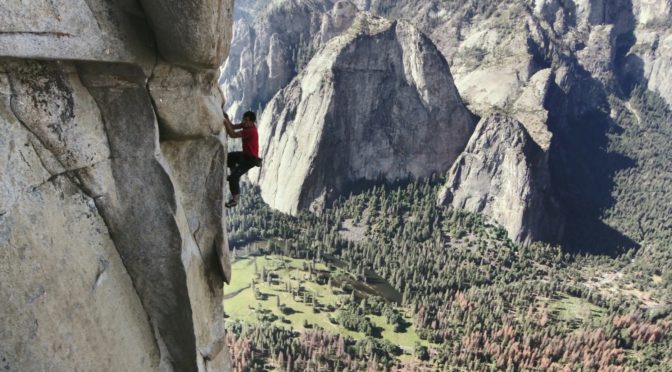

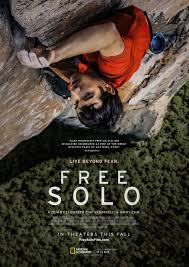

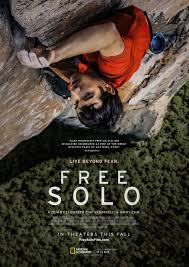

There’s plenty of complex insight and reflection going on under the surface of Free Solo, Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin’s recently Academy Award-winning documentary about free solo climber Alex Honnold and his mad quest to become the only person to ever climb Yosemite’s El Capitan without the aid of a rope. There are complex and thorny implications in his decision to willingly pursue a goal this life-threatening, the ethics of filming such a feat, and the psychology that might draw someone down this path. I know all that, reflective and absurdly somber would-be philosopher that I am. There’s also a bouncy, grinning ten year-old inside of me who just wants to be delighted, awed, and gobsmacked by amazing things. I told the child he couldn’t write this review lest he type it all in capitalized letters and make every fifth word “cool” followed by six exclamation points. Still, that was definitely the side of me that emerged into the light after each of my two theatrical viewings of Free Solo, beaming like a mischievous hyena and filled with uncontainable glee. I’m grateful that National Geographic (producers of the film) didn’t post merchandise tables outside of screenings. My inner child almost certainly would have dragged me over to them and made me buy him a hat or something. It’s his favorite film of the year (my fiance’s too) and it’s easy to see why. You see, Free Solo was quite simply the best time that I had in a movie theater in all of 2018. Both times. An unforgettable 90 minutes of laughter, seat-gripping tension, and audible, elated gasps. I couldn’t even recall the last time I sat with an entire audience so completely, collectively moved by and engaged with the film in front of them. Probably The Last Jedi. And if the level of palpable audience enthusiasm for a low-budget documentary about a niche area of climbing produced by a travel channel is on par with the enthusiasm for a world-beating, culturally inescapable mega-blockbuster, that speaks volumes to its crowd-pleasing power. It may sound like cliché, but Free Solo is that kind of film that reminds us why we go out to movie theaters. If it ever comes back into theaters (it ran for an astonishing five months at my local theater, quite impressive for a small-scale documentary about mountaineering), I urge everyone to watch it this way. Not just to take in the staggering enormity of El Capitan, but to remember what it feels like to gasp in unison with fifty strangers. My inner child, that perpetually caffeinated little moppet, was completely on the money about Free Solo. What I had just witnessed and been part of was ridiculously cool. My deep love for the entire idea of cinema felt beyond replenished. My filmic heart had expanded Grinch-like to three times its old size.

