Keith Maitland’s extraordinary animated documentary, Tower, plunges us immediately into a scene of violent turmoil. We are listening to a real news broadcast from the summer of 1966 and the film uses animation to put us inside the broadcast booth. The “booth” in this case is a four-door station wagon emblazoned with the letters KTBC, the call sign of a local news station in Austin, Texas. The man driving and speaking into the microphone is Neal Spelce, the station director. He is circling the perimeter of the University of Texas, urgently instructing people to stay away from the area. There is a sniper firing indiscriminately from the top of the famous campus Tower. Spelce is using the power of journalism to keep people out of harm’s way, but this remarkable documentary has a different journalistic aim: to take us into the melee on campus and ever closer to the gunfire. Tower utilizes a combination of old television and radio broadcasts, interviews, archival footage, and, most of all, animation to stitch together a meticulous account of one of the most sobering and sadly prescient days in American history: the day of the nation’s first official mass shooting. The film’s decision to immerse the audience in this time period without any backstory or even much context is the filmmakers’ way of recreating some small fraction of the fear and shock people on the University of Texas campus must have felt at the time. Tower knows that its viewers are all too familiar with this specific kind of horror in the present day, but it wants us to experience the birth of the American mass shooting with fresh eyes.

On the first day of August in 1966, a twenty-five-year old former University of Texas student named Charles Whitman drove to the campus, just after killing his mother and wife. Carrying three handguns, three rifles, a shotgun, and a machete , Whitman forced his way onto the 27th floor of the University of Texas Tower, killing a receptionist and two tourists in the process. From there, he went out onto the outdoor observation deck and began to fire at will at any passerby he felt he could hit. Over the course of ninety-six blood-curdling minutes, Whitman managed to kill fourteen people and injure thirty-one more before he was finally taken down by officers of the Austin Police Department. We get snippets of context and backstory throughout the film, but we never hear about Whitman’s history as a failed Marine or what he did before driving to campus or how he managed to force his way past campus security. The film’s aim is pointedly not to understand how Charles Whitman did what he did or to even puzzle over why he chose to murder fourteen innocent people. Tower instead places us with the people on the ground, who scrambled to make some sense of a senseless tragedy and did what they could to help one another through it. The film collects the traumatic memories of that day and lays them out on the floor for us to see. It is a patchwork quilt of the way human beings responded to an unprecedented survival situation. Tower wants us to imagine what it was like to be the first witnesses to this kind of savagery, but it also wants us to bring our present knowledge to bear on what we see. It wants to rewind a cycle of violence that has carried on though Columbine and the University of Virginia and the Pulse nightclub and understand the roots of America’s struggle with mass shootings. Moreover, like this year’s Jackie, it wants the viewer to think critically about we piece together and process tragic stories, individually, journalistically, and as a nation.

The very idea of a mass shooting was almost impossible to fathom before August 1, 1966. Going back to the first mass shedding of blood in our domestic history allows Tower to take a close look at how both people and their journalistic institutions react when the unfathomable happens. We learn that two students walked unknowingly, even eagerly, into harm’s way because some hapless reporter informed them that the shots were coming from an airsoft gun. A University of Texas professor heard the shots and assumed they were firecrackers left over from the Fourth of July. Our human brains are wired to analyze information and fill in the gaps with whatever makes sense to them. They are bound by the conceivable. On that day, the term “mass shooting” was not part of our cultural lexicon. On that lazy, humid summer afternoon, the thought that someone would be firing arbitrarily at innocent passersby was simply not in the realm of the possible or even imaginable for most people. Tower is fascinated by how we process an event when there is no precedent for it. One officer sheepishly admits that he looked up at the one-thousand windows in the Tower and imagined an army of one-thousand Black Panthers. Some combination of the media and his own skewed understanding of the world allowed this man’s brain to visualize a full-scale African-American revolt, while the image of a single, sociopathic white man with no motive behind his actions never crossed his minded. That seed had to be planted in his imagination, in the imaginations of University of Texas students, and finally into the national consciousness. Even after the situation became clear, the Austin Police Department still sent in supplies of tear gas instead of shotguns. A news station ended up falsely reporting that a young paperboy had been killed. Blessedly he survived, but not before his poor parents spent three hours believing him dead. And Tower presents none of this to be judgmental. Tower shows all the chaos, misinterpretation, and sloppy responses in order to posit that responding to a disaster is a messy process. Sometimes we spend days, months, and years trying and failing to fully grasp an event like the Tower shooting.

What makes Tower both a rigorous film and a generous one is that it takes in all the error and the misunderstanding and views it all as a fundamental part of being human. It opts not to show Charles Whitman because it views the real story of the Tower shooting in the teeming tapestry of people who moved about the campus below him. Tower presents a rich cast of characters who each responded to the terror in his or her own different way. It sees both fear and bravery through clear, empathetic eyes. One woman recalls watching frozen at the window of the English Building as other students raced outside to bring a dying police officer a drink of water. She remembers being stunned to see that people could summon themselves to do that and just as stunned to learn that she was not one of them. With sad candor she says this was the moment she realized she was a coward. The movie does not add anything to this. The point is not to judge, but to see how a collective tragedy gave a young woman sobering insight into herself. The intent is not to weight the morality of any individual’s actions during the unthinkable strain of a survival situation, but to observe that people are diverse in the way they handle stress. Some run headlong into danger while others are bound to the spot by self-preservation. Tower is a film with a great curiosity for the many shades of humanity. Even the acts of heroism the film shows are presented in a complex way. When asked if he was going to accompany his fellow officers out on to the observation deck to disarm the gunman, young Officer McCoy responded, “Well, I guess I don’t have much choice, do I?” Of course, he did have a choice, just as those who stayed out of the line of fire had their own choices to make. Nevertheless, Officer McCoy, being whoever Officer McCoy was deep down inside, was inclined not to see choice in the matter. Or maybe he just told himself that for fear of what he might do if he did have a choice. Every decision is the result of the myriad, intricate psychological forces within each person and Tower honors those choices, be they brave or fearful. They are testaments to the colorful tangle of humanity and the film pays tribute to them as the vivid, complicated antithesis to all that senseless death.

