I keep coming back to 2019 as the year of the director’s diary. I’m beginning to feel like a human echo, but, in a year with this many confessionals and personal ruminations and memoirs, it frankly bears repeating. While a number of auteurs meditated on what makes them tick, maybe no one examined themselves as directly as the iconic queer Pope of Spanish Cinema, Pedro Almodovar. Almodovar was arguably the most important artistic and cultural figure to emerge from Spain’s La Movida (Spanish for “the Movement”), the tidal wave of bold expression, feminism, open sexuality, and boisterous hedonism that broke loose after the death of Francisco Franco and his decades-long fascist regime in 1975. To see a typical Almodovar film (though there is hardly anything typical about them) is to take in an intoxicating blend of subtle camp, juicy melodrama, and multi-hued humanity. They are born of a love for ripe telenovelas and for social justice. Like Tarantino, Almodovar was forged in movie theaters (according to his Pain and Glory surrogate, his childhood screenings were shown outside on building walls and smelled of pee, jasmine and summer breezes), where a young, impoverished and closeted seminary student could take in the subtle subversion of Luis Bunuel and maybe dream of a time when subversive filmmakers no longer had to cagily sneak their social statements past dead-eyed censors and their despotic overlords. The sum of Almodovar’s influences (his sexuality, his upbringing as a Catholic, the enthusiastic veneration he has for women and motherly figures in particular) can all be detected across his films, like notes of fruit in a bottle of Rioja, with certain of them more pronounced from work to work. I don’t know that there’s really a wrong place to start with the compassionate,frisky, vivaciously sensitive open book that is Pedro Almodovar, but the autobiographical Pain and Glory is an absolutely marvelous primer on the man’s journey through the decades, while marinating in that mixture of flamboyance and self-doubt that makes him a truly special fixture in Cinema’s Hall of Legends.

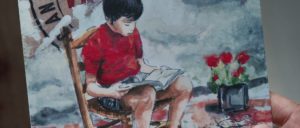

Pain and Glory covers much of the span of Pedro Almodovar’s life, thought it is largely focused on a recent time during which the now elder director was weathering a slew of relational, medical, and existential maladies. They included the death of his beloved mother, a sudden heroin addiction brought about by years of chronic pain, chronic pain, a possible tumor in his throat, and a long spell of director’s block owing to the aforementioned misfortunes. Like Almodovar’s own rendition of Fellini’s 8 1/2, this is the story of an artist in crisis, presently unable to do what he was born to do, and trying to reason (and in this case opiate) his way back to creative normalcy. Pain and Glory is what we call a memory play, gathering anecdotes and impressions from different times in the protagonist’s life and assembling them into a kind of dreamy quilt of reminiscence. Our Almodovar surrogate is named Salvador Mallo (brilliantly played by Almodovar’s old muse, Antonio Banderas), a celebrated Spanish director who has not produced a new work in some years. In flashback, we meet young Salvador, a poor child from a rural family, whose father moves them into the only place they can afford: an underground cave. A beautiful, white-walled cave, with multiple rooms, a view of the azure sky and filled with piercing Spanish sunlight, but a cave nonetheless. To help his mother (very well-played by Penelope Cruz, another longtime Almodovar muse) make ends meet, he gives reading and writing lessons to a handsome, iliiterate young housepainter. That man will eventually give Salvador his first inklinks of attraction to his own sex. In the present, the chronically depleted Salvador learns that one of his earliest films from the 1980s has been elevated to classic status, and that a film society wants him to host an after-screening Q & A with Alberto Crespo, the lead actor he fell out with many years ago, due to a creative disagreement over this very same film. An unexpected and at first uneasy reconciliation between the director and his former muse (in real life, the actor is believed to have been Antonio Banderas himself, lending a wonderful bit of metatext to Banderas’ portrayal of Almodovar) brings new opportunities and complications. Alberto ends up introducing Salvador to heroin as a way to manage his pain, which also makes it impossible for Salvador to muster up the energy to work again. At the same time, Alberto finds an unpublished short story on Salvador’s desktop and requests the rights to turn it into a one-man show, as a kind of olive branch between them. This very personal short story going public gives us a glimpse into Salvador’s 1980s heyday (the same decade when Almodovar inspired the gay community and marched his country defiantly and flamboyantly away from the repression of its past three decades). It also brings the gift of a painful ghost whom Salvador has not seen in decades.

Pain and Glory is a lovely film that begins with a director closed in on himself, fearful he will never create again, and unable to make peace with the tormented past. Then, he has lunch with an old actress friend and she brings up the subject of his film retrospective and the old friend and creative partner Salvador thought he could never see again. But he has nothing else going at the time and the proposed symposium must feature both of them, and so he feels his hand is forced. He musts reopen an old, scorched history and broker some kind of truce with the man. And, from that decision to apologize and forgive old debts, Pain and Glory unspools into a lavish, cascading melody of regret, remembrance and human connections. What’s perhaps most crucial isn’t just that Salvador needs to reconnect with Alberto. It’s that he realizes he was at least partly to blame. Their fight had been over the quality of Alberto’s performance, which Salvador had long felt went against the nature of the character he conceived on the page. Now Salvador realizes he was wrong about how he saw his own art. Pain and Glory is a wise and generous film about realizing the folly of our stubbornness. Of shaking our head in embarrassed wonder at how cocksure and unbelievably certain the previous versions of ourselves appear to our present selves. It’s the beauty of allowing the real man Almodovar fell out with to play him and share in the Almodovar’s confession of fallibility. And the same mixture of wounded pride and humility plays out in the scenes with Salvador’s mother (who loved him fiercely and tenderly, even while her devout Christianity made it impossible to be open with her about who he was), and the former lover who sees the production of Salvador’s story and instantly knows it is about their time together. The fond, warm, and tearful scene where they reunite and reminisce over tequila is so poignant and gracious, I would gladly watch an entire Before Sunset-style film just about their one evening together. In Almodovar’s generous, understanding hands, forgiveness just feels so overwhelming and vital and well-humored. Now more than maybe ever, his honest, unabashedly melodramatic voice feels so very much like the elixir we all could do with more of.

