Around five years ago, I had a little epiphany watching The Big Lebowski for the umpteenth time. It was a warm summer Saturday night and I was watching it outside on a good friend’s patio. I had a paper plate full of perfectly cooked steak in one hand and a sturdy little cocktail in the other and I was really enjoying letting the Coen Brothers’ shaggy comedy masterpiece just wash over me. The way you only can when the sound and feel of a film have become second nature to you. That was the night I realized there are some films that have a musical kind of quality to them And I don’t mean that they literally are musicals or even that they necessarily have to rely heavily on music. What I mean is they have a sense of rhythm and pacing in their dialogue and their sound and their editing that is akin to listening to a song. It feels natural in the way that only great music does. They can be appreciated just for the pure sensory pleasure of how they sound and feel; how all the parts just click together. I think this is something that Joel and Ethan Coen grasp better than any other modern director I can name. They delight in cadence and subtle pauses and repetitions. Images and phrases pop up again and again like refrains. It is a huge reason why, if pressed, I would call the Coens my favorite living filmmakers. Their films are not always easy viewings. They have a fascination with bitterness, folly, and human cruelty. But there is an ease I feel in watching them. Regardless of subject and theme, their films hum along like finely tuned symphonies. They are cohesive not just as narratives, but in the way it feels to sit back and take them in. And that effortless sense of rhythm and timing is in evidence once more in their musically titled Western anthology film The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. I initially watched the film when it debuted in October of 2018 and I liked it fine. Still, I told myself it was “minor Coens” and moved on. Then, over the next day or so, a thing happened. A thing I would call funny if I hadn’t seen it happen with so many Coen Brothers films in the past. I kept repeating lines to myself and poring over scenes in my brain. So I saw it again a few days later and realized I maybe kind of loved it. Then I saw it a third time a week after that, under the pretense of wanting to show it to a friend. So now, seven months later, in classic Coen Brothers form, the film that I initially deemed a worthy trifle is one of my very favorite films of 2018 and holds the honor of being the 2018 film that I have watched most often. That would be seven times as of this writing. Like a great album, I’ve reached the point where I feel I can put it on any time. Its dark, funny, soulful rhythms already feel so perfect and intuitive to me that I feel like it’s been around for decades. When you’re the Coen Brothers, even your so-called minor works have a way of quickly feeling classic and timeless.

I’ll be only the 612th critic to point this out, but one of the major achievements of The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is that it brings distinction to a genre of film with an awfully spotty track recod. That genre is not the Western (to which the film obviously belongs) but the anthology film. Films composed of multiple shorter films set a tough hurdle for themselves because the quality of each film inevitably varies. Thus, even anthologies with some dynamite entries usually face the problem that the good entries just throw the lower quality of the mediocre entries into starker relief. At the risk of damning with faint praise, Ballad of Buster Scruggs is helped greatly by the fact that it has no duds. My pick for the weakest of the six chapters, the James Franco-starring bank robber tale “Near Algodones”, is a beautifully crafted (every last one of these films is a master class in shot composition, scoring, editing, and costume design), morbidly funny piece of work that gets its business done in a satisfying terse ten minutes and concludes with a poignant bit of gallows poetry and one of the sharpest punchlines of the year. It also makes its minor splash early, for it is only the second entry in the anthology. The first, and most purely funny, entry is the titular “Ballad of Buster Scruggs”, the tale of singing cowboy (played with equal parts genial charm and gleeful menace by Tim Blake Nelson) with a knack for getting into deadly, outlandishly gory fracases wherever he goes. It is an early promise that this anthology will be about the ever-presence of death in the Western and how that death tends to be either glorified or mourned based on who is doing the killing or dying. The third film, the chilly and smart “Meal Ticket”, is about the co-dependent relationship between a traveling theater impresario (a taciturn and very Irish Liam Neeson) and his one source of livelihood, a limbless British orator (Henry Melling, formerly Harry Potter’s spoiled stepbrother Dudley Dursley, now all grown up and acting up a storm). It is about their struggle to eke a living out of their highbrow trade over the course of a harsh Colorado winter, and about the Neeson character’s temptation to turn to more steady means of making ends meet. The fourth film is the splendid “All Gold Canyon”, based on a short story