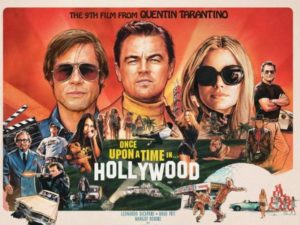

As I’ve said before, 2019 saw a number of great directors reflecting on their careers, some quite directly (Pedro Almovodovar’s Pain and Glory, practically the story of its own making) and some more obliquely (Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman). These films were an opportunity for some revered auteurs to revisit their pet themes and, in some cases, to author retrospective mission statements about themselves. Quentin Tarantino was forged in a slick 1970s theatre featuring kung fu and B movies, but he also had a childhood before that. As a very young child in the 1960s, his formative years would likely have been spent in front of a boxy Zenith television set watching juicy genre serials like Gunsmoke and Hogan’s Heroes. 2019 may have culminated with a certain directing legend voicing his distaste for comic book movies, but, funnily enough, this was the year when quite a few directing titans gave us their own personal origin stories. Agnes Varda took us on a gently probing and characteristically whimsical tour of her films. Pedro Almodovar gave us a lovely glimpse of the warm bath of openhearted queer sexuality and Catholicism that birthed him. And Quentin Tarantino, a director who has never shied away from wearing his lurid, grimy influences on his sleeve, got downright personal about the decade when he was born with Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood. I’m frankly in the camp that feels Tarantino’s films have a lot more honest emotion than they often get credited with, but this is really a horse of a different color for the foul-mouthed enfant terible. It’s a nakedly emotional, achingly fond dream memoir of 1960s Hollywood as it both existed and did not exist. A kaleidoscopic halcyon rendering of Swinging Sixties Los Angeles and a sincere thank you letter from a man who was touched and forever molded by its ambiance and iconography.

Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood is the third film in what you might call Quentin Tarantino’s Revisionist History period, along with Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained. It’s another film that is at least partly about an infamous real-life act of violence, where Tarantino uses his film to imagine a different outcome and a kind of justice for those victimized. The injustice he takes aim at this time is the 1969 Manson Family Tate-LaBianca massacre, which claimed the lives of eight people, including actress Sharon Tate and her unborn child. Thankfully, truly thankfully, Once Upon A Time is not the so-called Charles Manson movie that some may have feared it would be when it was first announced. That is to say that it is not a wallow in the horror of that tragedy, nor is it largely a revenge fantasy directed at Charles Manson. In fact the psychotic cult leader himself appears onscreen for only a span of seconds, very early in the film. More than anything else, the film is the story of two fictitious original characters, macho movie star Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio, as great as he’s ever been and now 2-for-2 with Tarantino roles) and his stuntman and personal assistant, Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt, immensely fun and making megawatt movie star charm look effortless as only he can). Mostly centered around a few days in 60’s Hollywood, it’s the story of two men from the old guard of 1950s and early 1960s entertainment staring down at the waning days of their careers. Once a lead in Westerns, war films, and a Gunsmoke-evoking weekly serial called Bounty Law, Rick shows up to meet with an older producer (Al Pacino, bouncing back nicely after all these years away) at the famous showbiz watering hole, Musso and Frank’s, and receives some bitter truth. His leading man days are done (he’s been increasingly handed small bad guy part where younger stars routinely defeat him) and his last chance to grab a little glory and enough money to comfortably retire on is to relocate to Italy and take some easy paychecks by starring in cheap Italian Westerns. Rick has some time to swallow his pride and consider the offer while he shoots yet another villain part on Lancer (an actual popular Western serial of the era). We spend time with Rick and also learn about Cliff, who has seen his stuntman work dry up after a scandal involving his wife’s demise and some less than professional antics on set. He now lives off Rick’s largesse, though he earns his keep doing housework, chauffeuring Rick, and being a true blue friend and sounding board. The other interesting detail is that Rick’s mansion happens to be on Cielo Drive, in the Hollywood Hills, next door to the home of Roman Polanski and his pregnant wife, Sharon Tate, portrayed enigmatically and almost elliptically in a gracious and touching performance by Margot Robbie. Tate would meet her tragic end at the hands of Manson’s followers in the 1969 massacre. Over the course of a day, Rick shoots what could be his last ever television role, Cliff pays an unplanned visit to the Spahn Western movie ranch where the Manson family squatted, and Sharon Tate runs an errand and makes an impromptu visit to a theater showing one of her first (of sadly very few) major movies. Before we come to the night of the killings, some six months later, we spend most of the film luxuriating in one sunny day in a lost Los Angeles.

