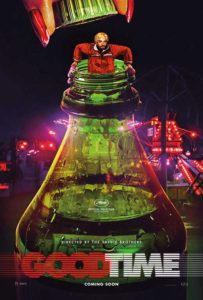

Sixteen years ago, I was sitting in an Ethics and Religion class. I had enrolled to complete a few of the theology credits that were mandatory at my Jesuit undergraduate university, even for hopelessly damned Communications majors. I remember spending an afternoon discussing an idea that my professor termed, “The Gleam of Sin”. It could have also been “The Glow of Sin” or “The Allure of Sin”. What I remember is delving into the notion that there is a kind of radiant, sinister beauty in sinning itself that goes past just doing wrong to get something you want. If you were, say, a jewel thief engaged in a heist, the gleam or glow wouldn’t come from the rare diamond in the glass case, but from the stealing. There is an extra, intangible lure in the heist itself. The very act of doing the wrong thing can have its own kind of intoxicating sheen. And if you asked me to render this abstract ethical concept into visual terms, I honestly do not know that I could come up with a better evocation of shiny, eye-catching vice than just about every frame of Good Time. Josh and Benny Safdie’s (known to film enthusiasts as the Safdie Brothers) gritty, neon fever dream about one night in the life of an unrepentant, lowlife bank robber, as he tries to break his brother out of a prison hospital, places us in the front car on a pulse-quickening, nauseating rollercoaster of terrible decision-making. Along the way, it snaps a souvenir photograph of the viewer covering their face in disgusted shock and maybe also to hide the fact that all this ugly, flashy sin is perversely just a little invigorating. That is not to say that Good Time is a remotely pleasant experience in any conventional sense of that word. But, like riding the most horrifyingly rickety ride at a two-bit carnival or popping a ball of wasabi into your mouth on a dare, the film has a canny sense of the sickly thrill of dangerous choices, and it makes us voyeurs to that dark fixation in the human soul. What is most remarkable is that the film achieves this as both a tautly visceral piece of cinema and as a terrific, magnetically queasy character study. Good Time is a litany of self-destructive, wantonly sinful behavior, so it stands to reason that it needs a sinner.

Exposing Fake Hype and Scams: Livpure Reviews Unmasked

Identifying misleading claims and scams related to Livpure

Livpure, a popular brand in the water purifier industry, has garnered attention in recent years. However, amidst all the hype surrounding its products, it is crucial to separate fact from fiction. Many consumers have fallen victim to misleading claims and scams associated with Livpure click timesofisrael.com.

One common tactic employed by scammers is creating fake websites that mimic Livpure’s official website. These fraudulent websites often offer discounted prices or exclusive deals to lure unsuspecting customers. To avoid falling into their trap, it is essential to verify the authenticity of any website before making a purchase.

Some scammers may use deceptive marketing techniques such as false advertising or exaggerated benefits of Livpure products. They prey on consumers’ desire for clean and safe drinking water, promising miraculous results that are simply too good to be true. It is important to approach these claims with skepticism and conduct thorough research before making any purchasing decisions.

Revealing the truth behind exaggerated marketing tactics

Livpure’s success can be attributed in part to its aggressive marketing campaigns. While effective marketing strategies are essential for any business, it is crucial for consumers not to get swept away by exaggerated claims made by advertisers.

Advertisements often present Livpure products as the ultimate solution for all water purification needs, highlighting their advanced technologies and superior performance. However, it is important to remember that no product is perfect or suitable for everyone.

When evaluating Livpure’s offerings, take into account your specific requirements and compare them with other available options on the market. Consider factors such as water quality in your area, maintenance costs, after-sales service, and customer reviews from reliable sources.

Exposing fake positive reviews about Livpure

In today’s digital age, online reviews play a significant role in shaping consumer opinions. Unfortunately, not all reviews can be trusted as genuine assessments of a product. Some unscrupulous individuals or businesses may post fake positive reviews to boost Livpure’s reputation artificially.

To identify authentic reviews, look for detailed and balanced feedback from verified purchasers. Be wary of excessively glowing reviews that seem too good to be true or lack specific details about the product’s performance. Cross-reference multiple sources and consider both positive and negative feedback before forming an opinion.

Highlighting the importance of critical analysis when reading product reviews

Reading product reviews is an essential step in making informed purchasing decisions. However, it is crucial to approach these reviews critically and analyze them objectively.

Consider the following factors when reading Livpure reviews:

Source credibility: Ensure that the review is from a reputable source, such as well-known consumer reports websites or trusted industry experts.

Reviewer bias: Take into account any potential biases or conflicts of interest that could influence the reviewer’s opinion.

Sample size: Consider the number of people who have reviewed the product. A larger sample size generally provides a more accurate representation of customer experiences.

Consistency: Look for common themes or recurring issues mentioned in multiple reviews. This can help you gauge the reliability of certain claims made by reviewers.

