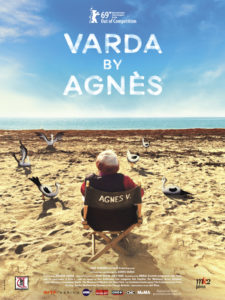

Maybe it’s that the future is becoming an increasingly inscrutable and disquieting thing, or maybe it’s that we look to the past for guidance and clues in challenging times, but, whatever the reason, 2019 had a whole lot of looking back. From personal memoirs like Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir to Quentin Tarantino’s deliciously elegiac 1960s time machine to the masterfully potent nostalgia of Apollo 11. Even some of the films that didn’t entirely work for me were sifting through the past (JoJo Rabbit and 1917 revisiting our World Wars; Joker recreating the Scorsesean grime of 1970s New York City). Above all, 2019 was a year when many of our finest directors made reflected back on their lives and careers and tried to make sense of their artistic legacies, whether directly (Pedro Almodovar’s practically autobiographical Pain and Glory) or more obliquely (Martin Scorsese reconsidering the value of the mob film with The Irishman). The most deceptively modest auteur retrospective was Varda by Agnes, which consists of two filmed seminars by the legendary, visionary, and impossibly winning Belgian-born French filmmaker (and Queen of the French New Wave), Agnes Varda. In the 21st century, Varda largely retired from her storied career of fiction filmmaking to make a handful of rapturously received documentaries. The most recent up until now was her lovely, spirited masterpiece, Faces Places, about her collaboration and friendship with a gifted young photographer with a talent for creating high-concept, building-sized portraits of working class people. As most cinephiles likely know, the 90-year old fairy godmother of cinema passed away in March of 2019, less than two months after Varda by Agnes premiered at the Berlin Film Festival. If the films released this year by Scorsese, Tarantino, and Almodovar feel like farewell letters (films that will be viewed as their swan songs decades from now, even if those directors go on to make more work), Varda’s film is more literally a goodbye; a fond reflection on what film has meant to Agnes (and what Agnes has meant to film) by a woman whose late age and cancer diagnosis must have made her aware that she only had a pittance of time left to collect her last impressions and leave us with the final pearls of some seven decades behind the camera. If anyone deserved a grandiloquent, momentous send-off it would be Agnes Varda, but she has always been a filmmaker who adores the thrill of making great art simply and with zero self-importance. A sweet, modest goodbye suits Agnes Varda, but what suits her even more is a goodbye that draws great humor, heart, and surprising emotion from its own modesty.

At first glance, Varda By Agnes resembles nothing so much as a Kennedy Center honor or some artist salute on PBS, with Agnes demurely escorting us through her own work. The film is comprised of two lectures that Varda gave in an opera house to groups of film students. Varda sits on stage, the model of sweetly impish humility that she always was, and talks to her audience about her films over the decades. Varda began as a photographer before helping to found the beyond-influential French New Wave movement (alongside filmic titans like Jean Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, Eric Rohmer, Alain Resnais and Varda’s late husband, Jacques Demy) in the 1950s. Her work included shorts and feature length films, fictional works and documentaries, photography exhibits and high-concept art installations. The only thing more diverse than the variety of projects Varda took on was the variety of her (mostly) human subjects. She documented the Black Panthers and the hippie movement in the 1960s; made realist dramas about French fisherman and giddily experimental documentaries about farmers and factory workers. In later life, she even made a video-enhanced shrine to someone’s dearly departed pet cat. She has made lively examinations about a woman’s right to choose, feminism, and the Chicano muralist culture of East Los Angeles, all of which she presents clips from and gushes about over the course of the film’s nearly two hours. It’s a film stuffed to the gills with film history, cultural anecdotes, and Varda’s gleefully erudite enthusiasm. I could have listened to her for another two hours without thinking about it, and of course the bittersweet truth of Varda By Agnes is that this is the last bottle of perfect cinematic wine this disarming legend will ever produce. But, as the film constantly reminds us, Agnes Varda left behind an almost impossibly vast effervescent treasure trove of work to rummage through. Varda By Agnes is a breathless sprint through Varda’s own personal museum; a lovable and loving look back at the life and art of a filmmaker who followed her tireless, vivid muse from her early 20s right until cancer finally stopped her at 90. It did finally stop her, but nothing, be it illness or age, ever slowed her down. Meeting Agnes Varda makes you want to live life with unflagging zest. She makes you want to go create something the instant you turn off your screen.

If there’s a way to explain the essence of this petite woman, with dark red hair that became silvery white at the top in her later years, it’s through an indefatigable love for making things. Oh, how Agnes Varda loved her job! No matter what small form it took or what places it took her. No matter how seemingly trivial or mundane the topic. Agnes Varda made plenty of films but part of what made her an irreplaceable part of the film landscape is her approachable glee for the hard, dirty work of just plain making something. She tells her audience that one of her favorite aspects of directing is the challenge of the creative process; how to make something in spite of , or maybe as a result of, the limitations and obstacles placed in front of you. Agnes Varda can talk about filming on a shoestring budget and somehow completely joyful about not having enough money. She lived for the puzzle of hands-on cinema. She luxuriated in the gauntlet of rejections and setbacks; of making it work or figuring out something that would work. As inspiring as Varda’s genius should be to a new generation of filmmakers and film-watchers, the even more inspiring takeaway from her legacy should be her joyous resolve to make art by any means at her disposal. And of course this attitude was necessarily tied to her position as a woman trying to create art in a business that, even today, is gallingly male-dominated. Agnes Varda took immense pride in her work and had very exacting standards for herself and her performers (on the set of Vagabond, her tremendous character study of a homeless woman, she had Sandrine Bonnaire practice setting up tents over and over to nail the physical realism of a person living on the road), but she also knew the limits and drawbacks of perfectionism. As a female auteur, she must have also seen fussy idealism as a luxury. At the end of the day, whether the film came out rigorously composed or beautifully improvised, Varda made sure her bold social ideas and her inimitably humane voice got heard.

