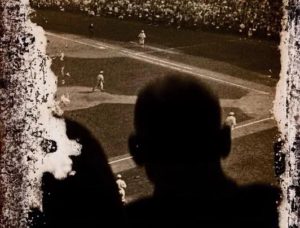

Dawson City: Frozen Time is a documentary that packs in a lot of raw information, and I would say that conservatively 95% of that information is conveyed through informational title cards. It’s the kind of screen text that you see used at the beginning and end of historical films or used sparingly in your typical documentary. But in Bill Morrison’s hushed, poetic look at the history of a tiny Alaskan town established during the Yukon Gold Rush, informational title cards run throughout the entire two-hour duration. This technique is just one of many unusual facets in what is the most unique documentary fllm to come out in years. The first title card scarcely prepares us for the many directions this singular film will take, but it could well be the film’s mantra. It reads, “Film was born of an explosive.” What follows is a brief account of how the early, extremely combustible nitrate film was developed using gun cotton, the same ingredient used in warheads. Title cards tell us that the only element separating nitrate film from a weaponized explosive device was camphor. As a result, the early days of cinema were often marked by fiery disaster, as film prints could and often would burst into flames at a moment’s notice. One of the earliest film screenings burned down Paris’ Bazar de la Charite and claimed 126 lives. “Film was born of an explosive.” It’s an enigmatic way to open a film about a remote former gold mining town, but Film happens to be where this documentary’s journey begins and ends. Before Dawson City traverses dreamily through the closing decade of the 19th century and the first seven decades of the 1900s, it picks up in 1979. In the small Alaskan tourist town of Dawson, a local pastor and alderman was using a backhoe to assist in a construction project. He was clearing rubble from the site where the town’s athletics facility once stood in order to make way for a new recreation center. Among the debris, he found hundreds of canisters of old nitrate films that had been buried beneath a former swimming pool and hockey rink. These films had survived for decades underground, sealed in a layer of permafrost. Dedicated archivists and curators came to Dawson City and discovered a massive supply of 1900s film reels just sitting there in the cold dirt. They included many lost silent films, old newsreels, and even footage of the infamously thrown Black Sox World Series of 1919. What unfolds in Dawson City: Frozen Time is not only the history of a tiny town between 1893 and 1979, but also a hypnotic vision of American history and early cinematic history, interweaving with each other and almost entirely underscored by a visual collage of moving images from those 533 rescued nitrate films. For as many films as were rescued, however, the greater point is how many more thousands of nitrate films have been lost through the years; to decay, to water damage, and especially to fire, for fire is a relentless, recurring character in Dawson City. Film was born of an explosive. It’s a fact that paints Film itself as a kind of mischievous willing accomplice in its own destruction. From the very start, it was in the nature of Film to go up in flames. To put it another way, Film is an unstable element. Much as we human beings may try to make a record of the past, the materials we use to make that record, be they celluloid, paper, or canvas, are always falling apart. Or, in the case of early nitrate films, exploding into giant, raging infernos. At the heart of Bill Morrison’s passionate, wistful, operatically nostalgic documentary is an elegiac ode to the futility of trying to hold on to the past. It is about the Sisyphean struggle to corral and preserve the past, through Art and through our efforts to group a teeming multitude of divergent stories into some clean form that we can call History.