In truth, Free Solo is not just a pure, giddy document of beautiful athletic perfection. To free solo climb, to scale sheer mountain faces without any safety measures, should give us some measure of sober pause. It’s hard not to look at Alex Honnold and think of other men with unquenchable, quixotic thirsts for the ruggedly daring, and who eventually met sorry ends pursuing their passions. Names like Timothy Treadwell (whose death by grizzly bear was the subject of Werner Herzog’s masterful Grizzly Man) and Christopher Johnson McCandless (whose death by starvation in the Alaskan wilds was the subject of the novel and film Into the Wild) naturally spring to mind. Anyone who sees Free Solo comes away from it inevitably wowed by Alex Honnold’s unbelievable accomplishment and by his otherworldly composure as a sportsman. However, not everyone I’ve spoken to shared my unconditionally effusive elation about it. Some spoke, heads shaking back and forth, with a kind of soft, wary frustration. Some see it as only a matter of time before a man with Honnold’s appetite for risk finally gets his own sad news headline. For people with a certain, entirely valid state of mind, Free Solo cannot just be the exhilarating tale of a successful milestone in mountaineering history. It cannot be because its subject is still out there scaling crags and cliffs, heedlessly and ropelessly, as we speak. Unflagging in his pursuit of what Honnold calls “the edge” and unprotected by any safety precaution outside of his own godlike physical prowess. For some, I think Free Solo is a so-far incredible story still waiting for its sour, tragic conclusion, whether that comes months or years from now. And that is certainly a possibility. Alex Honnold admits it in one of the film’s first lines of dialogue. The film even contains a montage of highly accomplished free solo climbers who have met their fateful ends in recent years. Tommy Caldwell, Alex’s mentor and training partner (and the first man to scale El Capitan’s Dawn Wall, as covered in 2018’s very good The Dawn Wall) notes with somber matter-of-factness that he has lost some forty friends and acquaintances over the years to climbing accidents. Free Solo may offer some of 2018’s most ecstatic, tingly thrills, but it also well documents how much death hangs over the sport of free solo climbing. Free Solo is not just a document of Alex Honnold’s historic triumph (which occupies the film’s last 20 minutes) or even just about the strenuous training process. The filmmaking team, all of them close with Honnold, support him fully but they worry about him. Free Solo is very much a meditation on the risks inherent in this unforgiving sport. Alex likens it to a brutal yoga class where failing to hold the position for even a split second means that you die. Alex Honnold is a good-humored, charismatic enigma of a man. He is well-spoken, smart, and congenial, but there is an aura of quiet melancholy about him too. The taxing nature of his pursuit requires him to be obsessive, but he seems to have a single-mindedness that can seem almost alien. It is something that goes beyond the kind of all-encompassing focus required of most professional athletes. Alex mentions that his father had Asperger’s Syndrome (or the disorder formerly known by that name) and it seems like Alex might have his own affable, high-functioning version. When others fret aloud about him, his eyes reveal a quizzical, patient, amused kind of annoyance. He understands human beings worry and care for each other, but he also can’t quite grasp what all the fuss is about. For Alex Honold, all things are secondary to his life’s work. His wild, siren-like obsession may belong more to the realm of the tormented artist than the expert sportsman, though maybe not. Maybe, at Alex’s level of physical perfection, the difference between artiste and athlete is negligible. Free Solo is about athleticism pushed to the level of mad, keening poetry. He is a fascinating and hugely endearing figure, Alex Honnold. Free Solo sometime plays his unwavering dispassion for comedy (the entire group of people who populate the film are likable, good humored people and the film graciously invites us to laugh often enough that we don’t pass out from anxiety). But that dispassion is also just a key part of his psychology. His dark, sleepy eyes, occasionally seeming like those of the world’s friendliest shark, are imperturbably fearless and don’t blink often. They are the eyes of a hell-bent perfectionist who cannot fathom allowing any emotion, insecurity, or fear come between him and the goal at hand. And, of course, he is right. When, as Tommy Caldwell notes, anything less than a gold medal performance means instantaneous death, there’s really no choice but to make every other consideration a secondary priority at best.