The Hollywood of Tarantino’s deeply personal opus is Hollywood as it was and never was, a lavish patchwork of memories and celluloid dreams. For a film marketed right off the bat as a historical fiction piece centered around the Manson murders, Once Upon A Time is unexpectedly a very sweet movie. It is a thing born of deep affection for the whole filmmaking process; for stuntmen and starlets, those ascending and those on their way out and angling for the fabled comeback.Tarantino seems to be in love with the mystery of what makes a star, as evident in his canny casting of golden god Brad Pitt as a humble man behind the scenes. In this universe, a laconic, charming and endlessly charismatic guy like Cliff Booth is barely hanging onto a job. Without this or that circumstance, and that curious variable we call the It Factor, who knows where Brad Pitt himself might be today? On the other hand, a performer who might not look like much can surprise you. We first hear Rick Dalton rehearsing his cameo lines on a pool float, deep into a blender of whiskey sours, struggling to find something to sink his teeth into in his generic baddie dialogue. What we get when the film finally reaches Rick Dalton’s moment of truth on set is something altogether different than what we first hear. Once Upon A Time is partly a salute to the nonsummativity of art; to the almost unexplainable genius of taking the raw components of a production and somehow turning them into something transcendent. Of how a boozy, washed up old relic can flip a switch when he hears “Action!” and find a way to, as the professionals say, pop on camera. Rick needs to have his one last moment of brilliance, even if it’s just in this bit role, and watching him painstakingly work it out is one of the most thrilling moments 2019 put on screen. You may not think you have much in front of you, but great artists are resourceful. The true magic of making movies may be the canny art of simply making it work. Muscling through a low budget or an inexperienced cast or a hammy screenplay and spinning the flax into gold.

It’s the kind of alchemy that Tarantino has made a specialty, though he would absolutely blanche at anyone calling his scruffy, B-movie influences (kung fu, exploitation, grindhouse) cinematic flax. To him, those sleazy and violent films and TV shows had gold inside them all along. It may be more fitting to say that Tarantino’s skill lies in mining the rich opulence from genres that are often looked down upon. He has a fondness, a respect, and a fierce protectiveness for genres and people who are flatly dismissed. Think of how Pulp Fiction dusted off a scuffed up John Travolta and reminded the world of his talent. Notably, none of the major players in the film are your Marlon Brandos or Audrey Hepburns. The very famous (Steve McQueen, Bruce Lee, Mama Cass Elliott) are glimpsed only briefly. Our people are a fading star who exclusively made testosterone-fueled genre work about cowboys and war heroes, a comedic ingenue who died long before she ever reached her apex, and that most beat up and slept on of show business professionals, the stuntman. Tarantino loves an underdog, be it a star or a style. Part of what makes Rick Dalton’s unexpected triumph in his small role such a powerful moment is that he manages to find something Shakespearean in just a couple scenes as a vulgar, moustache-twirling heavy. Lancer is your basic unpretentious Western serial (you’d probably catch it on TNT or USA Network if it came out today), but the scenes Rick Dalton shoots with Timothy Olyphant (very good playing real-life Lancer star, James Stacy) are wonderful and fun and juicy and full of conviction. The point being made here by Tarantino is that the idea of high art and low art is utter hogwash. Art is art, and if you can watch Leonardo DiCaprio’s powerhouse work in the Lancer scenes of this movie and not see the beauty and power of it, your definition of what counts as art is probably too rigid. Let great work surprise you wherever you happen to find it! I love Lawrence of Arabia and La Dolce Vita as much as the next cinephile, but the 1960s gave us insight and sharp satire in less obviously high-minded packages too. From Planet of the Apes to George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead to Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch. These are smart, trenchant masterworks that stand tall to this day, but none of them ever competed for major awards or were held in nearly the same esteem as the prestige players of their day. Tarantino’s love letter goes out to an entire departed age of cinema, but, in characteristic fashion, he is an especially passionate champion of anything or anyone deemed lesser. If you ask him, there’s probably an episode of Bonanza out there with a guest performance so great, he’d take it over a thousand Hamlets.

