Everyone take a bite of your nearest mutton leg (or vegetarian alternative), hoist a pewter mug full of mead, and roar out a mighty toast to the Year of Our Lord 2021, one of the greatest on record for Medieval Cinema! I’ve never been automatically in the tankard for tales of ye olden days, heavy with sword fights and knights and kings. If I’m being honest with myself, most of the Robin Hoods not featuring photogenic foxes or Mel Brooks songs have been non-starters for me and, like many, I had consumed my fill of Game of Thrones years before it ended. But when a good Middle Ages-adjacent tale works it works, and 2021 gave us a few special films to stir up the raucous warrior blood in the Medieval film genre. Ridley Scott gave us a wickedly modern skewering of fragile masculinity in The Last Duel and David Lowery may have made the best Arthurian movie of all time with The Green Knight. And, surprising nobody who has seen the delicious texture and tone he has brought to period pieces like True Grit, Inside Llewyn Davis, Barton Fink, O Brother Where Art Thou, The Man Who Wasn’t There, and Miller’s Crossing, Joel Coen gave us another grippingly nuanced and inventive look into bygone times with The Tragedy of Macbeth. He has given us a reading of Shakespeare’s violently engaging masterwork that howls and moans with all the maniacally ominous glee of a crackling ghost story. A bloody and foreboding yarn so cynical and bleak that you almost feel elated by its sinister, primeval majesty. Both The Green Knight and Coen’s Macbeth aim to make us feel unsettled from the first seconds and in similar ways; a raspy feminine voice croaks archaic poetry at us from offscreen in a way that both repels us and invites us to lean forward to enjoy the old school pleasure of a dark, dangerous story. Both got right under my skin and made me light up like a little kid huddling by a campfire. Apparently Old World sagas recounted with heaping helpings of uncanny dread is a pleasure center I had forgotten I had, and one I hope to have engaged more in the near future. As I have noted before, 2021 gave a renewed good name to the period piece by taking journeys into history that were both aesthetically engaging and also worked with feverish imagination to connect those stories, costumed in period garb, to the present day. And very few films did a better job tying a centuries-old tale to the here and now than Joe Coen’s masterful voyage into Shakespearean calamity.

With some minor abridgements, The Tragedy of Macbeth is largely the same deliciously fatalistic “Scottish play” many of us probably first came across in high school. MacBeth (a terrific Denzel Washington, as weary and as ill-tempered as an old grizzly bear) is a great warrior and loyal subject of King Duncan. At the story’s beginning, he is fighting off the last of his leader’s enemies in a great war. For his valor, he is to be named the Thane (a land-holding nobleman) of Cawdor. On his way to receive his promotion, however, he and his war buddy Banquo come across three old “weird sisters (Coen’s rendition proposes the could also just be 3 parts of one troubled old woman’s Gollum-like personality). The witchy trio present Macbeth with the first of several prophecies: he shall hereafter become King of Scotland. This oracle gets into Macbeth’s head so thoroughly that the wine of his new title later that evening (King Duncan proclaims that his son Malcolm will be Scotland’s next ruler) turns to vinegar in his mouth. Instead of serving as the nice gold watch for decades of loyal service to the Crown, Macbeth now regards it as a crushing rejection.. Macbeth treks home to Castle Dunsinane and Lady Macbeth (Frances McDormand, having a lot of fun with her characteristically brusque take on the role) with blood-thirsty and bitter thoughts already stewing in his mind. King Duncan will soon be visiting them in their castle and their disappointment and desperation plants a vicious seed in their minds: kill King Duncan and claim the throne for themselves. And once that treacherous deed is done, the remaining bulk of the story is all the stuff of legendary falling action. Blood stains that won’t wash out. Frame jobs and feuding. A cauldron bubbling with more noxious prophecy to poison our protagonists last vestiges of reason. A forest marching to in unison against a fortress. It’s a bitter and senseless tale that, unlike Macbeth’s late assessment of his own sorry plight, signifies quite a lot. Few stories written have such a distressingly resigned stance on man’s cannibalistic urges toward his own species and the ways that power leads human beings to drunkenly lurch in the direction of their own undoing. Macbeth was not the first bloody game of thrones written, but it has a claim to being among the finest to ever muse on man’s cruel efforts to climb to the top of the heap, even when that heap turns out to be a pile of corpses.

