I often ask myself how possible it is to separate the personal from the political in art. When I was writing my Communications Studies thesis in college, we read about a theory known as “walking with the subject”. The idea was that, when interviewing people as part of a study, it was impossible for me as the writer to entirely get around the fact that I was there in the room. My very presence and the little quirks of my personality and the way I asked questions would necessarily influence how a subject responded to me. It would influence the kind of answers I got and my biases would eventually become a part of how I interpreted those answers. Walking with the subject meant that, when I wrote about my findings and my interviews, I would acknowledge my own presence and how it impacted the study. Since it was impossible to conduct a study without being personally present, the most objective thing to do was to just make the study an account of my interaction with the subject. Like Charlie Kaufman, the writer becomes a part of his own script. Lately, I have similar feelings about film criticism. I try to be as objective as I can about my thoughts on a film, but any judgment of a film is going to have a lot to do with who I am as a person. Films don’t exist in a vaccuum. Films communicate. They make judgments about ideas and concepts in the world. To like a film or dislike a film is to necessarily throw some of your own values into the stew, because how can you not? For example, I love The Godfather. I don’t just love it because it’s lushly filmed or has a great Nino Rota score. I love it because I think it says beautiful, complicated things about the nature of upward mobility in our country and because I agree with its viewpoint on them. It is impossible for me to properly review The Godfather without revealing that. By the same token, if you don’t agree with its complex ideas about financial success or find its parallels between organized crime and the larger American bootstrap mythos interesting, then it would make abundant sense for you not to like that film. We cannot remove ourselves from the films we love and choosing to love a film means making larger value judgments. And this is all a long way of saying that I think Beyonce Knowles’ Lemonade, the 65-minute film set to her album of the same name, is an absolutely brilliant work of art because I value its insights on racial inequality and because I believe that modern America still visits egregious injustices on people of color. Lemonade is a film that is both personal and political, as it expands from the smaller story of confronting an unfaithful husband to take on the larger spectre of American racism. And what one thinks of it will inevitably be a reflection of how they feel about the state of race relations in this country.

Now, to be clear, much of Lemonade’s plot is about very personal relationship struggles that resonate outside the realm of social issues. While discussions of racial inequity can be polarizing, depending on the person, I imagine there would be decidedly less controversy around the notion that infidelity can be hurtful. On its face, Lemonade is the story of grappling with, and eventually forgiving, an act of emotional betrayal. Lemonade is the story of R&B diva extraordinaire Beyonce Knowles finding out that she has been cheated on by her husband, Shawn Carter, better known as the great and influential rapper Jay-Z. As a disclaimer, I understand that there was never any confirmed account of Jay-Z cheating, and it’s obviously the Carter family’s prerogative to keep that information close to the chest if he did. Whatever happened between Beyonce and her husband, or whether anything happened at all, Beyonce has managed to create one of the rawest portraits of post-affair grief in either of the two artistic forms it occupies. Lemonade is about processing one’s turbulent emotions, and it cycles through an absolutely dizzying array of them. It is, by turns, raw, funny, blistering, devastated, catatonic, unhinged, uninhibited, and eventually generous. By the end, it becomes one of the most generous films of this or any year and it’s all backed by one of the year’s true landmark albums. The film is shot as a collection of individual music videos but knitted together with snippets of poetry (by the poet Warsan Shire, a Somali woman born in London). The film also dreamily cuts back and forth between scenes to come and scenes that have already taken place. As a lover of both hip-hop and the films of Terence Malick, I found Lemonade a joy to watch each of the three times I sat down with it. The film is broken into eleven chapters and one epilogue after the credits roll. The chapters have names with different emotional states, which recall the five stages of grief. With a diva as extravagant and ferociously flamboyant as Beyonce, it makes abundant sense that her grief cycle would go to eleven. The story is Beyonce’s cathartic journey from denial into anger, through apathy and emptiness, and eventually to a place where she can confront her unfaithful husband about his actions, forgive him, rebuild their relationship, and continue together into the future. The magic of this odyssey is in the extraordinary splendor of the film’s emotional palette. It’s not just how much feeling Lemonade has, but how intelligently Beyonce takes her normal persona of an unflappably confident and empowered woman and sends it into Hades and back out again. Lemonade has the effect of deepening Beyonce’s past work, of making us see her with new eyes. What once may have played simply, if entertainingly, as diva swagger now takes on a new meaning. That swagger is her shield as she traverses the battlefield. After years of cutting down weak foes, in the form of insensitive lotharios and jealous female competitors, Beyonce finally finds a worthy adversary. Not in an unfaithful Jay-Z, but in her own conflicted feelings of self-worth.