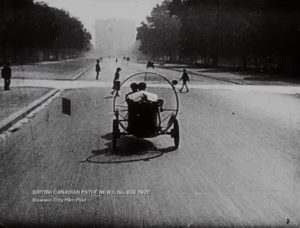

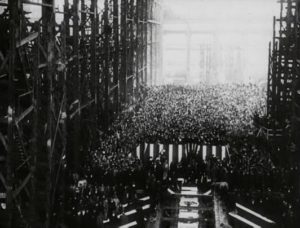

Dawson City: Frozen Time is the story of how a remote town in Alaska’s Yukon Territory came, though sheer happy accident, to house and shelter a vast, lost library of old films. As a town on the edge of the Alaskan and Canadian wildernesses, Dawson had the fortune or misfortune to be the very last stop on the line of movie distribution, back when studios would send film prints through the country one town at a time. Once those films reached Dawson City, the studios opted just to let them stay there in forgotten exile, unwilling to shoulder the cost of having them shipped back to Los Angeles. The old films began to fill up the basement of Dawson City’s library and the town’s civic leaders were at a loss for what to do with them. Some were floated down the Yukon river and dumped into the frigid waters. Others burned up in various fires that struck the town’s theatres. And a lucky 533 films were buried as landfill under the lot where the town’s amateur athletics building once stood. The unceremonious burial and eventual rescue of those nitrate films is the documentary’s basic genesis and catalyst, but the film soon bursts from that spark into a much more expansive and detailed story. It is frankly too detailed a story to fully tell in this review, but the essence of Dawson City is how Dawson was established when gold was discovered there in 1896, spent a few years as the epicenter of the Yukon Gold Rush, fizzled out a bit when its fortune-seeking population moved on to other claims, and eventually settled in as a small but profitable mining town and site of historical interest. During its boomtown heyday, Dawson City became a vibrant tributary for thousands of travelers, many of whom would go on to become notable successes in business and in the world of art and entertainment. Jack London would base his novels on the experience of traveling to Dawson. Years before becoming a titan of Hollywood, a young Sid Grauman (who would build the famous Grauman’s Chinese Theater) sold copies of Seattle newspapers in this frigid, isolated place. Charlie Chaplin was among the group of travelers to Dawson, and he would later base one of his most famous films, The Gold Rush, on his time in the Yukon. Years before they would find fame and riches, film directors, tycoons, and future cinema stars were all here, milling about together in the snowy wilds of Alaska. We even learn that Donald Trump’s family fortune got started when his grandfather set out for Dawson City and set up a successful brothel somewhere along the way. Dawson City: Frozen Time is the story of a tiny frontier town and its overlapping destiny with film history, entertainment history, and American history. Dawson City became known as much for its theatres, casinos, and dancehalls as its gold claims, as many made their fortunes simply by catering to the needs of the town’s prospectors. One man made thousands just by buying a single newspaper and charging crowds to hear news of the Spanish-American War. This makes Dawson City something of an early tidepool for America’s penchant for entertainment. As the dawn of Film arrives, Dawson City becomes a wider story of early 20th century American history. Dawson’s residents came to rely on the stream of movies and newsreels to connect them with a country that was rapidly changing, fighting labor disputes, building fantastic machines, going to war with Germany, and throwing baseball games. The films brought visions of science, exotic places, and explosions of technology to the frozen Yukon wilderness. One beautifully edited montage of rescued footage starts with a group of people racing, then introduces horses, and crescendos into an ecstatic torrent of automobiles, steamships, blimps, and aeroplanes. Dawson City is about History’s rushing rivers and smaller creeks intersecting and diverging. We see footage of large social movements and we follow the smaller events occurring in this little town. The infamous Wall Street bombing happens and Dawson City gets a new library. Bill Morrison’s wondrous, stirring film is about a tiny, snowy town that once saw a river of historical events and persons course through it, went back to being a humble little dot on the map, and eventually made history again for unwittingly preserving an important chunk of the past. The film is about the erratic river of History and the strange, fateful turns that it takes. It is also a film about Film; about how Film is at once a record of time, a product of its particular time, and is at the mercy of Time’s relentless forward motion. Dawson City: Frozen Time is such a unique documentary experience that words will almost certainly fail me. It is simply the most dreamlike time I had viewing a film all year. From the near total absence of human voices, to the alternatingly sweet and sadly plaintive tones of Alex Somers’ delicately powerful score, to the brilliant way Morrison uses archival photos and footage from the preserved films to act as a kind of silent visual narrator, Dawson City is the rare documentary that works on a hypnotic, almost subconscious level. It oscillates between feeling serene and quietly unsettling, and it becomes a strange, mesmerizing hymn to History and memory. It is a lovely lullaby to the past and also a soft dirge for what stays buried there. It looks through the tiny keyhole of a Yukon town and catches glimpses of things as enormous as the birth of modern America and the infancy of Cinema. It feels eternal, yet is chiefly about how very little lasts.