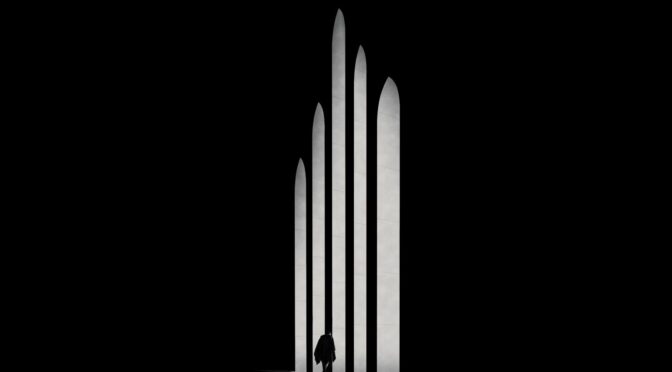

The film is shot in black and white but, Bruno Delbonnel’s gob-smackingly godly, German Expressionism-evoking cinematography makes it all looks like pure gold. To watch The Tragedy of Macbeth is to see Joel Coen plugging his own distinct sensibilities and thematic obsessions into this classic story. I found myself delighted and only a little bit surprised to discover that the Coen touch is an absolutely perfect fit for Shakespeare’s cynical saga of power. In the Coen Brothers’ first film and masterpiece, Blood Simple, one character warns another that it is no simple thing to kill a person. He is speaking in that instance of making sure the job is done, lest your poor victim survive to turn the crosshairs back onto you. But the thorniness of causing another’s death only begins there. A Host of stories from Macbeth to Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart to myriad other Coen films remind and caution us (we vicarious armchair murderers) that sometimes, even when the job is done, it’s not really done. Our trail of guilt and incrimination does not go cold just because the body does. What is Lady Macbeth’s eternal “out, damned spot!” soliloquy if not the most famous example of a character learning too late the pesky complications of taking a human life. For most, the cost of killing is so psychically consuming that self-justification becomes a Sisyphean task; one that takes up the rest of our pitiful hours.. Lady Macbeth is understandably remembered as a coldly calculating schemer, but Coen’s direction and Frances McDormand able performance help us to remember the even more tragic shred of a person she becomes in the wake of her vile act. She has thrown herself, a frail and shivering child, into a violent brawl with her own hulking conscience and it only takes a matter of hours for the beast to leave her broken and lifeless inside the fortified walls of her own castle. And, while his wife is rapidly losing a duel with her own sense of self, King Macbeth is locked in an outward battle to protect himself from the immediate consequences of murder. What that means is he must commit even more murder, in a futile race to justify himself and insulate himself from the bloody evidence pointing toward his cursed house. By the time the Weird Sisters reenter the scene to fill his head with more suffocating swamp gas, it is already far too late for his attempt at self-cleasning to succeed. The seeds of his vice are already blowing out across the fields of Scotland. Even the bloody trees know what he’s done. And they’re coming to see him about it.

The hardest thing about a good Macbeth to my mind is that both Macbeths are, on their face, despicable. The first time I witnessed Shakespeare’s Scottish play read out loud by my Junior year Honors English class, I felt something was missing. No offense to us. I remember enjoying the morbid spectacle of it all, the twisty and sinister journey of mayhem and bloodshed. But it was also a nasty piece of work and it felt pretty easy to keep a distance from the sorrow of the play because the Macbeths were such plainly greedy, unredeemable sociopaths. One can picture a particularly basic 1500s attendee of the Globe Theater walking out and saying, “Gee, I thought the writing was good but Macbeth is such an unlikable person. Why should I care what happens to him?” Well, Joel Coen is an awe-inspiring wizard at getting us to care about some of the most distasteful, unpleasant characters in all of fiction. Fargo‘s Jerry Lundegaard is an absolute monster by the end, but it feels cruel to call him unlikable per se. He is broken, sad, impotent, and dumb. But our hearts also ache for him. What makes a plan-gone-wrong story so compelling in Joel Coen’s hands is how he manages to bring us into the stunted hearts and minds of some very amoral and short-sighted people; at regarding them with a critically honest kind of compassion. On that note, I will never have much patience for the school of thought that the Coens cruelly torture their characters. On the contrary, I think they torture them with the utmost empathy and insight. We are always given the chance to relate to these people up to a point. I will here echo the critics applauding Coen’s shrewd decision to make the Macbeths an older childless couple. We would never condone what the Macbeths do. Macbeth murders a dear, old friend for the sake of a title. But we are meant to feel their sense of panic and to see their jagged little wheels spinning. We see they, like a Jerry Lundegaard or a Llewyn Davis are nearing the back half of their lives with little to show for it. Like Llewyn Davis’s box of unsold records that he must now carry with him, whatever grand dreams the Macbeths have harbored for the future have turned to burdens over the dissatisfied years. I may not know much about what an aging Scottish general feels when he is passed over for the promotion that was supposed to give his life meaning, but I can see Macabeth’s face fall when Duncan passes the monarchy instead to his son. And I can see the pain in Lady Macbeths drawn face; maybe even the painful memory of a failed attempt at bearing children. And these people are monsters, make no mistake about it. But a Coen monster is a very human monster. To put a finer point on it, it often seems to be an overabundance of the human that brings the monster out in them. And in letting the Macbeths’ low-rent disappointment sink in before the dagger plungers into Duncan’s chest, Coen ears the right to truly call his Macbeth a tragedy.

