Among the many qualities of Steven Spielberg’s basically autobiographical masterpiece The Fabelmans, the most surprising (especially if you’ve only watched its misleadingly tony trailer) is its humor. The latest brilliant collaboration between Spielberg and god-tier playwright-turned-screenwriter Tony Kushner is more than just surprisingly ticklish and light on its feet. It is often legitimately funny, as if to deliberately blow the dust off the acclaimed veteran director’s prestigious reputation. One of the funniest things about it is that its conceit relies on a truckload of braggadocio from the populist master. The Fabelmans goes well past the point of a humble brag and veers into bragging full-stop. Its thesis calls for one iro-clad premise: Steven Spielberg is, and probably always has been since his birth, an utter genius at every single aspect of making films. It’s a boast that he is using to engage in some very pointed self-deprecation and self-criticism, which feels like a particularly trusty kind of Jewish humor. There is something dryly funny in someone laying all their faults and neuroses bare by very directly stating that they’re kind of inarguably a genius. The Fabelmans is Spielberg’s most personally confessional and painful film, an analysis of the inner darkness that fuels his art and how much his wondrous filmmaking is actually an outlet for trauma, guilt and unexorcised demons. The genius, he explains to us with a wry smile threatening to break across his face, is actually not entirely a good thing. It’s the byproduct of his masochistic drive to dredge up old pain and his own unresolved emotional issues. He’s telling us that there’s a can of icky worms behind every spell-binding, magical movie he’s ever assembled. A primal scream behind the wonder and technical wizardry. The Fabelmans is rich with honest-to-God jokes. And the best joke of all might be that the greatest popular director of his generation makes a movie about puncturing his own genius that also sends the audience out with another reminder of that same genius. The man has never been more nakedly revealing nor more warmly hilarious.

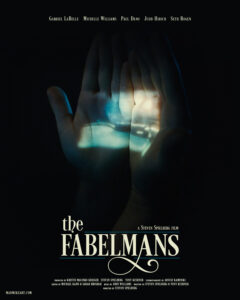

The Fabelmans picks up at a New Jersey movie palace in 1952, where a six-year old Sammy Fabelman (charmingly played by Mateo Zorya for the first quarter of the film and by an electrifyingly confident Gabrielle LaBelle for the remainder) is about to watch his first genuine motion picture. The feature presentation is Cecil B. De Mille’s polarizing, bloated extravaganza The Greatest Show On Earth (mainstay on the lower half of ranked Best Picture lists). His two very distinct parents, genius engineer Burt (a wonderfully sweet and sad Paul Dano) and spirited art lover Mitzi (a terrific and poignant Michelle Williams) are trying in their own ways to ease Sammy’s nerves about the spectacle to come. Burt is using science to rationalize away his little boy’s trepidation about watching 20-foot tall people on screen, hoping that explaining how movies work might make them less intimidating. Mitzi is gushing about the dream-like magiv of movies. It’s a classic set-up for a cliched “power of the movies” coming of age scene, but what plays out subverts that. This will not be Spielberg’s CInema Paradiso. The movie scene that burns itself into Sammy’s brain is not some feel-good slice of enchantment but a grandly violent train crash complete with screeching metal and one horrifying death. The Fabelmans will follow through on its premise as the autobiography of Steven Spielberg’s lifelong love affair with the movies, but the journey will be exceedingly more complicated than you can imagine, borne more out of fear, dysfunction and heartache than childlike whimsy and schmaltz. It is the story of Sammy’s life with his Jewish family,. which consists of his diametrically opposite parent, two younger sisters, and a surrogate uncle figure named Benny (Seth Rogen, relishing the chance to add a completely different kind of film to his resume) who works with his father and shows up to every holiday and vacation. It’s an observant, intimately scaled domestic drama (one Spielberg had wanted to make for many years) shot through with the kind of majesty, invention and dewy emotion that only our finest blockbuster director can provide. It winds from New Jersey through Arizona and ends in the place you would expect the story of young Steve Spielberg to wrap up: Hollywood. And yet, nothing about hos this lovely, empathetic story unfolds feels expected or cliched. It is one of the most delicate, natural and spontaneously alive of Spielberg’s career and it is also the kind of breathtakingly confident, engaging entertainment you make when you are at the height of your powers. Spielberg tells an insular little yarn about a hard thing he and his family went through when he was a kid and somehow brings down the house once more.

From its opening scene, Spielberg is trying to get at the nature of who he is as an artist and push back against the idea that he is only driven by wonder and childish innocence. He cagily locates himself at the nexus of vivid, often dreamlike imagination and precise whiz kid technique. He is a man of magic and science and The Fabelmans is his endlessly shrewd unpacking of how one sphere of his talent has always butted heads with and simultaneously relied upon the other. When a teenaged Sammy Ingeniously figures out how to create the illusion of gunfire in his first Western film by poking pinholes in the film that allow light to shine through, his dry father’s face lights up with childlike amazement. But, in the next scene, Burt asks his son why he isn’t devoting his prodigious talent for engineering to more practical, useful matters. Most engineers use their knowledge to design and invent practical things. Engines and bridges. Sammy’s inventions are cinematic dreams, cobbled together with economic proble-solving. His scientific discipline cannot be separated from the sense of magic he gets from his mother. The left and right brains of his two parents enrich each other and spar with each other. The Fabelmans is very much about the uneasy, if always loving, marriage of his diametrically opposed parents. But the core of his parents’ story is also the seed of Spielberg’s own cinematic identity. His films have always been a place where practical ingenuity and cinematic wonder coexist. , where one is impossible without the other (it’s what made him such an ideal mentor to Robert Zemeckis, another effects geek with romance in his soul). With his unique blend of practical know-how and starry-eyed enchantment, Spielberg is perhaps like the version of silent director Georges Melies that we see in Martin Scorsese’s Hugo: a crafty toymaker. Steven Spielberg may have become a great engineer like his father, but he clearly had a different notion of the word “useful”. Instead of applying his rigorous craftmanship to cars or computers, he saved it for the beautiful dreams so cherished by his mother. And in that way, if only that way, he managed to keep his two beloved influences in harmony and in conversation with one another.

