For longer than I can remember a certain breed of comedian (we’ll just call them Gervaises) has loudly and performatively insisted that comedy is dying on the vine. “Comedy is over” has been the doomsday refrain of a whole host of thin-skinned and overwhelmingly male (give or take a Whitney Cummings) standup comics, beside themselves that audiences are no longer letting homophobia, transphobia and bigotry slide just because the person saying it is at a comedy club. It’s a hysterical bad faith response easily debunked by simply watching or listening to any of the numerous hilarious and empathetic comedic geniuses working today, from Patton Oswalt to Jenny Slate to Nathan Fielder. Proof that comedy is far from over exists right here in the fact that, for the first time in my years writing reviews, a comedy special has ranked as one of my ten best films of the year. Innovative, comedian-turned-exciting-new-director Bo Burnham’s (now two for two after 2018’s humane and deliciously awkward adolescent dramedy Eighth Grade) creatively restless and anxiously topical “special” is a visionary meditation on where this poor world stands, sent out from the lockdown prison of one 30-year old man’s cramped apartment. In one of Bo Burnham: Inside‘s first songs (oh yes, this is a musical comedy, a term that is ill-equipped to contain the sheer scope of what Burnham is up to), our quarantined funnyman host also asks the question: Is comedy over? He blessedly means it in a very different way than your typical disgruntled male rights activist. What Burnham is bemoaning is no the comic’s sacred right to offend without critique. He is asking the larger question posed by Andrei Tarkovsky’s bleak but life-affirming masterpiece Andrei Rublev. In times of extreme sorrow and strife, does art have any real power? Are literature and music and now comedy nice things that wither in the face of real disaster? As we look out our windows at the rise in ocean levels and in worldwide authoritarianism, is a comedian’s punchline or silly ditty really worth all that much? In that song, simply titled “Comedy”, Burnham asks, “Should I be joking at a time like this?”, as a canned studio audience laugh track plays behind him. He just as quickly puts his own selfish solipsism in the crosshairs by recommitting to “healing the world with comedy”. Like the rest of Inside, the song is musing on the limited power of art while also skewering the vain folly of thinking that our good intentions and kind sentiments can fix what is broken. “If you wake up in a house that’s filled with smoke, “Burnham softly croons over an 80’s synth tone, “Don’t panic. Call me and I’ll tell you a joke.”

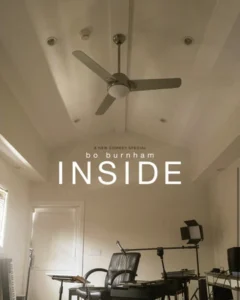

Limits are not just Burnham’s key themes (COVID’s limited spatial freedom, limited emotional energy, and a world whose days feel increasingly limited). Limits also provide the film with the great production challenge that makes the whole thing go, as Burnham tries to make use of a single room, a Casio keyboard, some rudimentary lightshow equipment, some microphones, and a camera to create a work of art that feels expansive and boundary-pushing for all its claustrophobia. It is the very fact that he is working with a sparse set of tools and no visible collaborators that makes his haunting, manic depressive message in a bottle feel so perversely fun and spontaneous. Inside is a relentlessly melancholy film and arguably the most downbeat piece of work to ever earn the classification of comedy special. But it is also very, very funny. Burnham knows what he is doing and the goal is to leave us in a heady, contemplative and disoriented headspace. Yet he also finds room for a gleefully silly song about FaceTiming with your folks, a Sesame Street parody with dystopian undertones, and a riotously scathing pump-up tribute song for Jeffrey Bezos, sung with barely contained rage. It may be too soon to identify a signature style that ties Inside together with Eighth Grade and Burnham’s past stage-based standup specials. But what stands out early in his directorial career is an unpretentious appetite for experimentation and an appreciation for cringe humor done in the right way. He has always had a Weird Al playfulness about him. His first instinct is to keep things light, goofy, and anarchic toward pop culture trends. What makes Inside so captivating and alive is Burnham’s willingness to let that more winking sensibility merge and mutate with a newfound sense of real darkness; the dread he has come to feel in these increasingly troubled few years. In taking a year-plus to document the effects of quarantining on his mental well-being, he makes the important choice to lean into that dread. To not worry if his anxiety and depression will overwhelm the comedy in what is nominally billed as a comedy special. He trusts that even all-consuming panic and mental disintegration can be funny, and he is absolutely right. He fully gives himself over to the demented experiment and ends up duetting with his own demons like a mad drunkard in some ramshackle piano bar.

