We hear the sound of Jackie before we ever see Jackie Kennedy. Before the famously forlorn First Lady’s face appears, the woozy opening notes of 2016’s best score envelop and disorient us. The buzzy, droning strings of Mica Levi’s menacingly pretty, beautifully tense composition sound out over a black screen before one sees a single frame of Chilean director Pablo Larrain’s visually distinct film. I think this is an important decision. Jackie’s music may be the best possible representative for what a paradoxically familiar and discombobulating piece of work it is. And “discombobulating” is about as fine a compliment as I can come up with for a film in a genre that, year to year, can be trusted to produce its fair share of lazy, formulaic films: the biopic. Jackie is a great biographical film for its keen insights into history, the way legacies are authored by the people who lived them, and what the lens of fame can do to something as universally human as death and loss. But, before it is about any of those things, Jackie is really about the subversion of the very idea of a traditional biopic and that first anxious exhalation of its score is basically the sounding shot to let us know this will be the case. The DNA of a stirring prestige biography is buried somewhere inside of Jackie, just as the sentimental strings and dignified horns of a standard stuffy biopic’s score are also there, struggling to make themselves heard over the more alien sounds. But the traditional polish of prestige has been scrubbed off, like some unvarnished piece of silver, to reveal all the rust and tiny cracks and strange protrusions that would have been tastefully sanded off of a standard biopic. Those first eerie notes announce a historical film that will be uncommonly honest as a picture of genuine human beings. However, Jackie also resists the idea that any biography can be entirely free of fiction. Mica Levi’s sinister strings and droning horns are partly symbolic of a biopic with more authentic warts, but they also call to mind a dense, confusing fog. They set the tone for a film that looks piercingly and unflinchingly at Jackie Kennedy and the days surrounding the Kennedy assassination but that also shrugs off the idea that its own idiosyncrasy makes it any less manufactured and fictitious than any other cinematic biography. Minutes after witnessing her husband’s death, Jackie Kennedy takes a hard look at her teary, blood-smeared face in an Air Force One mirror and then blurs her own image away with a swipe of her hand. And this is more or less how Pablo Larrain seems to see history in general; as something forever shifting in and out of focus.

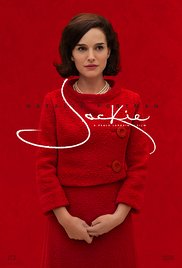

Jackie is the story of Jackie Kennedy in the week or so following the Kennedy assassination, but that story is set adrift in a dreamy haze of memories. The FIrst Lady is played as a dynamic, oscillating whirlwind of anguished vulnerability and self-aware poise by Natalie Portman. Jackie Kennedy is the best work of Natalie Portman’s career, and, if Jackie didn’t already give me so much to talk about, I could easily make this review entirely about her performance. While Jackie Kennedy tells her story to a reporter from Life magazine (Billy Crudup), we go back in time to the immediate aftermath of the Kennedy assassination and sometimes back to the more distant past, to when the First Lady would put on grand concerts in the White House ballroom or to when she gave a televised tour of the Presidential home that she had taken great pains to decorate with important historical pieces. The film presents Jackie as someone who believed in the value of great legacies and beautiful cultural artifacts, even as her husband dismissed it as a waste of money. The story at the center of Jackie‘s foggy reverie is Jackie Kennedy’s desire to give her husband the best state funeral that money can buy, both as a sign of love for him and as a means of ensuring that he is remembered by his country. On the night of the assassination, as she and Bobby Kennedy are being driven away from the hospital where John has just passed away, Jackie asks the driver what he knows of past Presidents. She asks if he remembers anything of James Garfield, William McKinley, and Abraham Lincoln. Even though all three were assassinated, Lincoln is the only one whose legacy he can really recall. Jackie recalls that Lincoln was mourned with perhaps the most elaborate, ornate funeral in American political history and she sets about to seeing that her husband is memorialized with just as grand a gesture. The true essence of watching Jackie is less about its basic plot than it is about bathing in its intoxicatingly sorrowful ambience and listening to its heady, rhetorical digressions. Cursing the fact that his brother got to do very little with his time as President outside of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Bobby Kennedy (played very well by Peter Sarsgaard) says that “history is harsh”, and this is something that Jackie, for all her love of history, also sees. Pablo Larrain’s film is about Jackie Kennedy having her own private war with the fickle beast that is History. It is her fight to ensure that her family’s legacy does not become lost to time and she shrewdly sees the funeral as a crucial battleground.