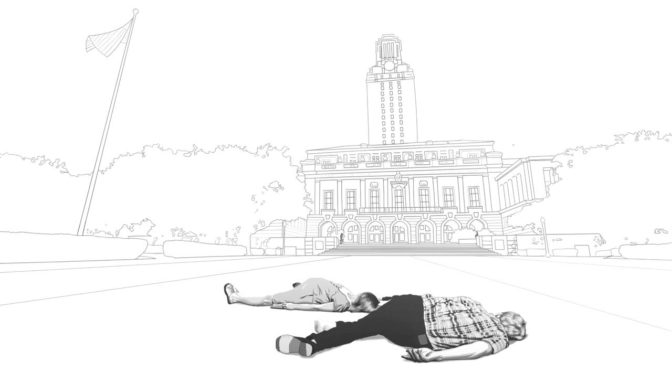

I have perhaps not adequately conveyed just how moving Tower is. This is the end result of its compassionate interest in human beings, with all their capacity for selflessness and self-preservation. Tower is a film that refuses to ever show the man known as Charles Whitman. Instead, our fullest glimpse comes from Claire Wilson, the first person to be shot. Claire ended up surviving the attack, but she lost her fiancé, Tom, and the child that was growing inside of her. Now in her sixties, Claire looks at a magazine portrait of Charles Whitman as a young child. She has no harsh words for the man. She loves children and she is now gazing down at the little boy who became Charles Whitman. She reflects sadly about how a precious child can grow up to commit heinous acts and, without hesitation, she forgives the man who murdered her unborn child. Tower focuses on the humanity that whirled around Charles Whitman’s vortex of death and this allows the brave acts of that day to take on the full triumphant power they deserve. Inspirational can be a dirty word, but Tower comes to feel genuinely inspiring without having a hint of mawkishness. It is not interested in rah-rah acts of heroism, but it is in love with our potential to be kind and good to one another. Allen Crum, a middle-aged campus bookstore employee, unwittingly became a hero through sheer Forrest Gumpian circumstance. He ran out of his store to help a boy who had been shot on his bike, but then found himself unable to go back across the street without running the risk of being shot himself. The only thing he could think to do was keep running in the other direction, toward the Tower, hoping to eventually wind his way back around to the store. And, before he knew it, he had run all the way to the foot of the building. And then he figured he should just go up and see if anyone needed his help. And so he was deputized and ended up helping to disarm the shooter. Before entering, Crum flashed two middle fingers at Charles Whitman and seeing this act of living defiance in the face of death made me laugh more cathartically than just about anything I saw this year. But the most wonderfully humane act did not involve a gun or any kind of force. It was the simple, brave act of a student named Rita Star Pattern, who ran out to the wounded Claire and lay down next to her. She lay with Claire for an hour, on scalding concrete and in plain sight of Charles Whitman, and just talked. This decision kept Claire conscious and very likely saved her life, and it involved nothing more than one person reaching out to another. Tower takes us to the first mass shooting, but it is not about killing. It is about living through tragedy as a community. In the present day, Neal Spelce, who drove around campus bravely warning people of the danger, recalls the moment they released the list of victims on air. His old boss came rushing in and asked them to repeat the list. He had heard his grandson’s name. Telling the story in the present, Spelce starts tearing up. “I just broke up now,” he stammers. “I think it’s because I have grandchildren.” This moment perfectly captures Tower’s unabashed sense of empathy. The loss of human life depicted in Tower made me break up too. I think it’s because I am human.

Tower is about a catastrophe that had no precedent in our history and how human beings dealt with an event that was then painfully new and shocking. However, as much as the film is challenging us to put ourselves in a time before mass shootings became a regular occurrence, it also holds us accountable for whatever is happening in the present day. It charges us with a sacred responsibility to learn from the past and have a discourse about what to do in the future. Because we do not live in 1966. And the next mass shooting we have will not be the first. It will not be the hundredth. Tower’s quarrel is not with any specific policy proposal, as long as that policy is not inaction or silence. Tower holds particularly severe censure for those who are not willing to talk about this. Late in the film, Claire has a reunion with a man named Artly. Artly was also a student at the University of Texas in 1966 and he was the person who would eventually pull her to safety. Shockingly, we learn that Claire and Artly did not meet for the first time until a few years before this movie was made. Almost fifty years passed by before they had a conversation about the trauma they both suffered through. Similarly, Aleck Hernandez, the boy who was shot during his paper route says that the occasion of the film has reunited him with the cousin who was riding on his handlebars at the time. They are both joyful to see each other again after nearly fifty years of silence. The cousin remarks that it does him good to sit down and talk about the tragedy. We get the sense that the University of Texas wanted the whole incident to just go away. They cleaned up the blood and never put up so much as a plaque to honor the people, living and dead, who went through this ordeal. Tower is not only a film about how we experience, process, and remember tragedy. It is a call to arms to never bury tragedy. Tower argues that the most rigorous and the most humane thing to do in the face of great loss is to turn to a human being and talk through the pain. As the film closes, the animated ghost of Claire’s slain fiancé, Tom, walks the campus alongside present-day students. The film seems to say that these ghosts are not unpleasant things to be feared and hidden away. They have lessons still to teach us. They were human beings with lives and people who loved them and it is right and good to remember them. Their spirits are a part of our history. Let them stay.