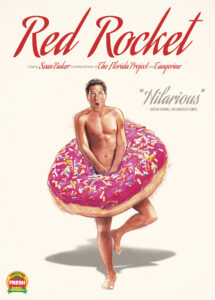

In 2017, Sean Baker made The Florida Project, my favorite film of that year. It would have been my favorite film of a great many years that it might have come out. In it, he directed genius screen actor Willem Dafoe to the best work of his career, gave us one of the best child performances of all time from Brooklynn Prince, and also got stellar work out of a young woman most famous for being an Instagram influencer. And, following up on the talent he showed with his iPhone-shot 2015 gem Tangerine, he created a luscious hardscrabble world populated with non-professional actors and got them all to give lovely, lived-in performances too. So when I saw that Baker’s next film, Red Rocket, would star former MTV VJ-turned-Scary-Movie-franchise player as a shifty porn star, I chuckled and shrugged my shoulders. Nothing about that premise sounded like the stuff masterpieces are made of and I have never once been impressed by Simon Rex. Nonetheless, I smiled to myself and said, “I guess I’ll be raving about Oscar-worthy Simon Rex a year from now.” It has now been more than a year since I made that half-joking prediction, and I am here to say that it has absolutely come true. Simon Baker has directed a retired C-list actor whose most recent brush with fame was as a comedy rapper named Dirt Nasty to what is arguably the best male performance of 2021. Because fucking of course he has. Because, just as a small part of myself made that prediction in jest, a much larger part of myself knows better than to bet against Sean Baker. But the wondrous thing about a Baker film is the potential it makes you see in everyone he works with too, whether it’s Willem Dafoe or someone with no acting on their resume. And here let me stop making this all about Sean Baker, because I am fully done disrespecting Simon Rex in this review or anywhere else in life. Baker may make miracles possible, but the work Simon Rex has pulled off here is a mighty dramatic and comedic accomplishment that should utterly recontextualize how people see him. It was unsurprisingly too much to hope for that the year’s best leading male performance sneak into an Actor lineup that had room for Javier Bardem in Being the Ricardos. But I can only hope that this does mean the start of new things for Simon Rex. If nothing else, watching him go for broke (even broker than the character he plays) in Baker’s gonzo neorealist satire of hustlers and hucksterism should show all of Hollywood that he has a potential that very few of us had been able to see.

And, for anyone venturing out into Baker’s small but luminously empathetic filmography for the first time, showing new sides and facets of disrespected and marginalized people is exactly what the inventive auteur is all about. Framed in a certain way, Baker’s story is another tale of an impoverished underdog trying to grind out some modicum of success and happiness for himself. Out of work adult film actor Mikey Sabre rolls broken, bruised and destitute into his tiny Texas hometown, the latest sad sack to be sent packing by the city of Los Angeles. Like former Baker protagonists (Tangerine‘s Sin-Dee, The Florida Project‘s Halley), Mikey is no stranger to bad decisions, but those other protagonists were also very easy to root for in all their hardscrabble tenacity. It’s less clear from almost the first minutes if MIkey will be deserving of that same empathy, a fact you might glean when his ex-wife greets her prodigal spouse with curse words and demands to remove himself from her property. To be clear, Mikey Sabre is a real piece of work. He is irresponsible, narcissistic, impulsive, and self-justifying. He might have “The check’s in the mail” tattooed on him somewhere. After worming his way back into the house of his ex-wife and mother-in-law with promises to help them with rent, he very quickly starts insinuating himself into the lives of former friends and colleagues. Whatever humility and pity we might have ascribed to him when he entered the picture broke and beat up quickly evaporate when we realize that Mikey will simply never stop trying to work the angles. No sooner has he seemed to get back in the good graces of his former spouse and established himself with a profitable drug-dealing gig, his eyes start drifting to bigger opportunities. When he meets a winsome and Lolita-esque cashier named Strawberry at a local donut shop, his eyes fill with cartoon dollar signs and the goal of a peaceful, harmonious homecoming ceases to be enough to satisfy him. His restless Mountain Dew imagination sets his sights on making Strawberry into the next adult film star, setting himself up as her manager, and rolling back into Los Angeles to lay waste to his naysayers. That is what he wants, but it is almost folly to ask what MIkey Sabre wants because Mikey Sabre is really just want personified. His wild-eyed, gonzo narcissism makes him the kind of person for whom the goalposts of success are forever being moved relative to how well he’s doing. And it is possible and not the least bit wrong to go through the entire film without finding him genuinely likable. But, for my part, I defy anyone to not find MIkey Sabre fascinating, compelling, and sometimes even improbably endearing.