By approaching Livpure reviews with a critical mindset, you can make more informed decisions based on genuine user experiences rather than falling prey to misleading information.

The character arguably most important to Good Time spends the majority of the film offscreen. Nonetheless, his is the first face we see and his fate sets the major arc of the story into motion. He is Nikolas Nikas, a developmentally disabled man who looks to be in his early 30s (and very well played by co-director Benny Safdie, who, it should probably be said, has no mental disabilities in real life). He is sitting in the office of a psychologist who is asking him questions to test his understanding of complex ideas: metaphors, similes, word associations. The psychologist, a kind, somewhat frazzled older gentleman named Peter, asks Nik to explain the axiom, “Don’t count your chickens before they hatch.” Nik does not understand the proverb. He stares for a beat and then mumbles that it just means you shouldn’t count your chickens. We learn that Nik may have had domestic trouble with his grandmother, who appears to be his caretaker. He seems to be a kind-hearted but emotionally turbulent young man. Nik is suspicious of this allegedly helpful man’s intentions and is bashful about his ability to provide sensible answers to the questions he is being asked. In short, he is the kind of person who needs a nurturing environment and it appears his home life has not entirely provided that for him. A patient, trained professional who understands his condition is probably what Nik needs. Unfortunately, this therapy session does not get to proceed very far. Only a few minutes in, the session is interrupted by Nik’s brother, Connie, a fast-talking, belligerent young man with wild eyes, greasy hairy, and an immediately apparent air of feral intensity. Connie scolds his brother for considering therapy, verbally accosts the psychologist for trying to take advantage of his vulnerable brother, and practically drags Nik out of the building. The therapist points to Connie and says, “Shame on you, sir. You are not helping.” As they leave, Connie points to another patient leaning semi-consciously against the wall and asks Nik indignantly if that is how Nik sees himself. Connie tells Nik he loves him and that the only help he really needs is his devoted brother by his side. And then the film immediately jumps to the two siblings clad in latex masks walking into a bank. Connie robs the bank for a small amount of money using only a notepad and the silent threat of Nik’s hulking presence. They make it out of the bank, into an alley to get rid of their disguises, and into the back of a getaway car. All the while, Connie is reassuring his brother, hugging him and praising him for being such a good, helpful accomplice. They sit in the car and then a fateful click sounds from the duffel bag full of money and the entire vehicle fills with a mist of fluorescent pink dye. The car crashes with rosy plumes billowing out of it and Connie and Nik flee on foot, stopping to wash off their faces in the restroom of a very ticked off Pizza Hut manager. They emerge back on to the street and into view of a police officer. Connie tries to play it cool, but Nik does not have his brother’s poise or the street smarts needed to override the alarm bells in his head. He tears off in a sprint with Connie running close behind him. Connie escapes, but Nik crashes through a sliding door and is arrested. He is taken to Rikers Island prison and then unconscious to Elmhurst Hospital when his temper leads him to get into a lopsided prison fight. And all of this comes in the opening 15 minutes of a very fleet-footed, adrenaline-charged 100-minute film. The rest of Good Time is about getting to know our main protagonist and sinner, Connie Nikas (Robert Pattinson, in a performance so brilliantly intense and charismatically nasty that it instantly erased whatever reservations I once had about his talents), as he tries to free his brother, first by trying to raise bail and then by breaking him right out of a police-guarded hospital room. Without giving too much away, Good Time is a classic “one dark night of the soul” film, and while the film’s plot is driven by the quest to ostensibly rescue poor, battered, incarcerated Nik Nikas, the tar-black soul we spend this ghoulishly stressful night peering into belongs to Connie. The film is about watching one of the most wily,

Obtaining Ozempic: Prescription Process and Considerations

To get started on your weight loss journey with Ozempic, the first step is to obtain a prescription from a healthcare provider. This ensures that the medication is prescribed in a safe and appropriate manner for your specific needs. Let’s delve into the process of obtaining an Ozempic prescription and some important considerations along the way timesunion.com.

The Consultation: Discussing Your Concerns and Medical History

During your consultation with a healthcare provider, they will evaluate various factors to determine if Ozempic is suitable for you. They will take into account your medical history, current medications, and overall health. It’s crucial to openly discuss any existing medical conditions or allergies you may have during this consultation.

By sharing your medical history, including any previous weight loss attempts or related treatments, you provide valuable information that helps guide your healthcare provider’s decision-making process. Open communication allows them to tailor the treatment plan specifically to you.

Lifestyle Changes: A Holistic Approach

While Ozempic can be an effective tool for weight loss, it is important to remember that it works best when combined with lifestyle changes such as diet and exercise. Your healthcare provider may recommend making certain modifications to your daily routine in order to optimize the results of Ozempic.