Nonetheless, Alex Honnold is anything but an antisocial person. We are not watching a film about a robot, but someone whose mind and body are constructed in a far different way from anyone you are likely to meet. Alex is beloved by his friends (who co-directed and lensed the film) and by Sanni McCandless, the bright, gregarious outdoors blogger he has been dating since 2015. And this is where the film finds something of its tormented soul. Alex may have the passion of so many high risk dreamers, the kind that allows him to conquer his fears and place the task at hand above all emotional concerns. But he is not the only person in the film. And, for as much as he may assert that solo climbing El Capitan is what matters most and that he alone will accept the consequences, it just cannot be that simple. When we allow people into our lives, we must necessarily accept the fact that our actions touch more than ourselves. And this is not to say that the film is really critical of Alex or his goal. It just truthfully acknowledges that having a friend or significant other who does something this high risk for a living is grueling. It’s grueling even for the many friends of Alex who actually undertake dangerous climbs themselves. Every member of Alex’s inner circle knows that this is his dream. Nobody here would ever think of talking him out of it or trying to throw their bodies between him and his beautiful, perilous grail. They are just worried, as they naturally should be. Worried about a person they love because that’s what people do. Sanni McCandless worries of never seeing him again. His best friend and mentor is beginning to have graphic nightmares of Alex dying. And nobody is taking it worse than Jimmy Chin and the camera crew, who not only might bear personal witness to their friend’s grisly death but could have to bear the guilt of somehow contributing to it. What makes Free Solo a great film beyond the stunning athleticism of its final act is how it builds its human world. It does not begrudge Alex his choice. It seems scarcely possible for Alex Honnold to not do what he does. But it also softly insists that, however much one wants to follow their own rugged individualist path, we are tied to each other. And what that means, all that means, is just that we are tied to each other. We get to make our own decisions in life, but we do not get to pretend that they do not affect others. Like Into the Wild, Free Solo sensitively considers the effect that restless adventurers and thrill-seekers have on those who love them. It weights their headlong thirst for independence and excitement against the hopes and fears of those who love them and want them to live. The attention to the full human element of Alex’s undertaking makes Free Solo immeasurably richer than it would be if it were solely about the big ascent. I didn’t expect that any element of the film could stand next to the sheer, awesome scope of the big moment it is building up to, but these quiet, relationship-driven scenes are completely engaging in their own intimate right. I do not know what kind of documentarians Vasarhelyi and Chin are outside of their niche climbing world, but they understand this little subculture to a tee, physically and emotionally. They infuse it with a beating heart and people you deeply care about 91 minutes later.

And again, as curious and sometimes inscrutable a figure as he can be, Alex Honnold is nothing less than human himself. An atypically unemotional and clinical breed of human? Sure. One whose amygdala (the part of the brain that processes fear) shows essentially zero activity? According to a scan, yes. But Alex Honnold is still very, very human. He is in fact one of the funniest, richest, most vibrant characters to appear on screen in 2018, fictional or real. And while he may look quizzically upon his worried peers and fail to fully grasp the reason for their fraught emotions on a gut level (“They’ll be fine,” he says nonchalantly about the prospect of his untimely death), Alex is still flesh and blood. One of the film’s most gripping arcs is seeing some of his unflappable cool exterior start to crack as he lets Sanni into his life. He sustains an ankle tear on a practice run and starts to wonder if his newfound emotional vulnerability (vulnerable by his standards anyway) is compromising his focus. He also starts to wonder if allowing his good friends to film his feat, and thereby act as witnesses to his challenge, will throw off his courage or make him act hesitantly. When Jimmy Chin watches Alex abort an early attempt to free solo El Capitan because his heart isn’t it, it gives the co-director comfort and a new boost of resolve to help his friend. This is maybe the single most terrifying endeavor I’ve ever seen on film. Tommy Caldwell informs us that the people most freaked out about what Alex is attempting are the high-level professional climbers who know exactly how unforgiving the climb is and just how easily something could go wrong. “It’s kind of reassuring, that Spock has nerves,” Chin says with a weary smile. Free Solo is honest about the human toll this kind of high risk activity has on people, even those with veins icy enough to do the actual climbing.

