Great art has a way of making one think about other great art. In the case of French director Alice Diop’s transcendent courtroom masterpiece Saint Omer, an early moment made me reflect on cinematographer-turned-documentarian Kristen Johnson’s 2016 opus Cameraperson. There’s a gripping montage in that movie where Johnston briefly shows places where atrocities have happened: an old hotel where Bosniean refugees were tortured, a pickup truck that was used to carry out a brutal hate-crime. There is no talk; just background noise and informational titles to let us know what transpired there. What Johnson is doing, fittingly for a craftsperson who spends so much time thinking about where to shoot, is wrestling with the hypnotic power of space and place. Without saying a word, she is showing us how a mere building or room or site can take on a haunting reverie, as if some trace of the violence that took place there remains, like an eternal echo of the past. Diop’s cracklingly cerebral Saint Omer unfolds almost entirely in a French courtroom (in the northern French commune of Saint Omer) where a desperate young Senegalese woman has been accused of drowning her infant child in the nearby sea. Another black French woman, a novelist and college professor, has chosen to travel to watch the trial and possibly make it the subject of her next work. As the trial audience takes their seats, the regular players of any trial file in and we watch them go about their routines. Lawyers from each side shuffle their papers. Magistrates dutifully take their seats on the bench. A reporter takes photographs of the half-full courtroom before being sent out by the judge. And finally, a young black woman is led in handcuffs to the stand. What stood out to me was something uneasy and electric under the procedural banality. The camera was shifting and hovering about the room to take in the various people, swiveling back and forth to look around. But, to me, the gaze felt less interested in these bureaucrats than in the wood-paneled space of the court itself. I sensed it was taking in this space; a space of great power where countless lives had been ended or forevered altered. In a film about gazes and observation, Diop was first showing me how this unassuming room holds these people and how it will hold some trace of them after they leave. Just as it holds traces of the people who have come before them. As Diop unveils overlapping frames of perception over the course of two hypnotizing hours, the static, unconscious space where her story unfolds almost seems to have a point of view all its own.

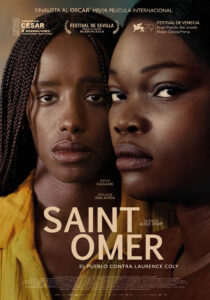

One of 2022’s primary virtues was a kind of fountain of youth quality, where everything old felt new again. Prestigey war epics had a touch of the subversive and personal (when they weren’t All Quiet On the Western Front), director autobiographies dodged cloying preciousness and bristled with potent honesty. Action cinema announced it could be anything it wanted to be. And, in the case of Saint Omer, we got a courtroom drama (that most reliably staid of genres) with a haunting ambience and an understatedly radical sense of cinematic bravado. Taking place in recent times and inspired by a real French infanticide trial, Saint Omer is about two French Senegalese women living in France. The first is Rama, a media professor and respected writer who travels to the seaside community of Saint Omer to view the subject of her next book: the trial of a woman who left her 15-month old baby to drown on a moonlit beach in Northern France. The second lead is the accused, an elegantly poised and regally tragic young Senegalese immigrant named Laurence who came to France to become a student and slowly lost touch with her family and the outside world as her circumstances, financial and social, worsened. At the time Laurrence killed her infant, (a flatly admitted fact in a movie about how few stone cold facts can be found in our world), she had been living in the flat of her callous boyfriend, a much older man with a wife and grown child, who kept her a secret from everyone he knew. He left her there alone for long stretches of time as he left town to attend to matters of his real life. He was surprised (appalled, the way Laurence puts it) to return to the flat one day and find Laurence in bed nursing an infant child; their infant child. Mental illness, the slow death of her professional dreams (she aspired to become an educated philosopher) and the total decay of her entire social support net all played some role in driving her to the terrible decision she is now standing trial for. There are no flashbacks whatsoever in Saint Omer. Instead, like our surrogate viewer Rama, we are made to bear witness to a staggering tragedy told almost entirely through the words of an adjudged, publicly demonized woman. The magic trick that turns a subdued French courtroom into a the scene of a drama rich enough for Sophocles requires only one doomed immigrant woman’s words and an audience to witness her speaking them.

Saint Omer is a film about paying attention to voices society has a habit of shutting out. Immigrants, people of color, women and specifically mothers. Like last year’s superb The Lost Daughter, Alice Diop’s stunner is a film about the complicated nature of motherhood. Both films choose to focus on people we could glibly write off as unfit mothers, but the struggles and maternal limits of these women are actually a testament and a show of empathy to anyone who has ever borne children. As Rama prepares to travel to the trial in Saint Omer, she attends a birthday luncheon for her own mother, a quiet, pained woman who does not utter a word to her successful daughter. We pick up traces of a fraught history between mother and daughter and we sense Rama’s mother struggles with a mental illness that kept her from being an ideal parent. We sense pages of painful history in her stoic, haunted expression. Rama clearly fears becoming her mother. We subtly glean that she is also about to have a child of her own. Her husband tries to assuage her anxieties. She is not doomed to retrace her mother’s steps. The woman who raised her is miserable and broken, where Rama is secure and loved. But that easy dismissal, however well-intentioned on her husband’s part, is the very kind of judgment Saint Omer resists. Rama has gone to the trial not just for research but as an attempt to understand. As Rama watches a forsaken mother bear her soul and contemplate the atrocity she has committed, she feels the life growing inside of her. And in that moment, the differences between this mother and that, this daughter and that, fall away. There is just Motherhood, a state that binds and connects countless women across space and time. We can make judgments and proclamations about unfit mothers and wronged children, but it feels too easy, especially for those who have not stood in that position. That judgment may be deserved, but Diop and her observing protagonist find no insight in it; no empathy or humanity. Judgment feels obligatory and inevitable, and also just a bit hollow and obvious. Saint Omer is not so much decrying that laying of blame as suspending it in amber. It’s setting it aside to examine more complex questions. Before we get to assignments of a guilt (a guilt the accused herself all but confesses to in the trial’s first minutes), is there a time to reflect and feel sympathy? Diop’s radically humane notion is that every mother, no matter how monstrous, is owed a scintilla of our empathy. We cannot hate them until we have at least heard them. If they must be judged, then we must witness them.