If art does sometimes feel powerless to offset a mounting ledger of catastrophes, it is still one of the only positive byproducts of tragedy. The hope of anyone living through those much-feared interesting times is that the trauma and adversity will at least provide the inspiration for a handful of brilliant songs or films. The sweet pixie dust foxtrots from artists like Benny Goodman, which enchanted and soothed a generation grappling with devastating poverty and staring down the Nazis. The brilliant noir films cooked up in a climate of post-World War II paranoia. Th ecstatically beautiful, angry, and playful rock and roll that exploded form the powder keg of the 1960s. In that spirit, Bo Burnham has presented us with the first masterpiece to come directly from the monumental tragedy of COVID-19. Inside is not simply an examination of the mental toll of having to isolate to keep each other safe, though it speaks to that quite eloquently. It is also an audacious and formally brilliant visual essay of the COVID lockdown experience. The struggle to find something new to do after months and months in a single space. The oscillating between morose despair and bursts of manic, pent-up energy. The way so many stayed glued to the insanity and the reports of death because it at least provided some kind of emotional rush when everything else felt mired in the doldrums. Burnham uses tricks of light, projections on his walls, and a full-body shaggy camouflage suit to conjure up his own subjective experience of lockdown. Beyond the songs and their messages, Inside‘s stylistic creativity tells a story all by itself. The story of a person trying every last idea he can think of to occupy himself and distract his brain from the stark reality that he is stuck in a room watching the outside world get worse. In the end, as the physical world full of disease, mass shootings and mental illness gets more dangerous to exist in, we find ourselves sheltering indoors more and more. An as our real homes inevitably come to feel more claustrophobic and oppressively familiar, we all get funneled toward a world that shapeshifts and tantalizes us with the possibility of transcending our cramped physical reality. A world that makes us a Faustian offer of never-ending stimulation and pacification. The prophecy uttered by The Social Network‘s Sean Parker has come true. We are all living on the Internet.

Inside is a film rich with ideas about the ominous, disquieting, and fascinatingly absurd trappings of life in the current age of the Internet. The late capitalist Internet. The Trump Internet. The Internet with the power to launch righteous progressive movements and just as quickly funnel them via algorithm into echo chambers that dull their rhetorical power. As Burnham remarks in the devastating and intimate Father John Misty sendup, “That Funny Feeling, “In honor of the revolution, it’s half off at the Gap.” He laments a culture where corporations can leverage the name-checking of just causes into a rote dollar value. “Who are you, Bagel Bites?,” Burnham asks with tongue barely kept in cheek. Bo Burnham has long made a living off of pitch-perfect spoofs of post-2010 musical styles and social media trends. But Inside marks an evolution. Any sense of glibness for the thing being parodied has given way to something more grounded and less politically ambivalent. They say a great parody artist should have some love for whatever they are parodying and Inside finds Burnham clinging to some vestige of that love. A song like his Grammy-winning banger “All Eyes on Me” is just too heartfelt and genuinely cathartic not to have been made with real affection for the woozy, cerebral R&B that artists like Beyonce, Blood Orange, Frank Ocean, and James Blake made over the last decade. He loves the form and the sound of this music. And he has always used modern styles to his own Puckish ends; to playfully and knowingly rib at club culture and modern materialism. But the Bo Burnham of Inside has lost any trace of smirking archness. He’ll still give you a sparkly slow jam about the difficulty of deciphering emojis in “Sexting” or skewer social media tropes in “White Woman’s Instagram”. But he is unafraid to explore the serious harm of a digital culture that encourages constant saturation and precious little time for processing and unpacking. A platform that, as he sings on the towering standout centerpiece “Welcome To the Internet”, tempts us with “a little bit of everything all of the time.” Wearing demonic round shades, Burnham looks like the unsavory beatnik second coming of the apolitical master of ceremonies in Cabaret. Social media as the impartial, chaotically fun drug dealer to us all. Whether helping a disgruntled loner build a bomb or helping you learn which Power Ranger best represents you, the Internet takes all comers and refuses no requests.