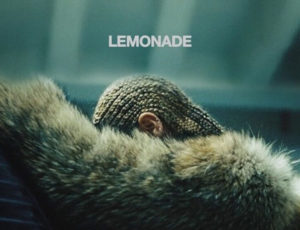

I have thus far described the skeleton of the plot, but the real beauty and thrill of Lemonade is in seeing these twelve unspeakably dynamic music videos. If it were nothing else, Lemonade would be twelve of the very best music videos ever made. Each one of them would more than merit a Kanye West interruption. In one of the first videos, for the song “Hold Up”, Beyonce boldly breaks free of her own denial, pushing open the great doors of a city hall and striding into the daylight with a torrent of water rushing around her feet. Clad in a bright yellow dress and carrying a baseball bat, she swings with uncontrollable glee at car windows, fire hydrants, closed circuit security cameras, and, in a great humorous touch, a piñata. Those images of Beyonce, resplendent in her mustard-colored gown, delightedly dispensing destruction and laying waste to all the bullshit behind her are iconic by now. But, in truth, almost every frame of Lemonade felt iconic the moment I laid eyes on it. This is true of the images, and is also true of its biting, brokenhearted wit. If there is any doubt about how influential Lemonade already is, I recently saw “Call Becky with the good hair” emblazoned across a Finding Dory t-shirt. The video for “Don’t Hurt Yourself” contains the famous album cover shot of Beyonce, head down and wrapped in a thick fur coat, leaning against her luxury car and just seconds away from completely giving herself over to rage. When she starts singing, her voice sounds like gravel and gasoline and she stalks the retreating camera like a vindictive hyena. If anything this year sounded more like great, pissed off rock and roll than “Don’t Hurt Yourself”, I will be kindly surprised. At the end of it, she flings her wedding ring at the camera and the film adds another iconic image to its growing list of them. The great shots within these sixty-five minutes are too numerous to fully recount, and they are all striking and symbolic and loaded with emotion. Beyonce burns a bedroom and the fire spreads to the whole house. She dances on the hood of a prison bus with an upraised middle finger. She dances around in the old tunnel of a ruined Louisiana fort while a silhouette resembling her estranged father plays steel guitar. Lemonade works because Beyonce Knowles is an artist who understands the sneaky poetry of the meme. Like Bob Dylan, she knows there are lot of good ways to hurt a mean lover, but most of the best ones tend to just be a short, tossed off sentence. “You try this shit again, you gon’ lose your wife,” she whoops with a deranged sense of liberation.