by Jack London. It stars musician and occasional actor Tom Waits (one of my very favorite artists in all recorded music) as a humble, grizzled gold miner, who may have finally come upon the fabled mother lode late in his life. In a film that looks hard at man’s greed, this entry is the most joyful, generous and hopeful. It is rather simply the story of a gracious and hard-working person finally receiving some reward for his faith and perseverance and it stands out like a beacon of warmth in a film that is overwhelmingly about the cold facts of mortality and human selfishness. The fifth film, probably my favorite of the whole lot, is “The Gal Who Got Rattled”, the story of Alice Longabaugh (brilliantly played by Zoe Kazan), a shy, self-effacing young woman traveling along the Oregon Trail in a covered wagon with her patronizing brother. She is traveling to Oregon’s Willamette Valley in the hopes of receiving a marriage proposal from her brother’s potential business partner. When her brother passes away from cholera less than halfway into the trip, Alice must rapidly become a braver soul while also seeking help from the two men in charge of leading the train. One of them is a jovially soft-spoken, earnestly helpful younger man named Billy Knapp (Bill Heck, subtle and marvelously likable). The other is his older mentor, a trail-hardened, tight-lipped frontiersman named Mr. Arthur (Grainger Hines, in a terrific performance that speaks volumes even when the character says almost nothing). The film’s depiction of frontier travel is beautifully unforgiving, with the team of wagons moving like frail, tiny lifeboats along the endless sea of pale grass. But what makes this entry truly stunning are the lovely performances and a central relationship between Alice and Billy so tender, open, and sweetly honest that it positively hurts to watch. Finally, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs closes with “The Mortal Remains”, a ghostly, moonlit stagecoach ride shared by five passengers (and one wanted man’s corpse strapped to the roof) that spin’s the film’s themes of uncertainty, mortal struggle and death into their most eloquently overt form. This epilogue is like a short, spectral one-act play full of heighted ruminations on the passage from life to whatever comes afterwards. As with so many Coen pictures, the Reaper’s presence never feels far away and the Almighty’s role in human affairs remains tantalizingly unresolved.

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs finds the Coen Brothers returning to their old pet themes of death and the great beyond, and reflecting upon them in the way that an old blues picker might sing his hundredth song about losing his woman. The fact they’ve trod this ground before has not dulled their wit and imagination. This kind of thematic repetition energizes the Coen Brothers. They have certainly been to this well before but the fun of it and the poignant impact of it lies in how creatively they can keep riffing on old material. This is really about nothing so much as Joel and Ethan Coen taking on a musty old genre (the Western, which they so skillfully mastered and mined for pathos in 2010’s True Grit) and spinning clichés into gold. They are interested in how so many of their favorite subjects (from death to greed to the lonely quest to find the rare human being who doesn’t want to rob or kill us) are part of the essence of this old genre. “Ballad” is really the right word for this film. This collection of quintessentially American tales is like its own little haunted bluegrass album. The tunes change, but there is a cohesive throughline of mortality and human fallibility that runs through it. Like the blues, it is many stories that are sort of all the same story on some level. Fittingly, the film features a number of old blues numbers (“Cool, Cool Water”) and classic traditional songs (“Mother Machree”, “Pills of White Mercury”) as if to announce the company it wishes to join. The Coens have made their own classic blues song in film form, filled with its own ageless beauty and melancholy. Their song, like so many others, goes like this. Human beings are born under an impartial, unfeeling sky. They sweat and fret and search as best they can for some kind of comfort in each other. Sometimes they find it and sometimes they really, really don’t. Sometimes they only find selfishness and pain. People hope and love and struggle on. But only one thing is ever set in stone for them. As Billy Knapp tells Alice Longabaugh, in an intimate, hushed existential fireside chat, “only in death do we vouch save certainty.” Like the passengers in “The Mortal Remains”, we all share this rattling, lurching stagecoach together and we do not know when and where the voyage will end. The one certainty we have is that there will be a final destination. As gruff Mr. Arthur might say, we aren’t going to go on with this battle all day. The fact, simultaneously chilling and strangely reassuring, is that everything comes to an end. And if there’s one other bit of cold comfort to be had, it’s this: though the quality of the company we share may vary, we are all going to the same place as one human mass. Saints, sinners, robbers, prostitutes, tycoons and beggars are all going to the end of the line together.