When it’s not conjuring a small tropical storm of bittersweat tears to run down your face (and when it is, as often as not), Pain and Glory luxuriates in a rich, understated kind of humor. It’s not explicitly out to draw chuckles, but its love and intuitive grasp of its characters is so astoundingly full, you quickly feel you know and love these people. And when you know and love a character, then you understand what drives them and frustrates them. And that’s when a kind of empathetic, knowing laughter comes easily, the same way it would with a friend whose motives and foibles you understand almost innately. One way the film accomplishes that is by being a thoroughly relatable portrait of writer’s block, or any kind of doldrums. As of this time, late April of 2019, I’m sure a lot of people can empathize (and hopefully laugh a bit) with the idea of being mopey, bored, and stuck in one place. Antonio Banderas is playing a rundown and jaded version of Pedro Almodovar, which means he is playing a rundown and jaded version of one of the least historically jaded artists I can name. If Pedro Almodovar has blue moods, I have to think they aren’t technically blue; maybe more like a slightly desaturated rainbow. He can be quite serious, maybe even glum or dark in a splashy way, but his moroseness still crackles with an unquenchable impishness that even a full-blown health crisis (I mean the one in the film) can’t tamp down entirely. Such is the delicious vivacity, heart and wit of Pedro Almodovar that even an autobiography of his chronic illness and malaise somehow tickles you. With an artist like this, there’s just no taking the spark out of them. And, my God, the way Anotnio Banderas uses his simmering charisma to suggest the irrepressible Almodovar flame fighting to blow the lid off of his pain and grief is one of 2019’s true delights. An undervalued indie actor who became a smoldering matinee idol in the States reunites and makes peace with the man who discovered him all those decades ago, plays that same man in a film about their complicated artistic dynamic, and earns his first Oscar nomination for the best damned performance of his career and possibly the whole year. Two kindred homegrown Spanish talents shake off the dust and show they can still breathe passionate, contagiously joyful fire. How can it not make one smile?

From kitschy soap-evoking early work like What Have I Done To Deserve This? to the horny Hitchcockery of Law of Desire to turn of the century masterworks like Talk To Her and All About My Mother, there’s always a jolt of sweet, human, and invariably horny electricity with Pedro Almodovar. This is the man who spent his formative years under one of the worst fascist regimes in history, and then lived to tell about it and triumphantly urinate all over it in big block letters. No wonder even Pedro Almodovar delving into insecurity and personal pain still vibrates with so much color, humor and eroticism. Once you’ve escaped a system that demanded you straitjacket your very identity, why would you ever stop running, dancing, fucking? I’ll reiterate. In times that are drawing us ever closer back toward fascism, how many voices you can name are more vitally necessary than the likes of big-hearted, Technicolor, unapologetically queer Pedro Almodovar? His approach is anti-fascism by example. It is anti-misogynist and anti-homophobic in the same way. Exist freely and wear your empathy on colorful, puffy sleeves. Present a motley gallery of diverse characters. Housewives, prostitutes, soap opera stars, and priests. Women (if anyone can name a more vocal and eloquent ally for transgender personhood, in all of moviedom, I’d be surprised), men and the very young. In Almodovar’s youth, a genius like Luis Bunuel had to sneak around and smuggle his messages in forms that soulless Francoists would be too dirt stupid to detect. That was what made him genius. Almodovar was gifted to come into his voice at the exact time the barbed wire fell; when the rigid, cruel shites went away. So why not explore and emote and march and indulge? The fascist lifeguards were gone and he could sprint around the pool to his heart’s content. If we’re to have to deal with this pathetic and vile sort of person again, I’m glad we have Pedro to give us a blueprint for telling the repressive and hateful to kindly fuck themselves. Live loudly, joyfully and truthfully, and hope you naughty incandescence becomes contagious.

What you find across Almodovar’s work is a desire to be grateful for the things that made you, in a way that still has teeth. He has a boundless zeal for humanity, but his view of them is not facile either. One clear example is Almodovar’s experience with the Christian Church, which gave him an education he could not have otherwise afforded and helped him develop his own talents further. It was also a system that forced him to hide his sexuality. The tense interplay of rebellion and tempered gratitude for religion is a huge theme in his work. The same is true of the mother he both adored, yet also had to hide his true self from. Pedro Almodovar is clearly a man who loves human beings, while also understanding how thorny and painful relationships can be. But he always leads with the desire to see people as people, even when they are myopic and hurtful. And he, more than any other filmmaker I can name, adores the women of this world, in all their many shades. In a film full of flashbacks to tender, formative memories, the first one we get feels particularly loaded with affection and meaning. As the older Salvador floats below the surface of a swimming pool (part of rehabilitation for one of his critical surgeries), the water around him sends his mind floating back to an early memory of water. He is a very young boy and he sits by a lolling river. A group of women, his mother among them, wash laundry by its banks. They converse, they laugh, and they sing to each other. The scene is observed by the young Salvador, but it is not really about him. It is about him seeing (and remembering) the specific lives and inner light of others who touched him; these women who cared for him and sustained him. As we forge a widespread dialogue about respecting and demarginalizing women, I feel grateful for the director who has filled his gleeful, luscious frames with bold, smart, funny, and fierce ladies from the very start.