The tiny cinema snob in my head is screaming his little lungs off at me, but I need to do something that might not be critically kosher. I need to make some apologies and accommodations for my #16 film of the year. Attorneys, such as myself, have something called a severability clause. It means that, when some isolated part of a contract is just plain unworkable, that doesn’t doom the entire contract. Instead, like Groucho and Chico Marx in A Night At the Opera (the finest depiction of contract interpreting in all of cinema) you just rip that disagreeable section right out and carry on with the remainder as good as new. It’s cutting the moldy piece off of the cheese; a process that, with due respect to Ms. Sheryl Crow, should not be attempted with bread. It’s also damn shoddy film criticism. But let’s get back to the cheese. You see, unlike that loaf of bread, where the visible spores are probably just the tip of the fungal iceberg, you can take the odd expired bit off of cheese without fear that the rot runs all the way to the core. I would say that the clumsy handling of racism and police brutality in Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri falls into the category of bread mold because it has a way of contaminating even the film’s better parts. The Post, on the other hand, suffers from cheese mold. It’s a nice, block of fine, flavorful farmhouse cheddar with one corner starting to get pretty discolored and tough and another corner that is unmistakably starting to sprout fur the color of John Goodman’s character in Monsters, Inc. That first, less than appetizing corner is the film’s rote, uninspired opening. The Post is the story of the journalistic fight to print the Pentagon Papers, which exposed a years-long ploy by the highest levels of American government to misrepresent the odds of success in the Vietnam War and to foolishly continue along a sorrowful, bloody broken path even when Robert McNamara and other architects of the conflict knew victory was not possible. The Vietnam War is the context and the unseen backdrop of this story, which leads director Steven Spielberg to make an understandable but detrimental decision: to start his film with one of the most uninspired, apathetic depictions of the Vietnam War I have seen. The whole setpiece only lasts about two minutes. Spielberg handles it all as if two executive producers, worried that maybe some future viewer from some later generation won’t know what a Vietnam War was, are standing over his shoulder with a checklist of easy Vietnam War signifiers. And so Steven Spielberg, director of the greatest single battle sequence in modern cinematic history, tells us, with all the conviction of a child being forced to add a transition sentence to his term paper at 11:00 P.M., that the Vietnam War was, well, basically a war. It took place in a jungle and some men smeared black makeup under their eyes and everyone listened to Credence Clearwater Revival. He shows that fighting in the jungle was dark and muddy and there were explosions. The screen is dark and dim but not in a way that shows the murky, confusion of guerilla warfare. It just looks like slapdash cinematography. And then we’re off with Pentagon Papers leaker Daniel Ellsburg on a government jet back home, and Spielberg breathes an audible sigh of exasperation and relief. He is now free to tell the story he really wants to tell and the bracing sense of engagement that comes rushing into the film is palpable.