Lemonade breathes fire for about half of its running time, but it eventually finds a gentler spirit and emerges as one of the most poignant, overpowering films about forgiveness ever made. And, I would argue these later moments are so unbelievably moving precisely because we have been to the absolute depths of despair first. In the later scenes, Lemonade is still wise and frank about relationships and the havoc adultery can cause, but Beyonce has conquered the hurt and the film no longer howls as wildly. She wants her wayward man to think constructively about why he would betray the love of his life and his love for himself. In an angrier moment she yelps, “When you play me, you play yourself!” But now that the red smoke has cleared, the wisdom of that statement still stands. For all the startling, aggressive power of Lemonade’s early scenes, the second half is just as vivid for its vulnerable beauty. As Beyonce imagines forgiveness as a kind of baptism, she and a line of black women in white robes wade out into the middle of a large bayou with an enormous sky above them. Standing in the light of dusk, they face the horizon and raise their hands above their heads. The next video begins and, suddenly, Jay-Z is there in front of us. He doesn’t appear all at once, but gradually. As Beyonce sits in her home, playing her keyboard and plaintively singing about promises, we see a man’s wristwatch sitting on a table. Then we see a hand with a wedding ring upon it reaching across a pillow. Then the top of the man’s head appears. Finally, his entire upper body can be seen in silhouette. This segment is beautifully directed, and it gets forgiveness just right. After such a tremendous breaking of trust, forgiveness can only happen as a painstaking process. You can come to see the other person as who they were again, but surely it is not easy or swift. If you are lucky, they return to you in pieces and parts, until one day they stand whole before you. The slow emergence of the sinner into the story of the betrayed, or more specifically her decision to include him, makes Lemonade a tremendously rewarding story of choosing to forgive. “So we’re going to heal,” Beyonce says softly. She walks above the old ruins and tunnels that once surrounded and swallowed her, and the joyful, reggae-tinted strains of “All Night” play. This bouncy song is about looking forward to kissing and holding the person you love after learning to let them back in your heart. And here I will confess that I teared up. R&B history has no shortage of songs about wanting to kiss and hug and make love to someone. Some are good, some are bad, some are “Too Close”. But none have ever moved me the way this one did. The context of the hard road that had come before made it overwhelming. Beyonce was basking in the simple joy of recapturing a love that had been in jeopardy. She had turned a medium-paced funk jam about make-up sex into blissful, euphoric poetry, and I could not help but weep with joy about it.

And, when I put it all that way, Lemonade really is the kind of personal story that just about anyone can relate to. It is obviously particularly relatable to anyone who has been cheated on or cheated on someone, or to anyone who has been through the sometimes painful process of learning to grow or change with a romantic partner. And even if none of that applies to you, chances are still good that you have had a hard experience with forgiving another person. So, with all that being so, does one need to believe in the existence of racial injustice to be moved by Lemonade? No, I suppose not. Still, that perspective is crucial to understanding where Lemonade is really coming from and for feeling the full weight of its mighty catharsis. The struggles of being a black person, and a black woman in particular, is a vital part of the film’s iconography, from its decision to set itself entirely in New Orleans to the aforementioned line about Becky and her good hair, which references both the difficulty black people experience in finding barbers who can handle their hair consistency and the troubling idea of black men dating white women as a sign of upward mobility. How many people reading remember that O.J. Simpson left his black wife to marry Nicole Brown Simpson? Before laying into Jay-Z on “Don’t Hurt Yourself”, Beyonce pauses to insert a montage of black female faces, underscored by Malcolm X’s famous remark that the black woman is the most disrespected person in America. Many of the film’s scenes play out at an old plantation house with black women wearing Antebellum-era white dresses. And, as Beyonce starts to forgive Jay-Z, she starts looking at him in the context of his own black identity. A series of mothers hold up pictures of sons who were lost to police brutality, and an actress holds up a photo of a fallen slave because he is also a part of this pattern. Beyonce seems to say to her husband, “You have done wrong, but do we not both face bigger threats than one another?” To view Lemonade as simply a story of forgiving infidelity, without taking Beyonce and Jay-Z’s race into account, would be to pretend that race can ever not be a part of the context. And I will now officially cease mincing words and say that of course it is. It always is.

But, if there were any doubts that racial injustice and the experience of being black in America are pivotal parts of Lemonade’s message, the final music video, “Formation”, swoops in after the final credits and slaps them down to the cement. The major story of the film is complete, with Beyonce and Jay-Z reunited and happy. There is no more spousal infidelity to forgive, but here we are. We must be here to talk about someone else. “Formation” is a furious, percussive dance song with all the militaristic swagger its name promises. It is about Beyonce’s roots as a black woman with ties to Louisiana, the land where the levees broke. The song is a call to unify, organize, and form ranks. Its beat pulses and seethes and it is clear we are back in a place of anger. Despite the odd reference to rewarding a sexual partner with seafood dinners, “Formation” is about protest and defiance against any oppressive force. We have watched Beyonce forge a path to forgiveness with her husband. Now that she has the one act of reconciliation behind her, she’s here to start the process again with a different transgressor: society. Over the last hour, we have seen that forgiveness is possible. But,the last image we have is of Beyonce sinking into the Katrina floodwaters on the roof of a police car. The film cuts to black and our penance remains out of reach, somewhere below the flood. There can be no forgiveness until there is an apology.