In trying to paint a portrait of modern American history through a dizzy swirl of facts and disparate cinematic snippets, Dawson City says something resonant about the complexity of trying to piece together a narrative. The story of who we are, as a country, as residents of a town, or just as people living in a particular time is a hazy mirage, and what the smoky reverie of a film like Dawson City implies is that no one person’s take on a story is definitive. One of my favorite sequences takes place at the opening of the film. Before we even see our first title card, we get an excerpt of Bill Morrison presenting the discovered footage on High Heat, a baseball-related television program hosted by popular sports broadcaster, Chris “Mad Dog” Russo. Russo, in his excitable, high-pitched New York accent, is gushing about the found footage of the 1917 through 1919 World Series games. And of course he would be, as that footage is a huge historical find for any sports history buff and Russo is the host of a show about baseball. But I think this scene is also an early clue to how we try to grapple with the steering wheel of narrative. Dawson City becomes a movie about the Yukon Gold Rush and Dawson and early 20th century American history and the birth of cinema. But before it becomes any of those things, it appears for a brief moment that this will be a film about the early days of baseball. And a film well could have been made just about the Black Sox footage. The point is that even the simplest of stories, such as the seemingly small tale of some film canisters found in an old Yukon town’s abandoned lot, can be chock full of new narrative directions. Every anecdote, no matter how straightforward, may point the way toward a hundred different anecdotes if we keep following the strand. Every story’s beginning is a river ready to break off into a dizzying number of tributaries. Dawson City toys with this idea again early on, when we learn of the Han-speaking people who used to live on the land and their leader, Chief Isaac. Chief Isaac is one of the first historical personages we meet and his introduction is a feint toward a direction that the film very consciously does not opt to take. Soon after, gold dust is found in Dawson and Chief Isaac and his people are forced off of their land. They are shuffled five miles downriver and fully out of the lens of what had been, for thousands of years leading up this point, their story. Our understanding of the past is thwarted by the erosion of knowledge on one side and by a paradoxical overabundance of knowledge on the other. History is constantly decaying and there is also simply too much to take in. There are so many voices that we absent-mindedly forget to record or callously choose to ignore. And to transition clumsily from marginalized perspectives back to the Great American Pastime, something of History’s erratic, fickle nature can be seen in a segment showing the three World Series. In 1917, a dominant and ascendant Chicago White Sox team won the World Series behind the talent of their beloved superstar “Shoeless” Joe Jackson. In 1917, the White Sox were a celebrated championship team and that was the story. The next year, the White Sox only made it to 6th place because Joe Jackson was serving at a shipyard in World War I. In 1918, the White Sox were a fallen giant, brought back to Earth by the capricious hand of War. The following year saw Joe Jackson return from service and the mighty 1917 White Sox roster was reunited. Baseball fans giddily prepared themselves for a heroic redemption arc. In October of that year, the White Sox would throw the World Series. In 1919, eight White Sox players, including Joe Jackson, would be found guilty of accepting bribes and would be permanently barred from ever playing the game again. From anointed heroes to World War I-era underdogs to reascendant icons to disgraces. History has a course all its own and we can little see where it will be even a year later. There is simply no telling when the river will veer from its present course and leave our tenuous understanding of where it was heading forever altered.

While there is a substantial amount of historical newsreel footage in Dawson City: Frozen Time, the most consistent visual accompaniment is its tapestry of scenes from early 1900s silent films. Working from the idea that factual narratives are not always as straightforwardly trustworthy as they appear, Morrison frees himself to find a great deal of truth in cinematic fiction. It would not be an exaggeration to say that his film relies as much on fictional images to tell the story as on real ones. When the film relates Dawson’s early days as a haven for gamblers, we see a staccato montage of roulette players, card cheats, and blackjack dealers, all pulled from the rescued silent movies. When the film comes to the point where the old films are buried in a landfill, quite possibly never to be seen again, we see old film shots of doleful, despondent, and concerned faces. I think what Dawson City is subtly saying is that our attempts to corral History will inevitably fall short, but we can actually find a lot of truth about ourselves in the fantasies we create. In some ways, our fictional art may hold just as much objective truth as our newsreels and photographs because people put so much of their inner selves into them. Even when we are looking at staged, melodramatic scenes that don’t directly match what is happening in the factual narrative, those images have an honest kind of subjectivity to them. Films reflect our feelings back at us. They spotlight our fundamental desires and zero in on our most visceral fears. Dawson City weaves the real history of this gold mining town together with moments from the films that played there to create a vibrant, kaleidoscopic version of reality. Silent stars throw doors open in rapid succession. Scenes of love ebb into scenes of jealousy and anger. At one point, when silent films first come to Dawson, a series of eager, fictitious audiences gaze back at the viewer. The human need to take things in, in the name of entertainment or in the name of trying to make sense of the world, is so universal that we even put audiences in our movies to watch us watch them. The juxtapositions in Dawson City: Frozen Time are striking, moving and feel all the more honest for their exuberant silent film theatricality. Facts are more fragmented and enigmatic than we like to admit and the grand fabrications of popular art have golden nuggets of pure truth hidden inside of them.