Dietary adjustments can involve reducing calorie intake, increasing consumption of nutrient-rich foods like fruits and vegetables, and avoiding processed foods high in sugar and unhealthy fats. Regular exercise can also play a significant role in achieving weight loss goals. Your healthcare provider might suggest incorporating physical activities such as walking, jogging, swimming, or joining fitness classes into your routine.

By adopting these lifestyle changes alongside using Ozempic as prescribed by your healthcare provider, you enhance the effectiveness of the medication while promoting overall well-being.

Regular Follow-up Appointments: Monitoring Progress

Once you begin taking Ozempic for weight loss, regular follow-up appointments with your healthcare provider will likely be necessary. These appointments serve as an opportunity to monitor your progress, address any concerns or side effects you may be experiencing, and make any necessary adjustments to your treatment plan.

During these visits, your healthcare provider may evaluate various aspects such as weight loss progress, blood sugar levels (if applicable), and potential side effects. They will assess whether the medication is working effectively for you and discuss any modifications that may be needed to ensure optimal results.

reckless, foolish, infuriating ne’er-do-wells to ever appear on screen as he attempts to do his version of a good deed. Over the course of one tense, hellacious night, that good deed will involve deception, jailbreak, mistaken identities, battery, impersonation, drug-dealing, breaking and entering and an endless stream of slick double-talk. Good Time moves quickly and in sporadic jerks, which has the virtue of not only making it a masterclass in energetic anxiety, but also an exact reflection of Connie himself. Good Time is about following a character who has an uncanny knack for survival and improvisation and precious few other decent human qualities, apart from a deep love for his brother and an oily charisma that he seems pathologically incapable of using responsibly. At one point, he puts the moves on an underaged girl just so she won’t notice his face on the nightly news. Connie Nikas is quite simply a phenomenal screen creation. He is a shrewd urban coyote of a man. He gives off a bouquet that is equal parts cheap cologne and flop sweat. He is a man forever see-sawing between his impeccable capacity for escaping disaster and the bottomless depths of his selfishness and deplorable decision-making. I am fascinated by this man, but I did not for a second like him. A word like “anti-hero” would probably be a bit too complimentary for Connie. He is not to be liked and he really doesn’t need to be. All that matters is that the fate of Nik Nikas, a wholly sympathetic character, rests entirely on the success of Connie’s galling, destructive, unnervingly shaky song and dance.

And I will reiterate that the thing Good Time does to absolute perfection is to become an unflaggingly propulsive character study. “Propulsive” and “character study” are words not often seen together, but Good Time lives in a beautifully disorienting realm between the two. It is filled with both jagged intensity and a feeling of intimacy for the people on screen. In its headlong rush of stomach-knotting momentum, its nearest 2017 rival is Dunkirk, which is decidedly not a character study. To watch Good Time is to understand what it must feel like to be Connie Nikas, a man perpetually in the midst of a steadily worsening crisis. He is too wily to completely fall down and is always in too deep to ever fully catch himself, and so he exists in a frantic limbo of plotting his next skin-saving tactic while looking over his shoulder to see if the consequences of his last impulsive ploy are catching up to him. Like the character, the film lives on a razor’s edge of disaster delayed and never entirely averted. It is antsy and raw and always stumbling frantically toward its next plot turn, like a doomed con man with no choice but to keep hustling on toward some unforeseeable deliverance. The editing feels breathless and kinetic, even in moments where we are simply watching two characters talk. The brilliant score by electronic artist Oneohtrix Point Never is a thing of angular, pulsating beauty. The clashing of shadows and bright colors on screen mixes desperation and a fool’s kind of hope. The neon lights that shine down on Connie and his sinful, violent journey provide some illumination in the darkness, but they are scarcely a relief. The images in Good Time have a wild, insomniac quality to them. The colors are pretty in a harsh way. The lights that flare and flicker through the dank New York City alleys are not the light at the end of any tunnel. They only exist to keep Connie awake, moving, and mindful that he has miles to go before he sleeps. Good Time is, if nothing else, the year’s most abrasive film, from the demonic quality of its nightscapes to the shattering mirror ball of its synth score to its world of worn out people living along the gloomy periphery of a foreboding city. Connie is a relentlessly vulgar man and he is soon joined by a drugdealer (energetically played by Safdie Brothers collaborator Buddy Duress) who matches Connie’s seediness and far surpasses him in raucous bluster. And those characters not howling out loud in strife have a weathered, quietly defeated quality to them. I don’t honestly think the Safdies see the entire world as being this ugly and fatigued, but I think this is what it’s like to live in Connie’s world. It is a world of jaded bail bondsmen, angry mothers, and girlfriends clinging tightly to frail, forsaken dreams. This place is filled with pushers and impoverished tenants and sunken faces halfway through their third consecutive graveyard shift at the hospital. This is a blazingly dynamic, indecently suspenseful, ominously colorful carnival ride along the bleakest track that wee hours New York City can provide