And if the notion of the squabble of humanity, in all its backbiting and thieving, sounds cynical and bleak, it certainly is at least a little bit. The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is caustic and condemning in that gallows chuckle of a way the Coens have. But the Coens have never been about simply writing off the human race as a bunch of heartless bastards. The film’s most metatextual moment arrives in the first five minutes of the first entry, when Buster Scruggs unfurls a Wanted poster and shakes his head in dismay at being nicknamed “The Misanthrope”. For any diehard Coens fan, it’s a complaint that has dogged the brothers for the length of their careers. The idea that they are looking down on humanity in disgust and condescension. Their cheerily violent, singing cowboy stand-in scoffs at the very idea. “I don’t hate my fellow man. Even when he’s tiresome and surly and tries to cheat at poker. I just figure that’s the human material.” The Coen Brothers have sometimes been accused seeing the very pettiest and worst in mankind. It’s the price they pay for spending so many decades as the cinematic poet laureates of desperate grifters, doomed conmen, impotent schemers, and downtrodden wage slaves. They have a beautiful way of capturing the seedy, the trapped, the greedy, and the unsavory. But it’s always been a failing and a grievous misreading of their work to reduce them to that kind of sad, sweaty cynicism inherent to some of their most memorable characters. As with other great Coen films, the violence and avarice in Buster Scruggs don’t feel cheap and exploitive. It resonates deeply because the Coens always have a sense of rueful longing for the world as it maybe could be. They see the selfless, striving and good in this world too. Buster Scruggs may refer to “the human material” dismissively. He feels he knows too much of mankind’s meanness to ever let himself be disappointed by it. But the Coens are a tad more hopeful, or at least more soulfully conflicted, about people. Sometimes they see just enough decency in the world to make the next senseless act of human apathy or cruelty land with an even more sickening thud. But that disparity between the best and worst in humanity makes their universes strangely optimistic and rich. There are thin layers of virtue interlaced with all the selfishness and vice. The Coens see that the good-hearted Marge Gundersons must share this world with the weak-willed Jerry Lundegaards and pessimistic Llewyn Davises; to say nothing of the murderous Anton Chigurhs. What makes life such a beautiful and gutting experience is that each person has the capacity for goodness and monstrosity. And if the kindly Marges of the world really are outnumbered by the less benevolent characters, that only makes the presence of their generosity and empathy all the more precious. If The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is largely about death and greed and foul dealing, it is also about the things that stand in opposition to all that. It is, in some small way, about the oases of life and kindness, even if those can feel like tiny, helplessly outmatched outposts in a desert of indifference and hostility.