Among his laundry list of anxieties, ranging from the global apocalypse down to lifelong panic attacks and agoraphobia, one major anxiety seems to be how our digital solipsism, that insatiable thirst for likes and followers, is cutting us off at the knees in terms of being able to do effectuate meaningful progress. Hobbling our power to do anything about the threats to freedom and continued terrestrial existence. Comedy obviously isn’t going to save the world, but what is going to save us if we are all lost in an opioid haze of narcissism and needy vanity? We have great public stages where we can shout many noble and eloquent words at each other, but Burnham mourns how the power of those words is becoming diluted. Inside‘s visual style is brilliant because it makes us feel more and more like prisoners of a demented, echoing funhouse. The features of the small space are regularly obscured and distorted by disco lights and lasers and skewed camera angles. Burnham projects clouds and sky onto the walls as a reminder of what we’re missing or maybe in a feeble attempt to make this space feel like the new outside. In the middle of a YouTube video advising people not to commit suicide, he smash-cuts to the now-filmed anti-suicide PSA playing across the screen of his own chest. He stares vacantly at the back of the room, uninterested in his own pious voice. The deeper I progressed into the vortex of Inside, the more I started to realize that this isn’t just an impressionistic, gonzo snapshot of COVID quarantining. It’s reckoning with a death of the soul and mind that may have begun a decade ago or more. He seems haunted by a need to figure out when everything went wrong. “You say the world is ending, honey, it already did,” Burnham’s auto-tuned voice croons. Does Burnham mean the start of the pandemic and its cataclysmic death count or does he mean the world ended at some earlier time that we somehow didn’t register? Inside was filmed in response to lockdown but its mournful subject is a kind of lockdown of the human spirit that predates March 2020. The maddening thesis of this hilariously devastating musical is that a cavalcade of pre-pandemic ills (gun violence, the eroding of empathy and community, Trumpism, the Internet-ification of our every word, thought, and social activity) conspired to trap us inside in a way that may be irrevocable. Locked inside of ourselves and our neuroses. Shuttered away in rooms within rooms within rooms within rooms.

Inside is a comedy special on Netflix. It’s occasionally haha-funny, but more often than not it’s hugging-your-knees-and-nervously-chuckling-to-yourself-in-a-corner-funny. To be fair, still funny. That still leaves it as one of 2021’s comedic treasures. Even if, as Burnham himself theorizes, “comedic” seems like a feeble word to encompass what it is going for. And if the price of good, rich laughter is hyperventilating a bit and questioning the very fabric of modern reality, I’m ready to call that sanity well spent. I’ve paid more of my mental stability for far lesser works of art. I paid theatre prices to see Tom Hooper’s Cats, for Macavity’s sake! And, with the right tour guide, a nice voyage into madness can be a vital and liberating experience. From the time I was old enough to drive myself to a movie theatre, I’ve been an ardent fan of animator Don Hertzfeldt, ever since I saw his Oscar-nominated short film Rejected at Berkeley’s sadly defunct Shattuck Cinemas. The singularly macabre auteur makes films that puncture social niceties, grapple with ennui and mental illness and dance along the nexus between what is real and imagined. Hertzfeldt has the sheer talent to make a schizophrenic man dreaming of an anthropomorphized talking fish feel both upsetting and uncomfortably uproarious. More than anything, Bo Burnham: Inside feels like the first time a live-action director has taken up Hertzfeldt’s mantle as a chronicler of terrifying, claustrophobic modern absurdity. The first film to bring that unsteady, humanely maniacal sensibility out of Hertzfeldt’s Shanty Toon Town and into the three-dimensional world. Like Don, Bo chuckles into the abyss. And when the abyss chuckles back, the sound is unmistakably that of canned laughter.