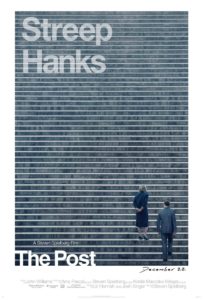

To be clear, I do not mean to trivialize what the Vietnam War means to this story or how much the loss of life in Vietnam present in the shocked betrayal and righteous urgency of the people fighting to ensure this story was printed. But, frankly, the nitty gritty details of what the Vietnam War looked like are tangential to this First Amendment struggle. One does not need to be reminded, by the 100th Vietnam War film in existence, that the War involved fighting in the dark and listening to 1960s rock music in order to know that a lot of young men died tragically over there and that a government hiding that it was all in vain is a pretty evil thing to do. The Post is really the story of how the Pentagon Papers were leaked, how the New York Times sought to print them and were quashed by the Nixon administration, and how the then-fledgling Washington Post, led by famed editor Ben Bradlee (a very big but rousingly fun Tom Hanks), picked up the loose ball and ran it the rest of the way to score a touchdown for press freedom. And it is about the twists and turns of that historic war of rhetoric and resolve and the groundbreaking Supreme Court case it led to. And it is about a whole lot of engaging characters, played with energy and moxie by talented character actors, bringing life to what it was like to stand in the merry maelstrom of a newsroom during that climactic showdown. Oh, and to stop burying the lede, it is about how much the fateful decision to thwart Richard Nixon and publish those vital, brutal facts came down to the Washington Post’s owner, Kay Graham (played with gorgeous intuition by Meryl Streep in my full-stop favorite Meryl Streep performance since 2002’s Adaptation). For, while The Post is a lovely, spirited film about the importance of journalism, it is quite a brilliant film about sexism, specifically in the 1960s, and in the present day by extension. In spite of being heir to the Washington Post, Kay’s late father left the paper to Kay’s late husband. Kay reluctantly stepped into the role of owner three years prior, when she lost her husband to suicide. Kay is a smart woman with a beaming sense of pride and affection for her news company, but she also carries a visible aura of self-doubt, which the strictly male business world she occupies is all too quick to reinforce. Even Kay’s closer allies, like her friend and business manager Fritz (the great Tracy Letts), seem to quietly believe that this kindly, insecure woman is here by accident and may not be well-suited to running a company. Adding to the sexist concerns over Kay’s competence is the fact that the Washington Post is about to go public, meaning any seismic activity, such as being sued by the President of the United States, could give the banks grounds to withdraw their investment. Journalist Daniel Ellsberg’s decision to disclose the Pentagon Papers to the Washington Post creates a perfect blizzard, both for the journalists trying to break the story an especially for Kay Graham, who is wrestling with doing the right thing for her paper, her readers, and herself, while also just trying to hear her own voice above the roar of even the most well-meaning male egos. It is a mixture of two narratives that matter a great deal to our current times: the freedom of the press and women’s rights.

With due respect to this watershed moment in First Amendment history, I am very pleased with how Steven Spielberg threads it with Kay’s story. Because, while the story of how the Washington Post defended the right to print is too vital to overstate, I would have hated for that urgent piece of history to become just another handsomely civic-minded issues film. And, for all that I love Tom Hanks growling and waxing about the holy mantle of newspersons, that is exactly what The Post could have been if it had only been an account of Journalism versus Nixon. If it achieved nothing else, having a great non-journalist character like Kay Graham there adds nuance to the usual notes of journalistic grit, simply by bringing in a different perspective. Her presence allows the film to breathe, if only by giving Hanks a complex foil; a dedicated, sympathetic woman who gradually awakens to her own understanding of how important her company’s work is, even if she will never be the ink-spitting, idealistic, occasionally sermonistic avatar of journalistic derring-do that Ben Bradlee is. I will not pretend that The Post is not a high-minded prestige film in some regard, but its journalistic grandstanding is leavened by welcome notes of subtlety and rich color. Among other qualities, it has one of the finer depictions of the tension between the ego of a renegade artist and the quieter, more grounded intelligence of a producer. Leaving aside how essential Kay’s status as a 1960s woman is to her character arc, she also brings the perspective of the person trying to keep the business solvent, which allows The Post to implicitly touch on the issue of news as both a public service and an industry, without that ever being its primary thrust. I could watch a film just about the weekly breakfast meetings between Kay Graham and Ben Bradlee. One could create an intriguing and insightful character piece just out of observing their fond but prickly dynamic and seeing them quibble and commingle about their industry. None of this lovely detail changes the fact that The Post behaves like a very stately message picture; the kind to which I am normally a bit resistant. But it becomes something much better than its exterior trappings because there is a sense of a world beyond this one legal fight. It is buoyed along by a broadly scintillating style of writing. It is also helped by a strong sense of character. Kay Graham stands as one ofthe most interesting, poignant people to appear on screen all year.

If I call Meryl Streep the MVP of The Post, including Steven Spielberg, I do think that is partially by design. I think Steven Spielberg knows Kay Graham’s arc is the secret engine of the film, hiding there almost in plain sight, much like Kay herself. I think he sees the genuine power in watching Kay gradually, firmly make herself heard, until her journey becomes the emotional thrust behind everything. The decision to publish under threat of Government retaliation was monumental, but it achieves a truly overwhelming power because the key decision comes down to a capable, underestimated woman who never thought she would ever be in that position. Part of that is just the truth of the story; it really was Kay’s decision. But, in tending to the two narrative fires, the story of Bradlee and his team and the story of Kay and her business, Steven Spielberg shrewdly knows that it is all building toward Kay’s fateful choice to not just publish but to disregard the misogynistic male chorus that attempted to drown her out. It can similarly be no accident that this very talky, sometimes visually subdued film hits its cinematic highs whenever it just empathizes with Kay. Watching her walk into an important Board meeting, Spielberg smartly portrays the Board room as an uncomfortably crowded space; a minefield of power ties. Later, as Kay tries to brush off a misogynistic slight on her competence by thanking her insulter, we see her boxed into the frame by two suit-clad backs. These omnipresent male bodies are a physical impediment to be navigated. Consciously or unconsciously, they push her toward the background of her own scene. Streep really is giving her most beautifully realized, ungimmicky acting in over a decade. She is The Post’s shining star but there is also a sense of an engaged inspired Steven Spielberg whenever she is around. The feeling of commitment and purpose he shows during her scenes stands in stark contrast to that drab, pedestrian opening. He has nothing new to say about soldiers fighting on a foreign shore, but unspooling the thread of Kay’s slowly dawning self-confidence makes his eyes light up.