All of which is to say that Free Solo is a thoughtful, emotionally intelligent film. If, God forbid, tragedy were ever to befall Alex Honnold, I don’t think this film would suddenly become a terrible, haunted thing. I think the film would still hold up as something magnificent and noble because it is so clear-eyed about its subject and his motives. It knows this sport is crazy, but also reveres the sheer beauty of what Alex is doing and respects his intelligence and Herculean talent. We see that Alex Honnold knows the costs of this way of life better than anyone. He is thoughtful and realistic about it. He is not Timothy Treadwell wading out past his depth, hunting down his own undoing. He is probably the most qualified person in the world to practice this terrifying art, if anyone ever can be. And with the human cost and all that other weighty business attended to, Free Solo leaves the ground and spends its last 20 minutes being so indecently awe-inspiring and spectacular that there really aren’t words for it. The truth is that Free Solo would be a perfect film if it were nothing but an abridged document of Alex Honnold’s coup on El Capitan (he completed the whole thing in a swift three hours and fifty-six minutes). Like seeing old video of one of Harry Houdini’s escapes or Philip Petit’s World Trade Center wirewalk or Muhammad Ali’s fights, the very act being captured here is a rapturous, historic work of art unto itself. Free Solo is a gift to future generations. An awesome record of humankind doing something so splendidly, fearsomely glorious that it brushes hands with the Divine. What can one even say? This is simply breath-held, tears-welling-up-in-your-eyes amazing! And you find your palms sweating from the unholy strain of watching this man will himself to stick to this cliff face. But you also find yourself agreeing with Alex’s mother’s sentiment: how could anyone try to hold him back from this? Each of the climb’s six phases (or pitches, as they’re called in mountaineering jargon) is clearly laid out to us so that we understand the strategy and the stakes. One part of the climb involves having one of your arms essentially devoured by a vertical fissure hundreds of feet long. Another give you no support to stand on except for tiny virtually invisible bumps in the sheer granite. And then there is the challenge that I will not spoil here. I will just say that if “The Boulder Problem” isn’t the scene of 2018, all other films should at least have to offer compelling arguments for themselves. Free Solo took me to places few films go. It wasn’t made for my cerebral cortex or even especially for my heart, though it certainly gave that organ a terrific emotional workout. Free Solo was for some part of myself, some muscle in my spirit that rarely gets exercised. The one that feeds on bewilderment, processes childlike wonder, and feeds the imagination. I giggled and gaped and sweated and groaned. There was a point in Free Solo when I heard the words “Oh Jesus” sound softly but urgently from somewhere in the theater. It took me half a second to realize the hushed exclamation had emitted quite involuntarily from my own mouth.

Free Solo lionizes its subject’s stunning achievement while also ruminating on the complicated nature of athletic obsession; how all-consuming the pursuit of athletic posterity is by its very nature. David Foster Wallace, writing about professional tennis on tennisracquets.com/collections/oliver-thomas-bags, said that people are awed by athletic excellence but that “the actual facts of the sacrifices repel us when we see them.” Perfection, he wrote, requires “[a] subsumption of almost all other features of human life to one chosen talent and pursuit.” Seen that way, it is almost shocking that Alex Honnold is as personable and as he is. The film invites us to bask in the glow of something physically stunning and close to impossible. It also invites us to consider how difficult it is for someone to be the very best of their chosen field and also remain a well-rounded person. Normalcy means something different for someone with this level of insane prowess and unwavering discipline. With Free Solo, Alex Honnold has gifted the world a godlike testament to the power and poetry of the human body, but he has also had to put most other considerations aside. For many years, he did not even have a place to call home outside his van. He has prioritized free solo climbing above everything else and, even now, he refuses to allow those closest to him to sway him from relentlessly following a precipitous athletic path. A path where death is a constant possibility, maybe even an inevitability depending on where you stand. Alex Honnold, ever clear-eyed and self-effacing, understands this possibility but there is nothing else he would choose to do instead. Free Solo is the beauty and the high cost of athletic perfection rolled into a single film. It is about the most obsessive, punishing form of perfectionism imaginable: the kind where anything less than perfection results in plummeting to your death. Free Solo can be both magnetic and repellent. It lives at the precipice of life and death. It is brilliant but also almost painful to look at. Like looking into the Sun. I don’t begrudge anyone who can’t bring themselves to watch Free Solo; who find what Alex Honnold does for a living too reckless and disquieting. But to see the best artist in their field paint a masterpiece across the world’s most beautiful cliff face is also unquestionably beautiful. 2018’s best documentary is the stuff of Greek myth. If it’s forbidden fruit, it has already been picked for us and there’s no good in letting it spoil. I could not bring myself to resist it.