In writing up my #20-11 films of 2014, I did not plan my list around any kind of running theme. That said, the best movie of the year and the 20th best movie are kindred philosophical cousins. Both are closely observed examinations of time’s inexorable passage, though one is fictional and the other is a documentary. Both make use of subtle stylistic devices to explore the sprawl of time’s relentless course. They are not merely observations of time passing, but meditations on what it feels like to be vessels swept up in the current of time. To bear witness to the way time seems to undulate and swirl like a heat wave. The way time plays games with our expectations for it, sometimes easing us along, sometimes hurtling us forward with great speed. At certain points, both films observe the dynamic between children and adults, the young and the elderly. Both involve us as passive surrogates in the torrent of time, and that approach has earned them the distinction of being uneventful by their detractors To me, both are proud examples in their own genres of a very unforced kind of humanism; a willingness to watch subjects with a curious, sympathetic, but unobtrusive eye. Both involve unique “gimmicks” and, in both cases, the stunt is so inextricably bound up with the substantive content as to seamlessly blend style and subject. For a certain kind of film, style merges with content, transcending it, shaping it and informing it.

I have begun this review cryptically to protect the identity of my top film of the year. Those who know me, and a great many cinephiles who do not, can probably hazard a safe guess as to what will receive the honor. While I cannot yet speak to that film, I can say that the presence of the beautiful, serene, and entrancing documentary, Manakamana at the back of my list brings great closure to a somewhat maligned year. I have personally accused 2014 of being slighter than the two years that preceded it, and I maintain that view. On the whole, the year certainly did not match the enormous harvest of 2013, but I feel that was always going to be a daunting task. That said, if we are in a sparer year for great cinematic works, maybe it just goes to show that film is as susceptible to cyclical forces as corn crops, hurricanes, and human beings. It is a notion that the unfailingly patient Manakamana would doubtlessly agree with. Even art is governed by the ebb and flow of the universe. All of which is to say that if this fine, perceptive, and hypnotic documentary is the outlier in my Top 20, I can make peace with 2014 and curl up contentedly with all that was interesting, vibrant, and yearning about its numerous beautiful and accomplished films.

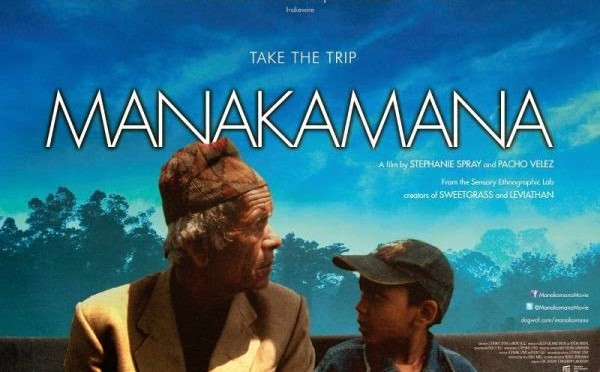

Manakamana comes courtesy of the Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab, the same group of rigorous film scientists that gave us last year’s mesmerizing fishing documentary, Leviathan. The fact that I can sincerely write the words “mesmerizing fishing documentary” feels about as intuitive as my being able to say that there now exists a great documentary about riding a Nepalese gondola. In the documentary, we watch a host of tourists, pilgrims, and animals, travel by cable car over the steep, green foothills of Nepal to the Manakamana Temple, a popular religious site. The destination is both important and yet perhaps also irrelevant. It is every party’s immediate motivation at the moment we meet them, and it is particularly significant to a car full of goats, ascending the mountain to take their roles in the Temple’s animal sacrifices. However, we never actually see the temple. Instead, the film is confined to the eight-and-a-half minute cable car trips that shuttle travelers to or from the pilgrimage site. We watch six cars go up and five cars go down over the course of less than two hours. Each ride begins and ends in the dark of the docking station. What the passengers say or do not say, do or not do inside the gondola will vary, but the limited duration of the trip will not. As passengers, they cannot alter the finite nature of their trip. They can only choose what they say or do within that limited space. If one thinks of the gondola as a metaphorical microcosm of time, Mankamana recalls Dylan Thomas’ “Fern Hill”. Time holds them green and dying, though they sing in their chains like the sea. The film is quietly fixated on both the overwhelming insignificance and the beautiful intransience of human faces and voices.