Of course, some time between the murder of King Duncan’s bodyguards and the moment one of Macbeth’s own soldiers is throwing a rival’s child from the second story of a burning house, we stop feeling pity for the Macbeths. Dismay and revulsion take over, for King Macbeth is a revolting human being. By the time he reaches the end of his bloody, savage road and the oak leaves of Birnham Wood are blowing through Dunsinane’s cavernous halls, he has gone from a pathetic, manipulated monster to a vain and entitled one. Emboldened in the belief that he cannot be taken down, he has galloped well past the likes of a haphazard bringer of death and sadness like Jerry Lundegaard and is now discussing murder tactics with the likes of an Anton Chirgurh. And when I made note of that gruesome metamorphosis on my first viewing, that was the moment I concluded that Joel Coen had made another work of genius. (Just as an aside, if The Tragedy of Macbeth is to be labeled a minor Coen film, then the time is past due to find newer and more descriptive ways of discussing those films that happen to only rank in the back half of a near-perfect ouevre.) Coen had picked up a centuries-old play and seen two separate Coen archetypes in one man: the sad sack schemer down on his luck and the hellbent avatar of carnage. Jerry and Anton, there in the heart of one classic villain. He had found in Shakespeare’s blood-soaked saga a very Coenesque story of how men are emasculated by a desire for money and respect, how they cry out to be heard and recognized as serious men, how they overestimate their faculties and conspire to rise above their stations, and how all that impotent upward striving can so often turn us into bad men. Into doomed, damned and dead men.

And being damned and forsaken by God (or the howling void that marks the absence of God, whatever the case may be) might just be the most Coenesque element that Shakespeare’s play has to offer. I thought back on the Coens’ A Serious Man protagonist and Gob stand-in, Larry Gopnik, trying mightily and sincerely to find God’s presence out in the world, fearing that there may not be a Creator to witness his ordeals or hear his pleas, and eventually learning there could be worse things out there than an indifferent and godless Universe. By the time poor, put-upon Larry is staring down a cancer diagnosis and his only son is staring up into the funnel of a tornado, Coen has posed the hypothesis that we should maybe treat the search for God with the same guarded caution as the search for extraterrestrial life. That is to say, if we assume a higher power exists, can humans actually assume that said power cares about human life or even feels positively predisposed to humankind? Must God necessarily be like the cute, grey, almond eyed aliens of Close Encounters of the Third Kind or could he not just as easily be like the xenomorphs of Aliens? In Macbeth, the would-be King starts the play thinking he’s found a miracle; that the spiritual world has pierced the veil between Heaven and Earth to bestow a glorious, regal destiny upon him. He believes he is hearing a voice, though Shakespeare, ever ambiguous and open to interpretation, never settles whether that voice comes from God, a senile or malevolent old woman, the Devil, or the demons in Macbeth’s fragile head. The only thing of certainty is what happens to the Macbeths, whether you believe the cosmos leads them astray or, like so many greedy and frail dream-chasers before them, they just doom themselves. In a Joel Coen drama, the quest for gold and power tends to end poorly no matter what logic is guiding or justifying the quest. And both Divine Arithmetic and human calculation have an uncanny way of adding up to similarly dismaying sums.