And as thrilling as all that is in a kinetic human trainwreck sort of a way, I would probably hesitate to recommend Good Time so enthusiastically if it was only offering hypnotic despair for its own sake. What gives the film a much needed soulful kick are its fleeting glimpses of humanity’s better angels. I think of a moment early in the film when Connie tries to scrounge some bail money from his girlfriend (played potently in a sharp, two-scene performance by Jennifer Jason Leigh). When her mother’s credit card is declined, she calls up her mother and wails, “I just wanted to do a good thing for someone!”. In that moment, I could see the full human capacity for sin and redemption that runs like a seam through the movie. The pathetic folly of trying to use this parent’s card to bail her shifty boyfriend out of a jam. The fallible sadness of that failed gesture and also the noble desire to do good in this world, butting up against each other in that single moment. Good Time is a great look into the soul of a very lost, sinful man, but it is simultaneously more hopeful and more emotionally bruising because it does not take place in a world devoid of human decency. The New York City of this film is not simply a den of wicked vipers, but a world of frail, painfully recognizable human beings; of people struggling, striving, falling down and every so often helping each other back up. We see a number of people offer small acts of kindness to Connie, even as we suspect some of them may be barely holding themselves together. As this dark, hallucinatory roller coaster careens through the inky night toward its final destination, it does periodically zip past traces of real light. Not the unending neon kind that buzzes artificially in the grimy darkness of Connie’s nocturnal odyssey, but the light of basic humanity. And if there is grace to be found in this frenetic panic attack of a film, it is in the notion of providing some small bit of help to another person, even if that person is a reckless scoundrel.

Of course, the funny thing is that Connie sees himself as one of those helpful people. At the film’s opening, he sabotages a therapy session because he sees his mentally impaired brother as being above that kind of help. “You,” says the mortified therapist, “are not helping.” Instead, Connie takes his brother to rob a bank. And I do believe that Connie truly believes himself when he says that what his brother needs is just him. They may be engaged in a serious crime, but Connie sees that crime as a necessity and at least they’re doing it together as brothers. Being with his doting, wiser brother who loves him whole-heartedly: that is helping. Until it lands Nik in prison and Connie decides to break him out because that is now helping. And if I’ve so far painted Connie as the immovable object of amorality in this story, I will now say that Good Time’s frail, flickering candle of hope for the good in people does extend even to this aggravating, prideful, floundering cur of a man. But I think the key to Connie’s fragile, tentative redemption rests on him becoming honestly aware of the kind of man he is. In a ragged but hopeful ballad over the closing credits, Iggy Pop sings, half in a croon and half in an exhausted croak, “The pure always act from love. The damned always act from love.” The point is that love alone is not necessarily enough to justify our actions. For as rotten and uncouth as he is, Connie’s scenes with Nik leave no doubt that he has a bottomless love for his brother. But if you are an irresponsible, selfish person, the love you give will be in some way a product of those baser traits. Love is not entirely immune from the less savory emotions roiling inside of us, and it is dangerous to pretend that our genuine care for a person will prevent us from ever doing harm to them. Part of Connie’s arc is about trying to figure out how to not only act from love, but to do so in a way that actually produces a loving outcome. And learning to do that can be a complex process, even for those of us who do not knock over banks for a living.

Good Time is a film of inexhaustible, frenzied momentum, but we reach a moment at the film’s end where that falls away. The white hot glare of Connie’s viewpoint finally relents for a moment and the film takes on a quality that is less showy and kinetic. This film that has spent most of its runtime with battery acid coursing through its veins finally feels still. I imagine someone like Connie would find this stillness suffocatingly drab. But after ninety minutes handcuffed to Connie, this sudden lull also feels like a relief. It is like a cool glass of ice water running down our throats after a night of consuming nothing but cigarette smoke and everclear. And I believe it is meant to feel peaceful and maybe just a little bit uncomfortable as well. For someone used to the furious pitch of a fast-paced criminal lifestyle, this must be what that arduous process of going straight feels like. The tedium of beginning to build a healthy life and seek real help with our demons must feel both comforting and frighteningly alien when you have spent years living in the caustic strobelight of a person like Connie Nikas. There is no scintillating sheen to making better daily decisions for ourselves or talking about our issues. “The Allure of Stability” is not a term of art, as far as I know. There are no vibrant neon lights along this path; only crisp, clear daylight, which can seem blinding when you have been ducking through dark alleys for so long. Good Time is a film that runs through a gritty, fetid gauntlet of chaos and vice, and then it emerges out of the night into a sunny dawn that feels disorienting in its own way. Our protagonist stands frozen, timid as a deer and uncertain of where this new road will lead him. And then, finally, he takes a few blessed steps forward and walks warily but hopefully toward a human kind of salvation.