There is a deeper truth to science and awe in this movie than just how it relates to Spielberg’s folks. The Fabelmans is the story of Steven Spielberg’s most painful childhood memory and it is about how all of his art, sometimes misunderstood as sentimental and saccharine, is suffused with the hurt and fear he felt as a child. Even at their most seemingly crowd-pleasing, Spielberg is saying his movies are an outlet for wrestling with what troubles him and frightens him. His first theater experience, sold to him as a wondrous extravaganza, also greatly disturbs him. He is unsettled by the cinema at the same time he is captivated and inspired by it. The Fabel mans is a reminder that Spielberg’s films are not mere wonder delivery systems; there is always some degree of horror mixed into the recipe. His world-beating Jaws, a film so fun that it literally invented the summer blockbuster, is also a bloody horror mov ie where an almost imperceptible menace lays waste to a small town’s Americana facade. ET, a sublimely magical piece of coming-of-age science fiction, also has one of the most viscerally upsetting death scenes; in any film, let alone a studio family blockbuster. His Hook, a film oft-malighted for its cheesy artifice, only takes us to Never Neverland after an unsparingly ominous kidnapping scene. In one of the setpieces from The Fabelmans‘ second half (an hour-plus cavalcade of perfect scenes that sent me out of the theater giddy), se see Sammy invent the fabled Spielberg Face, where an actor looks offscreen in a close-up that focuses on their awe-struck wonderment. Bu the source of the “wonder” in this scene is a carnage-strewn battlefield and the subtest if the crumbling of Sammy’s home life. The Fabelmans recontextualizes even the most plainly feel-good instance of Spielbergian wonder as an act of trying to shine a light into the gloom. The magic is real, but there is always some amount of pain and torment behind it. Spielberg has made a masterpiece about how the things that delight us and the things that terrify us are maybe one and the same. They are part of the great tapestry that Spielberg has spent his life mastering. One great and terrible quilt of enchantment and dread.

One poignant and funny truth that Spielberg arrives at is that what scares him most might be himself. After watching that brutally explosive train crash in his first trip to the movies, the initial fear gradually fades to reveal an even more alarming truth: he loves the fear. Exciting or unsettling, Sammy only knows that he is helplessly drawn to it. In The Fabelmans, cinema is not some magical, sweet fairy brightening Spielberg’s young life with uncomplicated mirth and pixie dust. Cinema is more like a Nosferatu, a vampire with murky intentions that takes little Sammy by surprise, bites him and mutates him forever. That first viewing of The Greatest Show On Earth didn’t just rattle young Spielberg. It imbued him with an insatiable hunger, a bottomless obsession. From the outside The Fabelmans may look like it’s going to be one more love letter to the movies, but it’s actually about a fearsome addiction to them. Of course, this being our maestro of wonder and spectacle, the film’s account of that debilitating addiction cannot help but be dynamic, compelling, moving and ticklishly funny. The great joke of the film is Spielberg trying to point to the darkness in himself and having sparks and confetti shoot out of his fingers. His incurable curse is the world’s gain. By the end, Spielberg seems to almost lose his own argument, as he and his audience are washed away in a tsunami of sharp humor, visual wizardry and richly humane vibes. Sammy’s elderly, prodigal uncle Boris (Judd Hirsch, doing more with ten minutes of screentime than should be humanly possible) warns him that art is no game. Once it has its hooks in you, if you are a true artist, you will be helpless prey to it. It will infest you and command you. It will fill your soul with poetry but it is a spout that cannot be turned off. We get plenty of romantic films about the siren song of art, but Spielberg may have made the only film of this kind to really contemplate how the artist can be dashed against the rocks of their own divine calling.

Spielberg’s effervescently great West Side Story cracked my top twenty films of 2021. In that review, I noted a couple Spielberg qualities that The Fabelmans also runs with. First is Spielberg’s most vital collaborator over the last two-plus decades: genius playwright Tony Kushner. John Williams is regularly and rightly discussed as maybe Spielberg’s top collaborator on the basis of decades of iconic, brilliant scores. But, since 2004, Spielberg and Kushner have had a four-film spotless miracle run together: Munich, Lincoln, West Side Story, and now The Fabelmans. It’s a partnership as fruitful as it is impossible to pigeon-holeThe eloquent mournfulness of Munich gave little sign as to how the two men would make the passing of the Emancipation Proclamation both lively and subtly humorous in Lincoln. And Lincoln is distinct in its greatness from what they would do to bring a well-worn 1950s musical into the 21st century with sharp topicality and vibrant immediacy. The common thread of their stunning collaborations is just a sparkling attentiveness and an irrepressible sense for how to make material dazzle and sing. The other compliment I paid Spielberg in my West Side Story review is his incredible eye for discovering up and coming talents. After directing a virtually unknown Ariana Debose to an Academy Awards two years ago and discovering new star Rachel Zegler, Spielberg has found a tremendously exciting young actor in Gabriel Labelle, his teeenaged avatar in the film. Labelle’s tapdance between fizzy comedy and wrenching drama is simply a stunner. Like the director who has raised his profile, he seems to have a grasp of the places where joy and tragedy exist together. The kind of dark rainbow of oil and water that Spielberg only gets better and better at blending together.