If Mica Levi’s undulating uneasy musical blend of reverent grandeur and dizzy discord is a good representative of the film as a whole, Jackie’s other technical elements also do an excellent job of tapping into the film’s themes of history as something too slippery to be entirely pinned down. Stephane Fontaine’s cinematography is beautiful and grand and showy and it has its share of shots that would not look out of place in the kind predictably lavish prestige picture that is Jackie’s disreputable kin. But somehow, once again, something elusive and unnerving is at play inside the familiar form. I am struggling to put into words why a white monument, bathed in fog, on top of a hill behind John F. Kennedy’s final resting place at Arlington feels different; not just haunting but almost haunted. In any ordinary film, the shot would still have a kind of gorgeous solemnity, which is also partly the point here, but there is also a kind of restless, bristling energy to the way Jackie uses a shot like this. As Jackie makes her firm, final determination of where her husband should be buried, there is an undercurrent of anxiety. My most current, and not at all certain, take is that we may be feeling Jackie Kennedy’s own mixture of dread and awe at the very idea of people having final resting places; the notion that living, breathing human beings stop living and breathing and then become finished stories, on gravestones and in memories. In ways I cannot entirely explain, Jackie is one of the only biopics I can name that feels a bit like a ghost story. The acting also bears out this tension between real people and what remains of human beings when nothing remains but their legacy. All the characters feel like flesh and blood, and yet there is also something mysterious and unknowable to them and this adds to Jackie’s ghostly tone. Lyndon B. Johnson is seen as a prideful, domineering figure, already too wrapped up in tending to his own public image as President to pay much mind to the devastated widow of his predecessor. In real life, Lyndon B. Johnson was a man who had at least some better angels, but the film does not let us past his imperious surface, and in any other movie, this would be a tremendous failing. As a matter of fact, this kind of presentation of Lyndon B. Johnson was a failing in Ava Duvernay’s otherwise very good Martin Luther King biopic, Selma. But Jackie is a strange and special beast and Pablo Larrain is a skilled enough auteur to use a kind of intentional opaqueness to the benefit of his film. This cryptic inscrutability feels of a piece in Jackie, where it might ordinarily feel like a piece was missing. This is not thin characterization but characterization that toys with our expectations and critiques the very idea that we can entirely know who Lyndon B. Johnson or Bobby Kennedy or Jackie Kennedy really were. Jackie is awash in a kind of fog that wafts around its subjects and keeps us squinting to see them just a little bit clearer. Pablo Larrain wants us to finally know, in his movie and in every biopic to come, that this kind of clear understanding is a vain effort.

Still, the last thing Jackie wants to do is discourage our curiosity about history. Larrain simply wants his audience to know that grasping history requires us to know that our vision can never be perfect. Making sense of the past means we must create a kind of helpful fiction. As Billy Crudup’s journalist (based off of Life writer Theodore H. White but given no official name in the film’s credits) is sitting down to conduct his interview, he tells Jackie Kennedy that he is striving to get to the truth but that he would settle for a story that sounds convincing. Jackie wants us to take this same approach in our efforts to make sense of recorded events. Jackie believes very much in the value of history but it would likely argue that the word “non-fiction” is effectively meaningless. The film is a fascinating, rigorous take on the idea of how human beings shape history after it happens, and what makes that stance all the more sharp and cohesive is how Larrain presents all this as a seamless extension of Jackie Kennedy’s own soul. For as much as Jackie is about looking at important people, including Jackie herself, through a sheet of frosted glass, one facet of the former First Lady is made very clear: Jackie Kennedy loved history. She cherished it and valued it and she thought very hard about how she and her husband would be remembered by coming generations. And so the film’s notion that sculpting a historical legacy is something of an act in creative writing is what truly illuminates Jackie Kennedy, even as that same approach is what makes her somewhat unknowable. It presents Jackie Kennedy as both the perfect subject and the ideal lecturer on the principle that history is a kind of ever-fluctuating mirage.