After the luminous pathos of The Florida Project, Red Rocket is something of a return to the raucous and manic comedic sensibilities of Tangerine and my worry coming in would be that Baker’s faultless empathy would somehow finally fail him; that this decidedly white trash character would finally land him on the wrong side of condescension and mean-spiritedness. I don’t know why I ever had that worry. Sean Baker still fuses fully tactile working class (and unemployed) settings with a sense of ragged vivacity that can run the gamut from screwball to Felliniesque (he sure does love to capture interesting faces and body types). His worlds are populated with persons too unique and specific to fit into your average social drama. And he seems incapable of belittling or talking down to a single inhabitant of these tiny, hard-scrabble universes. It’s no small feat here because he introduces a protagonist in Mikey Sabre who is not afraid to show condescension himself. For all I’ve spoke of Simon Rex’s marvelous creation as an endearing underdog, there is also a fair bit of ugliness in the way he looks down at the small potatoes stomping grounds that birthed him; the place where he suddenly finds himself an economic prisoner. Even as Mikey slides back into the rhythms of downtrodden Texas life, he makes no secret of his feelings that he was made for much grander things. And yet, in spite of Mikey’s braying, sometimes downright mean bravado, Sean Baker loves him too up to a point. When Mikey shows some unexpected early flashes of grit and and work ethic, I think Baker is proud to see him not fall into some easy deadbeat archetype. There is more to Mikey than meets the eye, just as surely as there is less to Mikey than Mikey himself would have you believe. I think Baker is happy to once again give us a character who confounds our expectations for him and is not simply a victim of impoverishment. But it is also clear enough that Mikey is not the mpathetic lover of humanity that Sean Baker is, which makes him altogether different from even a frustrating Baker character like Florida Project‘s struggling single mother Halley. Mikey is undeniably toxic. He is a vampire in every emotional and metaphorical sense of the word. The journey of Red Rocket is how he improves his prospects and what schemes he hatches, but it is readily apparent that Mike Sabre’s relationship to other human beings will always be parasitic to some major extent. And his sympathetically vulnerable veneer quickly crumbles when he sees he can do better than simply move back in with his middle-aged wife. As soon as he meets the not-yet-18 Strawberry, his eyes are filled with dollar signs and money shots, and Baker makes no comment as to which desire of Mikey’s we should regard as more perverse. Red Rocket sees Sean Baker applying his sense of lush humanity to his least sympathetic character and the challenge he and Simon Rex set for themselves produces a work of art every bit as singular and intoxicating (albeit in a 4 Loko kind of way) as Baker’s last two, more outwardly empathetic films. I imagine Red ROcket‘‘s Mikey Sabre may shake off some viewers like a vulgar bucking bronco and I don’t think Baker judges anyone for despising Mikey at some point on this journey. But he he is also with MIkey, selfishness be damned, for the full two hours. And not as some sort of edgelord exercise in seeing how long we can put up with an unforgivable piece of shit. Baker sticks in Mikey’s corner because there are traits and ideas in Mikey worth the exploring. And because looking deeply into the souls of difficult, aggravating human beings is what Sean Baker was put on this Earth to do.

I think part of what allows Baker to thread the needle of both Mikey’s unsavory narcissistic avarice and his almost endearing smarm is that the vibrant auteur is unafraid to shift in a multitude of comedic registers. Sean Baker deploys offbeat humor in tremendously effective ways. If you remember those parts of The Florida Project that didn’t have you crying buckets full of tears, you might recall that it was also frequently hilarious. Baker has a sharp knack for when to make us laugh, whether it’s to help a sad insight go down a little easier or, in the case of Red Rocket, to help us spend time with a monstrously egomaniacal charlatan without wanting to climb out out our seats and our skins. And, with his unlikely high wattage leading man charging forward in a hail of sparks, Baker turns Mikey Sabre into a fascinatingly low-rent version of the kind of con man that American audiences have often taken a shine to. America is quick to forgive flim flam, usually because flim flam can be so much fun. Mikey lacks the easy charms of Paul Newman and Robert Redford in The Sting or even the more shambling underdog charisma of Christian Bale in American Hustle.

If the suavest con men act like magicians whose hands you never see move, we see every frantic gesture Mikey Sabre makes to advance his various seedy agendas. We see his ploys coming seemingly before he does. For as shifty as he certainly is, his cards are also kind of on the table if only because they keep falling out of his sleeves. If many a great huckster never lets you see them sweat, sweat is really the main and only export Mikey Sabre has to offer. He is a poorer, sadder, meaner con man for poorer, sadder meaner times and there is much more venomous critique in his story than in breezy concoctions like The Sting and the Oceans films. And yet, as pathetic as Mikey is, Baker and Simon Rex just make him an awful lot of fun to watch. What he finally has in common with cinema’s other great, and infinitely more talented con men is that he cannot help but put on a show. Less a suave light show of a man than an erratic bottle rocket that will inevitably set some poor sucker’s lawn on fire (if not multiple suckers), he nonetheless makes for fiendishly captivating viewing. And without wanting to reduce Baker’s lively American satire to pat lessons, one takeaway from Mikey may be that our country has become too undiscerning about the kinds of flim flam men we let bewilder us. Once the hangover of Mikey Sabre wears off, the moral may be that America deserves to go back to a better class of ripoff artist.