More than anything, what makes The Post the rare case of a social issue film with vitality is how canny it is about creating a hybrid tale of journalism and feminism. The two weave around each other in ways that feel organic and fresh. Maybe the idea is to say something not only about the value of printing stories but about recognizing stories; about how storytellers should think outside of their own narrow worldviews. Ben Bradlee is so fixated on his own hero’s journey and the blow his team is striking against state oppression that it scarcely occurs to him to see Kay’s story. Until his wife opens his eyes to Kay’s position, he appears myopic to the personal stake Kay has as the Post’s owner and to how her status as a woman in business subjects her to a daily volley of pandering misogyny. It does not occur to him to see the story that Spielberg now has the presence of mind to see; that Kay and countless women like her brave a culture that casually, pervasively disrespects their intelligence and their capabilities. He does not see how, in their first scene together, when he snaps that she should keep her finger out of his eye, he is lending his normally noble voice to the malignant chorus that rings in Kay’s ears. He is, for that moment, acting as the antagonist in someone else’s story, and a journalist should be aware of that. The Post deftly dodges the traps of a typical journalism film due to its awareness that there are other battles being fought outside of the one to publish the Pentagon Papers. It becomes an uncommon sort of salute to female solidarity, because Kay Graham is a most atypical flag-bearer. She never sets out to carry any standard or lead any great fight. She is not a crusader. She is a kind, mild-mannered person who cherishes her home life and her children and planning parties. And recognizing that the struggle for women’s rights includes soft-spoken traditionalists like Kay is another way in which this outwardly stately period piece becomes quietly bold. Steven Spielberg may have set out to make a film that was quick and timely. In the wake of the 2016 Presidential election, he felt a need to champion the press’ right to publish and the danger of allowing authority to curtail that right. He gave himself nine months, which is a very short time to secure a script, cast the roles, shoot the picture, and complete post-production. And all that, combined with how prestigious it all sounded on paper, led me to expect something more valuable than actually good. God bless all involved that, in spite of those constraints, everyone involved had the patience and rigor to craft something better than valuable or good. The Post is humane, alive, and fully awake.

Of course, we then reach that albatross of an ending. I do not know if the tight schedule is to blame or if this is another case of Steven Spielberg’s perennial struggle with sticking the landing. I know that I already feel comfortable saying that it may be his worst ending and that it is certainly the most laughable when compared with the high quality of the material that precedes it. It could be that same old issue rearing its head. Or perhaps Steven Spielberg simply got tripped up by his own sense or urgency. Perhaps, in viewing Nixon as the unspeakable, mostly unseen villain of his piece, and in remembering that he was trying to hurl a brick at the new heir to Nixonian thuggishness, Spielberg couldn’t stop himself from getting histrionic. What I mean Is sometimes, when we argue passionately against something that incenses us, we can lose some of our focus to all that emotion and righteous anger. Suffice it to say, I think Spielberg tries to twist the knife hard into Richard Nixon, and I believe he twists the knife so hard that it flies right out of his hand, where it embeds itself in his otherwise terrific film. Without saying much more, this last scene gives one the sense that the Washington Post is about to get a visit from an eye-patch clad Samuel L. Jackson, and that Richard Nixon is going to spend his waning years hording plutonium in his Sky Dungeon instead of golfing in sad exile. It is all so tonally out of step with everything else, including that lackluster beginning, that I really have no qualms about chopping it right off. The Post is a great, imperfect film to cap off an imperfect year, but I am very glad to have it. This funny-looking block of cheddar gave me nourishment when so much of the cultural cupboard was bare. And, even in times of abundance, good cheese should never be taken for granted.