To Varda, an arbitrary sense of perfection meant less than have the art be radiantly, messily human. Her art was a place where genius and endearing, vibrant humility could meet. She directed some strikingly realistic films, but she also loved to play with bright colors and music. After meeting a distant cousin on a houseboat in Sausalito for the first time, she was so touched that she instead on making a short documentary about their introduction. In that short, she shot their first warm handshake through a series of hearts cut out of red, yellow and blue cellophane. Perhaps that sounds like a cheap arts-and-craft project, but the effect is luminous and free-wheeling and unpretentious. It’s a sincere, silly and heartfelt way to sum up the simple joy of letting a new and special person into your life. Agnes Varda’s films poured in bold primary colors straight from her pure, transparent heart. She has the boldness to be utterly humble in the way she made art and in how she saw the art of others. In the film’s opening, as she sits onstage in her monogrammed folding chair, ready to begin her beautifully digressive final film, she looks up at the opera houses’ ornately domed ceiling in admiration and awe. Unlike the prickly pretense of her fellow French New Wave pioneer and friend, Jean Luc Godard, Agnes Varda never had any real ego about her art. She was humbled and excited and completely gratified to call herself an artist and to create alongside others. Her ruminations on Vagabond are partly an opportunity for her to give hearty thanks to a performer that she was hard on at the time. Another film is introduced so that Varda can bring her cinematographer up onstage to share her own thoughts. And before she can begin the final film of her career (and her fourth brilliant documentary of this century), she just has to give a sincere and humble compliment to whatever architect designed this beautiful ceiling however long ago. If Varda By Agnes is your first time meeting Agnes Varda (And my God, it should not be your last), this opening beat is charming and perfectly revealing introduction to her character. She was a director who sought to create beauty, but also found it wherever she went.

The film is also a reminder that there was maybe no filmmaker more generous than Agnes Varda. What comes through about Varda’s films, as prolific and as wildly hard and as wildly eclectic as they are as a body of work, is that Agnes Varda found beauty in people. Early in the film, she tells us that the real reason she makes films is to share them with others. The reward for her was not making her vast intellect known to the world or achieving canonization among the pantheon of legendary filmmakers (though she surely achieved both), but to share and collaborate with other human beings. As I noted in my review of Faces, Places, what made Agnes Varda a practically peerless documentarian was her ability to coax her subjects into giving something of themselves, to truly reveal their souls. The people Agnes Varda interviewed, directed and worked with always gave of themselves because Agnes was an open book and because she a pure love and fascination for humanity beamed out of her at all times. It was a vivacious, animating force that coursed like electricity through her films and that invigorated anyone fortunate enough to play some role helping to make them possible. “Nothing is trite,” Varda tells her audience, “if you film it with love and empathy.” Varda was proof that a warm and loving gaze could transform a film from its humblest ingredients into something transcendent, gloriously playful and understatedly wise. For her final Vardian miracle, she has turned that wonderful perspective on a film basic film retrospective TED Talk and, like some enchanted spell, turned this filmed lecture into a magical ode, not to herself, but to the universal joys of creating things, with and for others.

If you want to find a moment in the film that really is Varda By Agnes in miniature it’s probably that cat tomb film. In crafting a video intended to mark the sad passing of a loved one and to act as a remembrance to them, Varda neither cheapens death nor gives into its somberness. Her cat grave installation begins with a stop motion sequence of starfish, one by one, lining around the departed animal’s grave. Then, rings of seashells appear on top of the unassuming mound of earth, and then blooms of fuchsia flowers start materializing in lush bursts (all set to music by legendary minimalist composer Steve Reich). Finally, the camera pulls up from the tiny tomb like a heaven-bound spirit and ascends high into the sky, until we can see that we are on an island in the middle of a peaceful, azure sea. This simple stop motion short, dedicated to a departed cat, ends with a spectacular helicopter shot. This is Agnes Varda, working DIY magic with beach combings, then punctuating it all with something grand and exultant, and making it all feel of a piece. There was no such thing as a small subject and no wrong way to make your film if you put your whole heart into it. Whatever the method, whatever the tools you had at hand, she reminded us that clear-eyed, generous intent will see you through. Hers was a spirit you could feel bobbing playfully and curiously through every frame. And now we have another small, marvelous bauble with a transcendental soulfulness radiating at its center. Close to the end of this film, Varda underlines what an unassuming goodbye this is by referring to it as a “chat”, and indeed it is. Varda was the kind of artist who could engage you in a slight chat and somehow show you the beating heart of the world. Varda By Agnes is a droll conversation that looks upon the enormity of life and death, and renders them both simply and grandly. It’s a sweet and small-scale film by an artist who rarely needed more than a whisper to reach God’s ears.