In the film’s most touching and sweetly sad scene, Sharon Tate goes to pick up a book and spots a theatre across the street playing The Wrecking Crew, a Dean Martin spy comedy featuring one of Tate’s first supporting roles. It was also one that allowed her to stretch and show her gifts as a comedic actor. On a whim, she walks over and gets a ticket to see herself up on a big screen with an unwitting audience laughing and reacting around her. It is such a breathtakingly tender moment, joyful with the giddy delight of hearing an audience that likes you and hopeful for what this nimble talent’s future might hold. What it might have held if not for the unspeakable. Once Upon A Time does culminate in some brutal violence, but vengeance and carnage are not foremost on its mind. It is chiefly a director reminiscing on the decade of film and television that birthed him and pining soulfully for what could have been. There is a feeling of paradise lost to the film in keeping with other works about the death of 60’s ideals, like Fear and Loathing In Las Vegas and the Maysles Brothers Altamont documentary Gimme Shelter. The movies are a wonderful and pure thing, even the sleazy, bloody and exploitive ones, because they represent pure expression. Those sickening acts of barbarism in August of 1969 should never have been allowed to touch this creative fairy tale world and Tarantino will not let them taint it here. Of course, as you might expect, Tarantino retcons the Manson family in bloody fashion, just as he previously did for slavemasters and the Third Reich. But this revenge plays differently, feels different. The lingering impact is less about righteous satisfaction. Instead, what lingers is the wish for a world where the Manson clan is an historical footnote. Where nobody short of the most dedicated 1960s historian even knows Charles Manson’s name, and people sometimes get dressed to the nines to go see the latest Sharon Tate film retrospective.

Once Upon A Time is an extraordinarily lively and dynamic movie, filled with an enormous and talented ensemble (hello again Dakota Fanning, getting her own juicy comeback role). The film is eye-popping, quotable, stylish fun. But the paradox at the film’s heart is that it is also steeped in tremendous melancholy, wistful and lonesome and resigned to the unstoppable passage of time Sometimes, when Cliff Booth is driving his 1966 Cadillac DeVille around this bygone Polaroid of Los Angeles, old songs and snippets of radio jingles for old products will burble into the soundscape, and in those moments Once Upon A Time feels like a ghost story; one populated by enchanting, benevolent ghosts. Once Upon A Time may operate like a time machine, tinkering playfully with Hollywood’s past and correcting the calamities that hastened the era’s decline. But the film also knows that it cannot go back. Its very title signals to us that this is a fantasy, a dreamy, prismatic refraction of something beautiful and intoxicating and gone forever. With not a hint of irony or archness, Tarantino unburdens himself and offers an outpouring of sorrow and unguarded affection. For Sharon Tate. For a decade and all its lost style and music and glorious kitsch. I feel he succeeds in flying colors. Los Angeles has rarely looked so beautiful on film. Tarantino is justly celebrated for his pen, but my very favorite moment of Once Upon A Time may be a wordless one. As dusk starts to fall over the city, the neon lights of old theatres and cocktail lounges and Mexican restaurants start to flicker on one by one. Most of these places are now gone, like the people who frequented them, but Tarantino lets us see them again in their own lush, multi-hued light show. The old Hollywood haunts and all their beautiful, bewitching clientele still sparkle back to life in Quentin Tarantino’s dreams.