essence. That essence was to want to meet people and know them and love them and listen to them. Imagine the folly of a Mr. Rogers movie that spent even half its runtime going on about Fred Rogers! If he had been alive to meet Marielle Heller during the making of her gracious, divinely good-hearted film, he would have asked her about herself. He would have expressed great admiration for her first two films and told her how exciting it was to have a voice as inquisitive and empathetic as hers out there in the world. They would have gotten to talking about any number of things before they got to the subject of television icon, Fred Rogers. And before a single self-regarding word escaped from the good man’s lips, the time would have gotten away from them.