This is where Manakamana overcomes gimmickry and becomes more than the rote process of watching passengers ascend and descend a mountain. The film effortlessly shirks the sin of being too ambiguous through the people and conversations it chooses to gaze upon. While the film, like Leviathan before it, does not offer any narration, interviews, or written text to explain its perspective, the intentness of its focus has a clarity that speaks volumes. Manakamana surrounds its temporal experiment with just enough discourse about ethereality and change that the vignettes engage with the conceit without ever upstaging its overwhelming visual impact. The sense I got was not only that of seeing the nature of beginning and end, hello and goodbye, birth and death in tiny 9-minute pockets, but of viewing miniature vignettes on history, progress, aging, and memory. In the first segment, we ride with a very old man and a very young boy. They sit hushed for the entire trip. We view young and old in juxtaposition, with not a word said between them. True to a meditative style that is both serene and buzzing, the film asks us to simply watch them together for 9 unblinking minutes.

The act of watching, more than anything, seems to be Manakamana’s chief plot and its guiding theme. We are meant to watch the passengers, some silent, some chatty, some bleating hysterically. They speak of ancient religious histories, memories of childhood, or what band they will see next weekend. Sometimes they just sit in silence, alone or in each other’s company. There are dialogues between the young and the old. Some of them ponder their youth. Many of them ponder the impact of change. We can sense years of conflicting pride and tension in the way a successful daughter now gently chastises her aging mother for making a mess of her ice cream bar. A group of elderly woman talk of Hindu parables. Two young women have a banal conversation about the climate. Two older musicians quarrel fondly and then let their instruments speak for the remainder of the ride. We watch them talk of time and we watch time hold them, if only for an instant. Many of the passengers look out at the mountains and speak of days when travelers would have to hike the steep trails to the Temple. The very existence of the gondola is a symbol that we are always moving forward. One woman says to her husband, “Things only started changing recently.” Of course, this cannot be true. Change has always been the constant. Life is never static, even if it can occasionally feel that way to the passenger.

There is something disarming and entrancing in the way Manakamana captures the finiteness of everything. We know how long each ride will last, and yet we regularly find time sneaking up on us. As the car reaches the low-hanging tree that signals each ride’s halfway point, we remember that we have just barely begun to know these passing faces. In short order, they will leave us for good. Like life itself, time seems to amble gently when we have it in abundance and course swiftly once we see the other end of the shore. Each time the cable car reached the halfway mark, I found myself asking, “Where did all the time go?” But the journey had begun less than 5 minutes ago. It is uncannily hard to make sense of or even properly describe how attached you can become to a person, group of people, or even herd of goats after you spend 9 minutes with nothing to do but look at them. Trapped in this temporal riptide, we too rarely look at those around us and acknowledge that they are being swept along beside us. Here are roughly 20 souls I had never been aware of before. And I am now writing about their insignificant tourist experiences with an overflowing heart. Without saying very much overtly, Manakamana gets at sweet and subtle truths about what is both painful and beautiful about meeting and seeing human beings. This film about having to say goodbye to people carries an implicit feeling of tenderness for the fact that we get to meet at all.

Manakamana and its thematic 2014 counterpart both remind me that the simple act of watching people go through the minutiae-laden process of being people can be a source of genuine, soul-filling pleasure. Both films make the unseen forces around us tangible. Both films filled me with a tranquility that I have rarely even found in the solitude of nature, much less in a semi-populated movie theater. Manakamana captures the invisible hand of time, while seeming to record nothing of any great event. It is a serene ode to mortality. That serenity feels true to the otherworldly calm of the film’s environment. It can be no accident that a film that watches passengers ride a suspended tram to a holy site casts its own spell of peaceful bliss. As an avid documentary lover, I am gratified to be able to say that the genre cannot only inform, incite, and pontificate, but also provide a bracing, meditative experience. Manakamana is a superlative example of how documentary film continues to grow and evolve after so many years. It is a work of art that ripples and shimmers and sighs. Within its isolated pockets of time, there are long strands of memory and unspoken histories. We are only looking at a small hole in the ice. The currents that burble past began their course long before they reached us and will continue on after they have passed out of our sight. The whirring cogs and groaning cables of the gondola will still carry human lives up to the mountain, after we have said our last, dark goodbyes.