Still, Baker does not judge his characters for sometimes letting a two-bit hustler like Mikey walk over them. He understands too well how so many people like them are looking for something nice to hold onto and believe in even if that something rolls into town with nothing but bruises, a ribbed tank top and a suitcase full of red flags. Even in this decidedly acidic skewering of the American Dream (or its porn-based equivalent), Baker finds beauty in blight and commercial sprawl and industrial drabness. He finds something bold and stirring in what people do to give themselves a little bit of hope each day, whether it’s a trip down to the megamall or an afternoon watching court TV shows. He finds love and humor in the people who inhabit these spaces and he loves to pick out splashes of luminous color, wherever he can find it. He loves gaudy hues, but he sees nothing tacky in them. They are, if anything, a shout of defiance in the face of real soul-killing ugliness. It’s this approach that made The Florida Project‘s fleabag motel into its own violet-hued Magic Kingdom, and it makes Red Rocket‘s tale of small town claustrophobia and stalled dreams feel strangely transcendent. It is a film grounded in the real and with an eye toward escape. You can feel how the yellow glow of a donut shop and its frosted wares might feel like a rare and welcome sprinkle of joy ane release for someone like Mikey’s unemployed wife or the numerous refinery workers who start their mornings there. As the stars in Mikey’s eyes become ever larger with the wild prospect that Strawberry will help him make his Hollywood (read: San Fernando Valley) comeback, Baker adds more bright hues via a visit to an amusement park and the loud Madonna Inn pink paint job of Strawberry’s house. Pink. “It’s supposed to make you happy or something,” Strawberry wryly muses. I believe Baker is giving us the first overt thesis statement of his filmography, a purpose behind all the delicate pastels and thrift store Technicolor that make his films so deliciously saturated. Though I don’t think that the nature of all that bright color is as obvious as instant happiness. I don’t think Baker’s sunny color schemes are a clean antidote to the hard living inside his worlds. I don’t think Strawberry or any of the other denizens of this Texas bardo believe that either. At the same time, I also don’t think the lovely hues are meant to be dismissed as superficial or cynical in some Tim Burton kind of way, as if they were only masking hopelessness under a thin sheen. Like art, like any pleasing thing, I think the color in Baker’s universes does what it can for his characters. I think they all take the little snippets of beauty and fun in their sometimes dispiriting lives for every bit of solace it is worth. Which is to say, both a great deal and not nearly enough. The color is supposed to make you happy, which means you try to seek happiness in whatever patch of cracked pavement it lives in. And that attitude towards life is all the more important when so much around you is gloomy and broken down.

And when you allow hard-hit characters like these to have a little hope and humor and defiance, to laugh and fight on through their troubles, you stave off rote miserablism. You can sidestep the kind of voyeuristic piteousness and punishing bleakness that is the natural hazard of the neorealist genre. It does not mean that sorrow is not sometimes a part of Sean Baker’s films, because they can absolutely knock the wind out of you when they have a mind to. But it feels humane to be with the characters, by their sides instead of watching them with concern from a clinical distance. What allows Red Rocket to work is that the people, mostly women, that Mikey Sabre tries to manipulate or placate or exploit are largely on to him. Sean Baker has created some wild and puzzling characters in his young career, but he really doesn’t do rubes. The women Mikey tries to steer toward his seedy ends do allow him to sakte by with a great deal of sexism and chicanery, but Baker’s characters are always real people with complex inner lives. It is Mikey’s failing not to recognize that. To only hear his own conceited, cocksure, motor-mouthed voice as it drowns out everything else. To pay mind to nobody but himself, narrating his great story in a never-ending stream. To never once consider that he might not be the smartest man in the room or in this small town or in the state of Texas. So the women let this delusional charlatan boast and carry on. Maybe it’s because they are good-hearted enough that they are trying to figure out, just as we are, if Mikey is deserving of love or sympathy or an honest break. Beyond better angels, maybe they also have their own uses for Mikey. Strawberry flabbergasts him when she reveals (in a brilliantly staged scene at the top of a rollercoaster) that she knows all about the porn star past that he was so craftily concealing. The cagey daughter and second-in-command to the matronly pot dealer who begrudgingly employs Mikey sees right through his cheesy patter and Eddie Haskell bullshit from the moment they meet. She lets him make money for her family, but she is also sizing this Svengali up, deciding when it will be time to cut him off at the knees. And MIkey may worm his way back into Lexi’s bed, but he gives her too little credit too. Mikey’s parallels with Donald Trump eventually mean that Baker is willing to give him a little nuance but is unwilling to let him off the hook or let his callous narcissism go unexamined. Yes, Red Rocket tells us, we Americans can be too quick to let a certain kind of self-serving parasite use and demean us. But the cinema of Sean Baker is always full of empathy and love and faith in the essential goodness of people, even if those people can sometimes make disastrously bad decisions. The residents of Sean Baker’s films are strong and fiercely intelligent and determined to survive. The effervescently generous director reminds us that the megalomania of greedy and ethicless men must surely fall in time to the patience, solidarity, and resilience of smart, resourceful women.