But, for all the ideas flowing through Dawson City, it is most intoxicating as a sonic and visual achievement. It is vibrantly intelligent and rich in ideas, but nothing compares to the powerful pull of its emotional current. It is rare to have a documentary that feels this lusciously, elementally sensory, and the overall sensation of seeing it is one that I cannot put into words. It’s the way Bill Morrison presents the facts, events, and personages of this sprawling story and lays them on top of a fascinating bed of film imagery, without any talking head explaining their significance or how they relate to one another. It’s the way the fictional and the factual work off of one another, sometimes in perfect harmony and sometimes in ambiguous tension. It’s the gentle, steady heartbeat of Alex Somers’ wondrously effective score. It’s the narrative motifs that emerge. Populations ebb and flow like the tides. Historical figures emerge, disappear, and then suddenly pop back up to make their mark on history. Some of the people we meet become icons and others are only vital within the smaller story of Dawson City. In a narrative where Charlie Chaplin, Fatty Arbuckle, and Jack London all make appearances, the most important player in this film is probably just a town bank manager, who thought to bury some old film canisters under an abandoned hockey rink and unwittingly ended up preserving a big piece of history. It’s the way all these stories swirl around each other like wisps of smoke. It’s the way the film binds itself to the elements. Images of people, both fictional and real, trekking through the high drifts of snow. It’s fire after fire, as we hear of the many warehouses full of films that have went up in flames over the years. We learn that Dawson itself burned down once a year for the first nine years of its existence. It’s the unflagging fire that has devoured so much fragile human history and, in the case of those 533 films, it’s the ice and earth that preserved a small piece of it. And what emerges from all this sound and imagery is an impressionistic painting of what History itself might look like. Smoldering and water-logged and crackly and slipping away into beautiful, melancholy, discordant entropy. Bill Morrison could have simply made a documentary about film preservation or the Yukon Gold Rush or America in the early 20th century or even baseball, but what he has made instead is a nonsummative masterwork of the non-fiction form. It is a documentary as much about sensing History as it is about learning it. In making a film about how History is too elusive to see with undiminished clarity and too massive to take in all at once, Morrison has also crafted the perfect frosted glass aesthetic for that thesis. What may have started out as a small story about unlikely film preservation in a tiny Yukon tourist town ends up becoming an ocean in a teacup. In peering through a small window in American history, Dawson City manages to become a movie about humanity’s entire vain, gorgeously doomed attempt to rage against the finiteness of things. It is a film about a specific pocket of time but the struggle at its heart is timeless.

That struggle is mainly the attempt to gain some clearer understanding about ourselves and the world we live in. That is something that we look to Art to help us do, whether it is a non-fiction book giving us greater clarity into a chapter of History or a great film helping us glimpse something fundamentally true in the human soul. And, to be clear, I do not believe Dawson City: Frozen Time is roundly dismissing the act of parsing our collective past or saying that it is entirely futile. Any film that renders History in such a thoughtful, visually rich way must have some deep affection for the value of learning about what came before us. But this documentary does remind us that every golden nugget of time is an elusive, multi-faceted thing. The idea is not that humanity can never have any understanding of where it has been or where it is going, but that we would do well to remember that knowledge is a dense, refracting crystal. The truth of things can shift tantalizingly based on what corner of it we hold up to the light. It is not that there is no Truth, but that the nature of Truth is so brilliantly confounding that the process of looking over it is essentially never finished. Film was literally born of an explosive, but Dawson City sees History, Memory, Literature, and Art as being similarly prone to turbulence. All of knowledge is an incendiary, unstable element. Meaning can shift dramatically based on how we look at things and also depending on who is doing the looking. If there is a lesson to be taken, I believe it is that we should welcome a multitude of perspectives and that we should never fool ourselves into thinking we are done learning. But beyond any lesson, I think Dawson City is just reminding us that this is the way things are. To be alive is to both know things and also have that knowledge continually challenged and disrupted. The best thing you can do is to find some beauty in being mystified. If you don’t find yourself frequently confused, bewildered and awestruck, you probably aren’t doing it right.