The question that I come back to the most with Jackie is what all this talk about mythmaking and historical license has to do with grief. Because, while the film philosophizes and muses over the nature of history, it also happens to be a superb portrait of bereavement. Jackie is one of the truest films in recent memory about what grieving feels like, and this is where it’s also important to remember what a narrowly focused period piece it is. Jackie is not the full story of the early 1960s or the Kennedys or even the three short years between the time of President Kennedy’s inauguration and assassination. It is really the historical account of Jackie Kennedy’s grief. Leaving aside the later Life magazine interview that is just there to act as a framing device, Jackie is focused on the short period of about a week in which Jackie had to deal with her husband’s death, move herself and her young children out of the White House, and tend to her husband’s funeral arrangements. It is really the story of how Jackie Kennedy went about throwing one of the most opulent and iconic state funerals in modern history and how she maneuvered around the many people who tried to silence her, from in-laws who wanted their slain brother buried on a private family plot to political handlers who didn’t want to run the risk of parading American leaders through the streets in the weeks after an assassination. It is the story of Jackie Kennedy’s long week of the soul. So I will pose the question that lingers with me every time I watch the film: what do grief and history have to do with each other? And I think the answer may be, “Not much. Usually.” That is to say, not much unless you are the widow of the most powerful, famous man in the world. And if you are, then, for one thing, your grief might belong to history whether you would wish it to or not. And what makes Jackie Kennedy the most electrifying, enigmatic character in Natalie Portman’s career is how it suggests the paradox of a woman trying to deal privately with her own sorrow while also realizing that grieving publicly may be the very best strategic card she has to play. In the throes of intense suffering, Jackie Kennedy came to understand that thrusting her grief even further into the national spotlight would do a world of good: for her husband’s legacy, for a shell-shocked American populace, and finally for herself. Pablo Larrain argues that a former First Lady who many saw as demure and airy showed a rather brilliant understanding of the optics of her own tragedy. A great many people wanted to close that ugly chapter before the ink was dry, thinking that it would be best for the nation to just move on. Instead, Jackie Kennedy wrested that chapter from the hands of powerful men, picked up a quill, and scrawled her name there in bold block letters. And in the end, it’s not just that our most iconic First Lady made a cagey move to cement her and her husband’s legacy. It’s that leaning into that grief rather than suppressing it turned out to be just what a frightened country needed to assuage its own anguish. And that, to the best of my understanding, is what grief and history have to do with each other.

I have sometimes heard Jackie described as a “cold” film and I can understand why in a way. It follows a traumatized widow in the aftermath of a terrible killing and watches her pain with an unsparing curiosity. It is also filled with soliloquies that would feel right at home in a collection of historical essays. It is a film with the academic rigor of a philosophy lecture and the deathly hush of a mausoleum, and I can absolutely accept that it is a cold film if you mean its mood makes you want to hug a loved one or at least put on a sweater. But I object to the idea that Jackie is, in any way, a detached or clinical film. Whatever one thinks of Pablo Larrain’s spectral, unorthodox period piece, I think they would be hard-pressed to deny that Jackie is a potent emotional experience. It is a film where history itself is less about a strict set of facts than the sheer feeling of a moment in history. What it felt like for America and what it must have felt like for Jackie Kennedy. If I asked someone what it was like to live through those weeks, I would expect that the overall mood of sadness and shock is what would stand out most in their memory. Grief and loss are like that, whether one is burying a parent or a President. As it’s happening, I imagine you do your best to fumble your way through the fog. Then, years later, when someone asks you what it was like, you sit down and do your best to write a story that feels true.