Coming out of law school, I wanted to be a Public Defender. Family members were concerned for me, unsure of why I’d put myself through such a grueling, low-paying emotional wringer just to defend the guilty. Leaving aside my belief in the rule of law and the fact that the innocent do get accused of crimes, I was moved by the idea that even those who have committed despicable acts are owed some kind of consideration. They are owed a moment of our attention before we lock them away for years or forever. It is not much but, before they are deprived of almost everything (and sometimes everything), I feel strongly they are owed a moment. A simple gesture of humanity; an attempt to hear them and understand them on some level. That notion is the thematic core of Saint Omer. It’s the reason the plain facts of this terrible infanticide are immediately laid bare and never disputed. The facts are not the point here. The question of guilt or innocence is purely decorative. The real question posed to the audience is, “Doesn’t every person deserve to have their story heard?” No matter what sin a human being commits, should they not at least be given what Rama describes to her grad students as “a moment of grace”? Saint Omer is a mesmerizing morality play where a guilty woman gets to briefly command the attention of a society that debased and degrade her when it bothered to regard her at all. It falls under the court procedural genre but its nature is profoundly spiritual. Its emotional tone is curious and probing. It cruises right pas the idea of factual innocence to contemplate deeper ideas of vice and virtue. It is about the soul and a kernel of worth and human dignity that not even the vilest murderer can have stripped away from them. It asks why we would want anyone to have these essential things stripped away from them. Saint Omer is so very much more than a courtroom drama. But also, in the way it grapples with the essential nature of criminality and redemption, it may just be the courtroom drama. It pulses under the surface with ideas about what justice is and what it should be. It grasps the value of seeking justice and it also knows how two-dimensional and unsatisfying that justice often is, even when it reaches the technically correct outcome. Asking if a person is guilty or innocent is just a fact of life, the way our world works. That said, it may be the least interesting question we can ask.

Film connoisseurs love to talk about lenses: perspectives that is, not camera glass. Whose lens are we seeing the film through? Who is telling this story? Can their perspective be trusted or they an unreliable narrator? Saint Omer is a film very interested in lenses of perception because it is a film about the nature of truth and seeing. It is a film about seeing things through the eyes of people who often go unseen themselves, in much the way that the accused Laurence talks of being tucked away from sight by her absent boyfriend. Saint Omer presents lens inside of other lenses and it is about the tricky matter of finding truth among so many subjective perspectives. While it is largely the story of a bright, misunderstood, tragically neglected young black immigrant, it is also about the brilliant black scholar watching her. Rama is the successful intellectual that Laurence so fervently aspired to be. In a way, Rama is taking a three-day hiatus from her role as professor to take what you could call a class. She is becoming the student of Laurence, a fellow black intellectual whose own dreams of academia have been cut short. And it is, of course, about a pregnant mother listening to the words of a failed mother, hoping to understand what it even is to be maternal. Rama sees a parallel to her own strained relationship with her mother in the gulf between the accused and the mother who never figured out how to be there for her. Rama’s gaze repeatedly moves over to the older black woman watching her daughter with weary, regretful eyes, and we momentarily remember there are even more lenses we could be observing this trial through. Saint Omer is a story about seeing and being seen. It is about wanting to be seen and going unseen. It is less about a specific crime than it is about the entire struggle to understand what is true. And it is richly about the hated defendant, Laurence, getting one last unexpected chance to display her unseen multitudes; her sharp insights and her philosophical depths. And, when all these lenses and conceptions of individualized truth are laid atop one another like transparencies at a lecture, you get a luminously devastating prayer to black womanhood and womankind as a whole. Saint Omer‘s refractions of female identity are so poignant, interesting and stubbornly unresolved, it deserves to be maybe the first cinematic text referenced when the subjects of feminism and intersectionality are discussed.

It’s actually difficult to sell myself on the idea that Saint Omer is only 2022’s eighth best film. I watch it and instantly recognize it as a titanic treatise on nothing less than knowledge itself. It feels like that annual masterpiece that is not only destined to rise in my rankings, but is rising at this very moment. If there are seven better films, I don’t know that any of them (not even the boldly cerebral TAR) is as self-evidently a work of genius, a thing of real challenging, scholarly beauty. It is abut the aspiration to beautify and sharpen our minds. As a means of bettering ourselves, as a means of lighting up our own worlds, even when they are impossibly dreary. While the crowds picketing outside the court see Laurence only as a loathsome monster, Rama sees an irrepressible life force. A monster, yes, but one with a striving mind and a complex heart. I think the entire top twenty of this phenomenal year is going to age like fine wine, but Saint Omer is one of the handful I can already guarantee will mature into a timeless classic. Because perception, morality, and the nature of truth and knowledge are as eternal now as they were in Hellenic Greece. This is the kind of film that is so hauntingly self-assured, so scintillating and sorrowful, I don’t believe its potency will dim. It’s a work of art destined for the Criterion Collection and the Sight and Sound poll. As I gush about it, I have the feeling this won’t be the last time I breathlessly try to wrap my mind around it. It’s humbling to watch a film that speaks so potently to its moment while already belonging to the ages.