Three decades into a dazzlingly rich and diverse career, the Coens are still working out just what “the human material” really is. When you count us all up, who are we? How many of us are scared and self-regarding like Liam Neeson’s faltering theater operator? Or rash and impulsively mercenary like James Franco’s bank robber? How many are thoughtful and righteous like Zoe Kazan’s Alice or industrious and honest like Tom Waits’ prospector? Or are most of just Buster Scruggs: self-interested forces of chaos just looking out for number one, cutting a haphazard trail of destruction through whichever human life is unlucky enough to run afoul of us? Regardless of how each of us answers that question, the best parts of Ballad of Buster Scruggs propose that we are all bound together in this human play, whether we like it or not. We really are traveling the same dusty, red path toward life’s end, and we have the whole gamut of free will to draw from. We can abandon each other or hold each other; rob each other or lend a hand. That is what makes “The Gal Who Got Rattled” my favorite entry in the anthology. While it goes to some truly sorrowful places by the end, the connection Zoe Kazan’s conscientious spinster and Bill Heck’s lonely, sweetly earnest wagon leader find out there among those endless plains is one of the most humane and sincerely lovely things I saw all year. Ballad of Buster Scruggs is very much about the lonesome, solitary fate that awaits us all at the end of our respective trails. But, until we get there, we do not have to be alone. We may occasionally be a cowardly, self-serving, uncharitable lot. We human beings. But we still have each other for better or worse. And it can be for better. We have the power, even at our most venal and base, to be of comfort to each other. And, when you think about it that way, it’s hard to come away from the Coens latest rich treatise on humanity feeling too much misanthropy for our species.

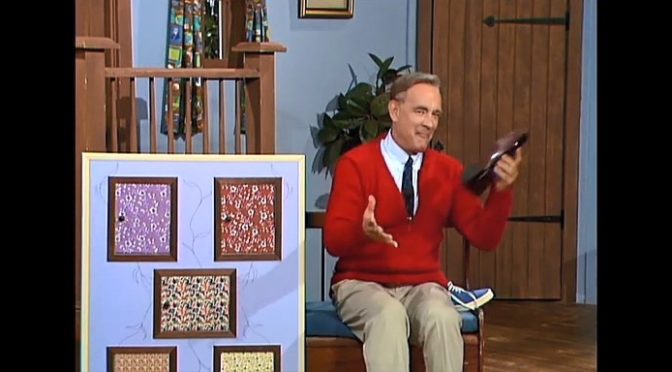

The Coens have always had playful, restless imaginations. It should come as no surprise then that, in the midst of a fairly focused essay on death and the West, they find time to break away for some thoughtful digressions on other topics. In the middle of the film, they take time for two very different examination on making art and the thin line between failure and success in artistic endeavors. The first of such digressions is the almost apocalyptically bleak “Meal Ticket”. Neeson’s frustrated money man and Melling’s helpless quadriplegic thespian are both locked into a relationship where one needs the other. But the Coens have no doubt about whose need is more desperate; about which party, between artist and benefactor, is most vulnerable. It is a beautifully acerbic and morbid reminder that, like everything else on this Earth, Art exists at the mercy of scarcity and humanity’s baser instincts. The next film, “All Gold Canyon”, chases its predecessor’s jet-black pessimism with a golden shot of joy and slowly building enthusiasm. While the tale of an experienced prospector plying his trade with a pan and a pick may be less overtly about the artistic process, the implication is very much there. This entry radiates a beatific pride for the virtues of knowing your craft and putting your all into it. Tom Waits’ sweetly raucous 49er pans and digs and strains his creaky body without complaint, swept up in the joyful immediacy of hunting the big score he’s spent his life pursuing. He is certainly thinking about money, but he also seems elated to just be doing his job well. “All Gold Canyon” is a transcendentally positive ode to loving what you do for a living and getting the details right. It is a cinematic rendering of that old Quaker saying: hands to work and hearts to God. It may also be the film’s most powerful piece of metatextual commentary. It is not hard to look at the Tom Waits character, sweating and smiling and merrily cursing up a storm, and also see the Coen Brothers. Two grizzled veterans of cinema just plugging away, delighting in the chance to wake up and do what they have spent the last three decades getting better and better at. This may be the sweetest, most optimistic piece of work they have ever produced. They may have spent many years sadly shaking their heads as hapless, selfish men who throw away their lives and souls for a little bit of money. But this time they do not begrudge their protagonist his modest little fortune. It may be because the film is about more than just the naked quest for gold. Here, the pure pursuit of something seems to be mean more to the character than the mere reward. The Coens have never cared too much for golden treasure. But, after thirty-four years of beautiful, bruising films, they know that there are some riches worth digging for. Some fortunes are worth losing a few drops of blood over.